Friday, February 3, 2017

An 1889 U.S. Supreme Court case sets precedent for Trump's immigration order

Exactly one week after President Donald Trump signed an executive order restricting entry into the United States based on religion and national origin, a federal judge in Seattle will hear arguments on a temporary restraining order to suspend its effects. The restraining order was filed by Washington state Attorney General Bob Ferguson, along with a lawsuit seeking to have provisions of the order declared unconstitutional.

As U.S. District Court Judge James Robart hears arguments today, the precedent dates back to a U.S. Supreme Court case from 1889.

"It's been a long while since we've tried to exclude people based on what we would consider a protected class — be it race, national origin, religion or gender," says Jason Gillmer, a professor at Gonzaga University School of Law who studies constitutional and immigration law. "So these old cases that date to the 1880s and 1890s have never been overturned [by the court]. Really since World War II, we haven't been a country in the business of excluding people based on protected classes."

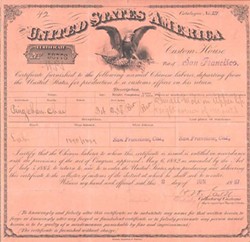

Chae Chan Ping arrived in San Francisco in 1875. He lived and worked there for 12 years, until, in 1887, he boarded a ship for China, his home. Ping carried with him a certificate that ensured his safe return to California.

In 1888, he was denied entry back into the U.S. and was detained on the steamship that carried him from Hong Kong. His case — known as the Chinese Exclusion Case — and others, reached the United States Supreme Court.

Ping first arrived in the United States after a treaty between the U.S. and China established a friendly relationship and encouraged immigration.

One section of the agreement highlighted the "inherent and inalienable right of a man to change his home and allegiance, and also the mutual advantage of free migration."

During Ping's time in the U.S., however, Americans began to change their minds and chipped away at the flow of Chinese immigrants coming into the country. With the U.S. facing economic depression, Congress moved to restrict Chinese immigration specifically, despite the fact that economic woes had nothing to do with Chinese workers. Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, which suspended Chinese immigration for 10 years.

Just days before Ping's re-arrival in San Francisco in 1888, an amendment to the Exclusion Act took effect. It said that even those Chinese who entered the country

Ping was detained on the"The differences in race added greatly to the difficulties of the situation. ... They remained strangers in the land, residing apart by themselves and adhering to the customs and usages of their own country. It seemed impossible for them to assimilate with our people or to make any change in their habits or modes of living."

tweet this

Eventually, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to review it. The court ruled that Congress had the right to enact laws even if they conflicted with treaties and international law. Additionally, Justice Stephen Johnson Field wrote that the courts could not interfere with congressional and executive action on immigration. It was the other two branches of government — executive and legislative — that were responsible for national security, territorial

"If therefore, the government of the United States ... considers the presence of foreigners of a different race in this country, who will not assimilate with us, to be dangerous to its peace and security, ... its determination is conclusive upon the judiciary."

In other words, the judge's opinion rings true to the philosophy exclaimed by our commander in chief during his inauguration: "America First." Congress and the president, Justice Field opined in 1889, know best when it comes to immigration.

Within a week of taking office, Trump signed an executive order that temporarily bans all refugees from entering the U.S. and indefinitely bans Syrian refugees. It also temporarily bars immigrants coming into the country from seven Muslim-majority countries.

Ferguson, Washington state's attorney general, filed a lawsuit within five days.

So far, Washington-based corporations Amazon and Expedia, along with Washington State University, the University of Washington, the Department of Revenue, the Department of Social and Health Services and the Washington State Board for Community and Technical Colleges have filed declarations in support of the attorney general's suit.

Ferguson has also filed a temporary restraining order, which will be heard in court this Friday. And Trump is named in at least 50 other federal lawsuits across the country.

A lot has happened since the last time the United States courts weighed in on attempts to prevent people from coming into the country based on a specific class such as race or religion.

A young poet's words — "give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to be free" — were inscribed at the base of the Statue of Liberty in 1903. The U.S. fought in two world wars. More than 100,000

A major civil rights movement brought the passage of important legislation (Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act, for example). Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated. Bans on interracial marriage were ruled unconstitutional. Congress passed a law authorizing a

And a whole host of government actions ensured basic rights to people of varying abilities, sexual orientations, religions and national origins. The American sentiment toward "others" lurched toward acceptance and

For Gillmer, the GU law professor, the question will be whether today's courts are willing to give as much deference to a co-equal branch of government as the Supreme Court did more than 100 years ago.

Below are excerpts of Justice Field's opinion, illustrating the court's attitude toward "others" at the time:

"These laborers readily secured employment, and, as domestic servants, and in various kinds of outdoor work, proved to be exceedingly useful. For some years little opposition was made to them except when they sought to work in the mines, but, as their numbers increased, they began to engage in various mechanical pursuits and trades, and thus came in competition with our artisans and mechanics, as well as our laborers in the field. The competition steadily increased as the laborers came in crowds. ... They were generally industrious and frugal. Not being accompanied by families except in rare instances, their expenses were small and they were content with the simplest fare, such as would not suffice for our laborers and artisans."

"The differences in race added greatly to the difficulties of the situation. ... They remained strangers in the land, residing apart by themselves and adhering to the customs and usages of their own country. It seemed impossible for them to assimilate with our people or to make any change in their habits or modes of living.

"As they grew in numbers each year, the people of the coast saw, or believed they saw, in the facility of immigration and in the crowded millions of China, where population presses upon the means of subsistence, great danger that at no distant day that portion of our country would be overrun by them unless prompt action was taken to restrict their immigration. The people there accordingly petitioned earnestly for protective legislation."

"Those laborers are not citizens of the United States; they are aliens. That the government of the United States, through the action of the legislative department, can exclude aliens from its territory is a proposition which we do not think open to controversy. Jurisdiction over its own territory to that extent is an incident of every independent nation. It is a part of its independence."

Tags: Bob Ferguson , Jason Gillmer , Gonzaga School of Law , Donald Trump , The Chinese Exclusion , U.S. Supreme Court , News , Image