On a family farm in the 11-person town of Dusty, Wash., Phil Appel runs another experiment.

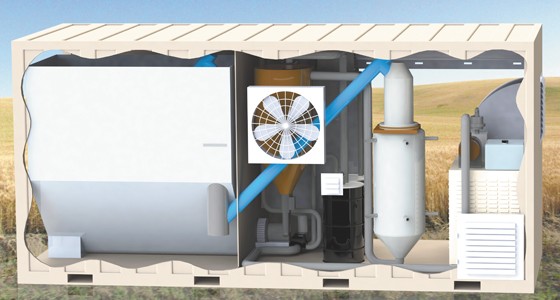

A tractor dumps straw into a jury-rigged jumble of pipes, boards and insulation fiber. A box fan — the sort that’s $19.98 at Wal-Mart — is strapped to the machine with blue painter’s tape. The contraption is built on a shoestring budget and has been rearranged into a half-dozen configurations. Sometimes, that’s how inventing works.

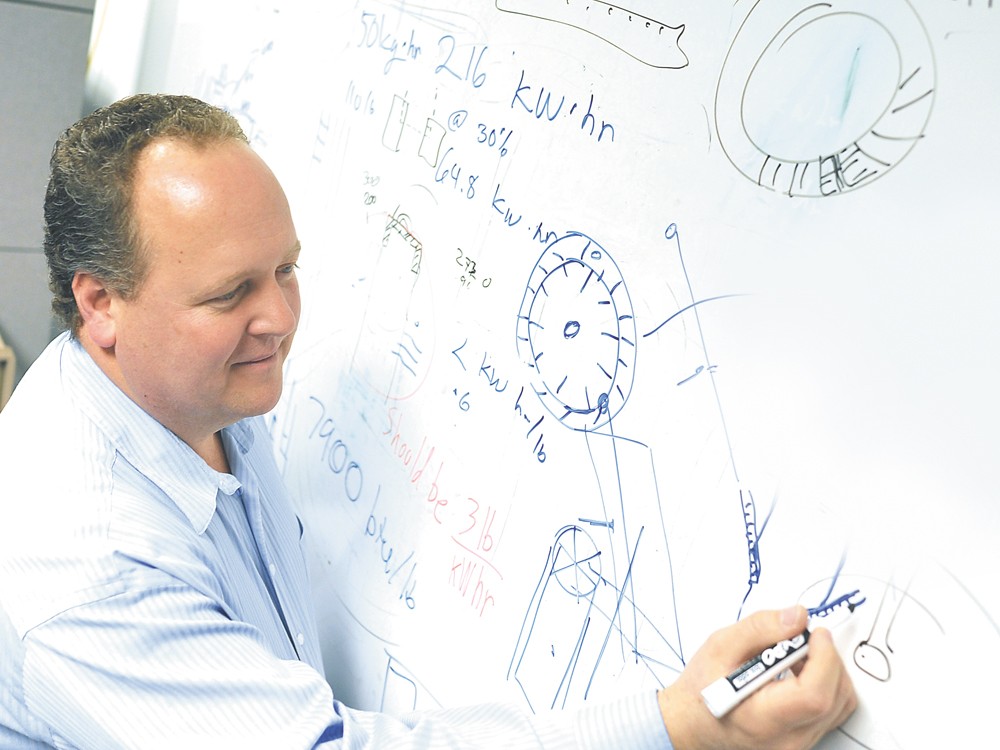

Appel, round-faced with glasses, has devoted his retirement money and the last few years of his life to a single idea. That idea, with his startup company AgEnergy, could transform agriculture around the globe.

“You start here,” Appel says, tossing a zip-close bag of straw onto his office desk. “And you see what it produces.”

Each square foot of a modern wheat field, thanks to genetic engineering, produces four times more than it did a century ago. More wheat, though, means more leftover straw. But Appel figured the straw didn’t have to go to waste. He watches the History Channel and recalls how Nazis turned organic material into liquid fuel for Panzer tanks in World War II.

The 47-year-old former mechanical engineering professor previously worked on electric cars and lead batteries, engineered liquid-cooling systems and designed windmill generators out of 55-gallon drums. But before all that, he was a farm kid. He grew up with nine siblings east of Pullman and worked in the fields all the way through grad school.

Now, he’s developed a complex computer model that can determine, farm by farm, how much money could be saved by his invention, which powers a generator by burning straw. “We’ve got investors out in the Tri-Cities area who are paying $30,000 a month for electricity,” Appel says.

Of all the places Appel could have planted his business, he chose Spokane and, in doing so, he joins a small but devoted group of startups looking to change the face of innovation in the Inland Northwest.

There is reason for skepticism. The region has never fully realized its high-tech dreams, thwarted in part by a lack of venture capital and, perhaps, by what many describe as a risk-averse culture. But there is also reason for hope: Success attracts more success, and the region’s game-changing idea may have already been discovered.

THE BAD NEWS

“When it comes to our region, what if we dared to dream?”

That’s how a report commissioned by the nonprofit Inland Northwest Technology Education Center, titled “Developing an Innovation Economy,” began back in 2003. “To dream of world-class industries, high-growth companies, and wildly successful entrepreneurs.”

Before concluding that Spokane could successfully spur innovation, the report examines the status quo — with the region lagging behind Boise, lacking investment money and hobbled by bickering. It also notes the area’s reputation as “the poster child of unmet expectations, unrealized potential, and unrelenting mediocrity.”

“In spite of an impressive asset base and a deep pool of talent, our economy has produced scant growth in recent years,” the report states.

Spokane has several advantages, with affordable housing, cheap electricity, thriving universities and advanced fiber-optic networks. In 2004, a year after the report was issued, Time magazine gushed over Spokane, calling it “a live-in laboratory where city-employed nerds are crash-testing the wireless technotopia of the future.”

Time focused on a local company, Vivato, which had covered much of downtown under a single wireless hotspot. But little more than a year after the article, Vivato was liquidated by its investors, a victim of manufacturing difficulties and competitors promising to do more for less.

Far from being a “technotopia of the future,” the information sector last year was a smaller part of Spokane’s economy than at any point in the past 15 years, according to the Community Indicators Initiative of Spokane. Since 2000, the number of patents per person has grown two-and-a-half times as slowly in Spokane as the state average.

Far from having an explosion of startups, last year fewer businesses started in the city of Spokane than any year since 2003, records show. And far from rapidly adding high-wage jobs, Spokane still pays some of the state’s lowest wages.

So while the region has added about 2,000 professional/technical jobs in the past 12 months, layoffs at three big tech firms — Itronix, Getronics and Agilent — cost about 1,500 positions since the Great Recession.

“We’re in a much more serious crisis right now,” says Chris Kelly, former chairman of the Entrepreneurs Forum of the Great Northwest. “We went from being close to the national average to being way below it.”

Spotlights on local innovations flickered off. The Terabyte Triangle — a newsletter and website extolling technology companies in downtown Spokane — closed down after 14 years in 2010. And in 2012, for the first time in 15 years, the Catalyst Awards weren’t held to reward innovation in the region.

“Overcoming our negativity is our biggest obstacle,” according to one survey response included in the 2003 study. “We need to stop bad-mouthing our city and be proud of what we have.”

While there are plenty of obstacles, a walk around the University District, on the eastern edge of downtown Spokane, reveals a more encouraging vision for the future.

CRITICAL MASS

Spokane’s best shot at amassing a creative concentration starts in the University District, one place drastically different than it was a decade ago. Now there’s the Riverpoint Academy, where high school students study math, science and technology. Now there’s WSU Spokane’s Applied Science Laboratory, where a chemist has partnered with Boeing to invent the next generation of airplane coating.

And before long there will be WSU’s Biomedical and Health Sciences building, which will include dozens of new laboratories, classrooms and researchers, and generate an economic impact that is expected to rival Fairchild Air Force Base.

Gary Pollack, dean of the College of Pharmacy, predicts it will supercharge local innovation. “I’m guessing, by 2020, we’ll have 300 new scientists in Spokane,” he says, adding that those scientists will spin off new biotech companies, based on brand-new research, drugs and equipment.

“I like to think about what’s happening in Spokane is kind of like what happened in the Research Park triangle area in North Carolina,” Pollack says. In the early 1960s, he says, the community of Durham, N.C., intentionally shifted its tobacco economy toward biomedical research. It worked remarkably well. He sees Spokane making the same sort of city-wide commitment.

A few hundred feet from the Riverpoint campus, across from the Gonzaga baseball field, investor Tom Simpson walks through the newly constructed McKinstry Innovation Center. The Innovation Center is the opposite of a cubicle farm, featuring wide-open atriums, shared conference rooms, a wine bar and a workout facility.

“This building will be the hub for innovation in Spokane, hands-down,” Simpson says.

McKinstry, a company that designs, constructs and operates buildings, made the Innovation Center into its Spokane headquarters. Modeling after its success in Seattle, McKinstry decided to rent half of its space to local innovators, figuring that when creative companies share the same space, they all thrive: bouncing ideas off each other, sparking epiphanies in the hallways, drawing on each other’s skills.

In sprawling open space, the young entrepreneurs at GreenCupboards — an online merchant that lets shoppers filter goods by categories like “carbon neutral” — huddle around computers, filling orders and searching for new eco-friendly products to sell.

In another office, a developer runs a business that attaches video messages — via QR codes — to floral arrangements. Up the stairs, scientist Lisa Shaffer fine-tunes the tests her company, Paw Print Genetics, will use to check dogs for genetic diseases.

For local startups, Simpson may be the most important guy to talk to. He’s helped fund companies like GreenCupboards and Gemiini, an online educational service teaching autistic children language skills. A few weeks ago, the former investment banker announced he’d organized another $550,000 round of investment in regional companies.

In his office in the Innovation Center, beside the box of organic BumbleBars and his framed Ironman race numbers — he’s done five — Simpson points to his backgammon board.

“You can play backgammon very safely, and you might just do OK, but you may not have a whole lot of fun. Or you can make a lot of risky moves,” Simpson says. “I like to make risky moves.”

Simpson is now the head of the Spokane Angel Alliance, a local group of more than 90 “angel investors” that includes City Councilman Steve Salvatori. Angel investors usually invest smaller amounts of money than venture firms, and in younger companies. Mature companies can find investors worldwide, but young ones almost always have to start locally.

Catherine Greer, executive director of Connect Northwest, a nonprofit that links the Angel Alliance with startups, is working to recruit more investors. Last year, she helped bring an additional 20 to the Alliance. Their names remain secret. Many, she says, don’t want to be swarmed with requests to fund this or donate to that. “The whole process is very discreet,” Greer says.

But even as the ranks of the Angel Alliance swell, entrepreneurs still think Spokane needs more choices. Since the beginning of the Great Recession, banks have been less willing to lend, and investors less willing to take risk. Plus, the Business Development Corporation of Eastern Washington, which partnered with Sirti to loan money to startups, folded.

“A lot of the money is held by an agricultural base and mining base,” says Norm Leatha, entrepreneur in residence at Gonzaga University. “They’re used to a much more conservative investment.”

Chris Kelly, of the Entrepreneurs Forum, points to the limited number of local investors as a major obstacle to innovation: “If Tom Simpson doesn’t understand your idea or doesn’t want to invest, who do you go to?”

REGROUPING

Just a few hundred yards away from the Innovation Center are the offices of Innovate Washington, formerly Sirti. The change from Sirti to Innovate Washington has been controversial in the entrepreneurial community.

“Right now, I am scratching my head and wondering what the strategic direction is,” Simpson says.

Sirti, a state agency known for loaning money to Spokane startups, had advised businesses on plans and market strategy, and connected them with free legal services. As an “accelerator” for startups like Signature Genomics and Pacinian, a remarkable two-thirds of its clients survived.

But in the fall of 2010, Sirti merged with the Washington Technology Center, a statewide economic development agency focused on innovation. The resulting entity, Innovate Washington, focuses almost exclusively on the clean energy sector, and plans to begin helping established businesses, instead of just startups.

“It’s an entirely different business model,” says Innovate CEO Kim Zentz. “It’s a model of a different scale.” Zentz pushed for the change. By combining organizations and going statewide, she hopes, Innovate will win bigger grants and have a bigger impact using the same resources.

Two-thirds of Sirti’s employees left as it morphed into Innovate. Michael Urso, formerly the senior principal consultant at Sirti, says the turnover came from frustration over leadership and the new direction.

“The program we built that was so successful is now just a shell of itself,” Urso says. “You talk to the clients, they’re not overly happy.”

Today, Innovate Washington works with less than a third of the number of startups in Spokane as Sirti did. “We’re focusing our efforts on a fewer number of clients and a deeper engagement,” Zentz explains.

Nevertheless, it’s here that Appel keeps an office as he looks for investors to back his straw-fueled generator. He’s aware of all the politics surrounding Innovate Washington and has had a front-row seat to witness the difficulties in the transition. But the community is small, he says, and in all aspects of Spokane’s innovation environment, he’s very careful to avoid saying anything that would offend anybody, especially potential investors.

After all, he’s raised some money, but not yet enough to build his first production unit. “People are not great risk-takers in Spokane,” he says.

When Simpson passed on funding his company, Appel went to one of the only other major investment groups in the region, the recently formed Inland TechStart Fund.

For some startups, neither option is ideal. Simpson often writes his terms so that if the company is liquidated, he gets all his money back before the company owners get a dime. And the Inland TechStart Fund usually gets an advisory board seat with a relatively small investment, which can turn off larger investors in the future.

Fortunately, other options are appearing. The Spokane chapter of the Keiretsu Forum, a group matching national investors with startups, started three months ago. Come January, Appel will use video-conferencing technology to make a presentation in front of hundreds of investors nationwide.

Appel will have only one shot. But he’s confident. Farmers could use the extra energy he could help them generate. A single irrigation pivot sprinkler, he says, sucks up 60 times the power of an average household. The United States has 125,000 of those sprinklers.

“Will we have room to expand?” Appel says. “We will have room to expand across the United States, across the world.”

THE BIG HIT

The problem in Spokane isn’t necessarily that new startups fail. “Our percentage isn’t worse than anywhere else. Our percentage is probably better,” says Norm Leatha, entrepreneur in residence at Gonzaga University. “But we haven’t had a wild success.” A few local startups became successful enough to sell to larger companies, but they weren’t insane, city-changing successes.

Above a fitness center in Liberty Lake is a company that Simpson says has that potential.

“Let’s use the word ‘revolutionary,” Simpson says. “You’ll wave your cell phone and things come alive.”

Gravity Jack CEO Luke Richey, with a blond goatee and blue jeans held up with a Star Wars belt, scrawls his vision for the future on the conference room whiteboard. “That will be 2014 — you’ll see medical applications for augmented reality,” Richey says. “[In] 2016, there will be a trend of putting on goggles and interacting with computers without ever having a screen. That’s my belief.”

Granted, he admits his optimism occasionally outpaces reality. But even now, in 2012, Gravity Jack’s written a software engine that can not only search the real world — recognizing real-life objects with a smartphone — it can lay a three-dimensional image or video on top of it.

They can embed almost any visual sight with information: A movie poster turns into a movie trailer; a magazine photo transforms to a behind-the-scenes video; a Coca-Cola can becomes a Coke commercial.

“I’ve got a group of scientists back here, not just software developers,” Richey says. “These guys literally dream in math.”

The company’s 25-year-old chief operating officer shows how, seen through an iPad camera, a printed-out page transforms into a cutesy three-dimensional game board. With a swipe of his finger, a tiny blue round raccoon character goes careening — with a falsetto “wahooooo”— over a computer-generated brick wall to hit a target on the other side. He moves the iPad to a different vantage point, and the virtual-reality game-board rotates as if it were really there.

“Get ready for MushABelly AR!” a hyperactive announcer voice says in a commercial airing on Nickelodeon. “That’s augmented reality! And it brings the game to life in your world!”

Richey says Gravity Jack built the only augmented-reality engine in the United States. For now, that’s meant marketing gimmicks and mobile games like MushABellies. But their ambitions go further: Their technology can “virtualize” printer repair by demonstrating step-by-step repairs on a 3D model projected on the actual printer. It could change everything from engine repair to recognizing bomb circuitry.

“The Department of Defense has set aside $8.3 billion for augmented reality in 2013,” Richey says. “We’re writing the white paper right now.” The Department of Defense wants Gravity Jack to identify how their computer-vision could impact everything from jets and soldiers to mechanics repairing tank treads.

“We’re growing like crazy,” Richey says. “We keep adding employees every year.”

If Gravity Jack is bought at a high price, the impact could be seismic. When local investors multiply their money, they often spend it on yet another startup, maybe this time something even bigger. City Councilman Steve Salvatori invested in local thin-keyboard manufacturer Pacinian, and when that sold, he says, he turned right around and plugged that money into Simpson’s new investment fund.

Success powers-up a business’s founder with new clout. Lisa Shaffer started a biotech company called Signature Genomics that revolutionized testing for genetic diseases. Her company sold for $90 million, and when she wanted to start Paw Print Genetics, she says she carried newfound credibility when looking for investors.

And if those tech companies get large enough, they can spawn whole new innovative business. Some of Spokane’s biggest tech companies came, not from startups, but from the Avista Corporation. Avista spawned fuel-cell manufacturer ReliOn and global smart-meter company Itron, and that company, in turn, spun-off rugged-laptop manufacturer Itronix. In Boise, for example, innovation continues to be spurred by its two massive tech companies, Micron and Hewlett Packard.

Even the struggling arts in Spokane would be aided by a big hit, Kelly says, which would attract more investors. “If we create a successful company, then maybe we have a hundred more people who can go to the symphony,” Kelly says. “We have the opportunity to create a virtuous circle, where we start spiraling upwards.”

WEEKEND WARRIORS

Website developer Dan Gayle stands before 100 people in a Gonzaga University lecture hall, knowing that he only has one minute to make his pitch.

But for 20 seconds, he doesn’t make a sound. He just dances, shaking his butt, pumping his arms, with only nervous laughter and whoops from the audience as a soundtrack.

“I don’t dance. I’m not a dancer,” Gayle says. “I just let myself go free, swinging my arms around like what I think dancing looks like.”

Gayle is awkwardly dancing as part of his pitch at Startup Weekend. Startup Weekends are global phenomena that began in Seattle: engineers, marketers, designers and business experts gather together, pitch ideas, form into teams, and then have 54 hours to turn all that into an actual product.

Gayle’s idea, Busta Booty — an app that would use the iPhone’s internal sensors to track how much you’re dancing — was voted best overall at the September Startup Weekend event.

Gayle is 31, but most of his team was far younger. “I had all the young people, high school students, college students, and we were competing against professional business people,” Gayle says. “And I won. I kicked their butts.” And the job offers, he says, streamed in.

Only two have happened in Spokane so far, but Startup Weekend is inspiring the next generation of entrepreneurs.

After a few teachers noticed that 17-year-old Emerson Shaffer showed up on a snow day for his computer programming club, they suggested he come to the first Startup Weekend. Emerson came up with Pixel Buddy, a modern interactive pet simulator, and came away with an award for best development work. Today, a private investor has given him $100,000 to get his business started. (His mother, it turns out, is Lisa Shaffer, the founder of Paw Print Genetics.)

Next month, on Dec. 15, Connor Simpson, 22, is launching his first startup: Barter’s Closet, an online vendor that lets shoppers buy, sell and trade sell clothing, won first place for interface and design at Startup Weekend this spring. Connor is the son of Tom Simpson. (And yes, his dad is investing.)

Startup Weekend didn’t exist in Spokane before this year. Neither did the McKinstry Innovation Center, or the Riverpoint Academy or the Spokane chapter of the Keiretsu Forum. Spokane voters rejected funding for a science center in 1995, but after years of private fundraising, Mobius opened this fall. And Launch Spokane, intending to connect startup companies with experienced mentors, started up in September.

That’s why Simpson sees momentum. He sees at least 10 different things in Spokane that didn’t exist a decade ago. Besides the fledgling startups, there is the Tango electric vehicle that has caught the eye of some celebrities, and FlyBack Energy, which has figured out how to save massive amounts of energy by dimming giant outdoor lights.

Of course, Spokane had momentum before, but it never sprouted into full-scale change. It’s possible that Connor and Emerson’s startups might fail, that Appel might not find the investment he needs and that the hopes of McKinstry and Innovate Washington go unfulfilled.

But accepting that possibility is what Simpson is talking about: Spokane, he says, needs to figure out its economic identity. Does it want to continue to eke along, safely and glacially? Or does it want to go for big leaps that, yes, may end in belly-flops?

“Whenever there’s a failure [in Spokane], it’s just a glowing black mark,” Simpson says. “Frankly, in my world, entrepreneurs embrace failure.”