It's different, now, in the offices of the Northwest Museum of Arts & Culture. “It’s quieter — literally,” says Ben Mitchell, senior curator of art. Speaking by phone, he says, “The largest change I experience is fewer people to talk to. I hear all these voices behind you. You don’t hear anything behind me right now.”

That’s because, in the past year, there has been a 50 percent turnover in museum staff. Since June, around 13 full-time-equivalent positions have been eliminated.

Four more resigned, and only one of those positions has been rehired. One resignation came because, with all the layoffs, the workload was just too much. “It’s hard for people to have six things to think about instead of two or three,” Museum Services Manager Lori Bertis says.

Like many museums across the country, holes were blasted in the MAC’s revenue streams when the economy imploded. Fifty percent of the museum’s money comes from the state, and the state slashed its budget hard. The MAC found itself with, essentially, $775,000 less in operating revenue.

For now, the budget is balanced, a task accomplished by cutting employees, by reducing the number of operating days, by slicing pay, by stretching out exhibits, by using volunteer fundraisers. But expenses are bound to increase again, and new State budget cuts are bound to arise. And this year, there’s no government stimulus to help out.

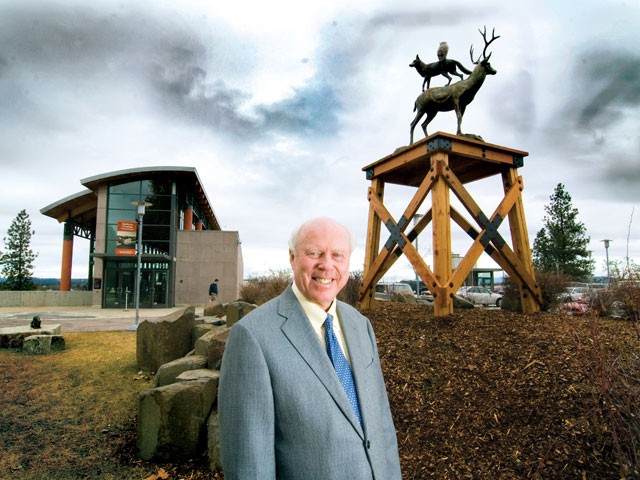

CHOICES | Ron Rector, the recently minted executive director of the MAC, preaches confidence. A former marketing manager at IBM, Rector speaks the dialect of business. Exhibits and programs are “products.” Visitors are “customers.”

“I also ran a pellet factory,” Rector says. “The management issues stay the same. The products change.”

Rector was a departure from the previous CEO of the MAC, former Spokane mayor Dennis Hession, says laid-off former chief development officer Lorna Walsh. Hession wanted to cut programs to save staff; Rector cut staff and overhead to save core programs.

“Ron approached things from a corporate-business-fiscal model,” Walsh says. “That is a hard thing to overlay on an organization with cultural, artistic and ephemeral pieces.”

Like any business, Rector explains, the profits and losses are important. But not just the profits and losses. He breaks down his rubric of success into four presentation-ready bullet points: 1) Financial health, 2) Customer satisfaction, 3) Employee development, 4) Internal processes.

The message about the MAC he’s sending is far from dire. “We’re excited about the place,” Rector says. “That’s how I want it to read.”

FATIGUE | The staffers at the MAC lament their lack of resources. But they’re used to that.

The re-imagined MAC opened in November 2001 — a time when the stock market was falling, when uncertainty reigned, when money poured into the Red Cross instead of into museums.

“It is exhausting that for the last six years, it’s been a little cut there, a little change here — this has been an atmosphere of always taking on a little more,” says Michael Holloman, director of Plateau Studies. “Always saying ‘yes’ one more time… It’s exhausting.”

From her friends still at the museum, Walsh says she’s hearing “stress” from employees required to do more and more roles. Turns out there’s a problem with wearing so many different hats for so long: Eventually, it begins to strain the neck. “There’s a point where you can’t do more with less,” Walsh says.

SOLUTIONS | “Big corporations that were downsized — they’ve come out of it better for it,” Rector says. “For years, IBM was just a hardware company. Today, 65 percent of IBM revenue’s comes from consultation.”

They’re been refined by the fire, MAC workers say.

They’re stronger, more focused, more efficient. “We’ve had to be pretty damn creative or we wouldn’t be here,” says Mitchell, the art curator. “Imagine if you guys tried to put out a paper with half your staff — you have to make interesting creative decisions, or you’re not going to publish.”

To help brainstorm just those types of decisions, Rector has created an advisory board of downtown business leaders.

Despite world economic calamity, local donations are up 25 percent. With Walsh gone, half of the fundraising is done by volunteers. The Clark Company donates public relations work.

Hopefully, Rector says, the MAC’s “Works from the Heart” auction, will bring in at least $20,000. (Last year, Walsh says, they raised about $14,000.)

Thanks to their new liquor license, the second Friday of every month, the MAC throws an after-work cocktail party called “BeGin.” The event itself breaks even on cost — but it’s another way of drumming up members.

Rector floats more theoretical ideas: Digitalize the museum archives, and put the full articles behind a Spokesman- Review-style pay wall. The lost jobs mean a surplus of empty space — perhaps, he suggests, the museum could rent out some of its empty offices.

DEEPER CUTS | In July, when the new fiscal year arrives, the new cuts will begin. Twice this year, Rector has flown over to Olympia to tell the MAC’s story. He met with nearly every Eastern Washington state representative and senator. But others are doing the same thing: public schools and colleges and charities and social workers and cities, all lamenting their beleaguered budgets.

If the governor’s recommendation for next year’s budget stands, the MAC will have to weather another $145,000 blow to its annual budget — equal to the salaries of roughly three staff members.

“We’re kind of at rock bottom,” Rector says. “To be truthful, I don’t know what I’d cut.”

Rector says he won’t cut more staff. But what else? “At some point, you just become a repository for stuff. You lose that public face,” Walsh says. “I’m not sure exactly where that point is, but I would say they’re pretty close to it.”

Even if the state stops giving money entirely, Rector says, “I see no reason why the MAC would ever go out of business.” He believes that Spokane won’t let the MAC die.

Despite differences of opinion, that resolve links Rector and Walsh and all the museum staff we talked to.

Look into the eyes of the employees working at the MAC today, says Holloman. “That look is one of absolute determination. Are we a little disheveled? Have we taken some hits? Sure…. These are challenging times.”