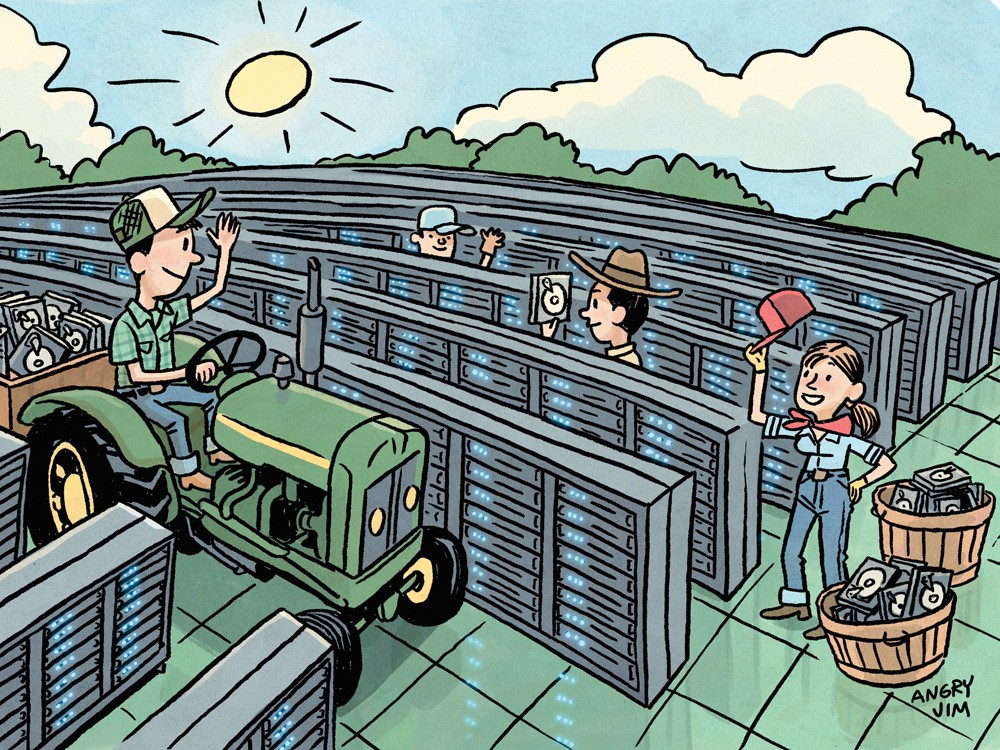

As a teenager, Peter Shelton used to drive past acres of farmland — open fields covered in alfalfa blowing in central Washington’s robust winds.

But now, he drives directly to the fields. And instead of alfalfa, there’s Yahoo!

Shelton, 35, is from the small town of Quincy, Wash. When he went away to college, he didn’t think he’d ever move back home. But he did, and now he has a steady job in one of those fields, where he’s surrounded by hundreds of computer servers, their slim black plastic casings and miles of crisscrossed wires and cables.

“It’s changed my life because I wasn’t planning on living close to my family,” Shelton says. “Now I can have them over for Thanksgiving and Christmas. Without the data centers, that wouldn’t have happened.”

Since 2007, Yahoo!, Microsoft and another company have built data centers in Quincy, 30 miles southeast of Wenatchee. Two more are nearing completion and another just broke ground. (The company building the latter wouldn’t disclose which Internet company will be using it, citing “security concerns.”)

The draw to Quincy is cheap land, cheap “green” power and good connectivity. A substantial fiber optics network makes it easy to have a reliable Internet connection in Quincy, and two main power lines make complete outages almost impossible.

Data centers are the Internet’s central

nervous system, the storage space that every Yahoo! email user and

fantasy football team manager depends on. When people ask Shelton what

he does for a living he tells them, “We build the Internet.” (He adds,

“Anything on the Internet besides Facebook and Google, we do.”)

Yahoo! owns mail, shopping and sports sites, plus the photo-sharing site Flickr. The data centers are full of servers that store the information those sites need to run and the information users store on those sites. But for all the novelty of state-of-the-art information storage in the middle of nowhere, most people in town say it isn’t changing Quincy’s agricultural identity.

“There isn’t a huge difference between a data center and

our apple or potato storage buildings,” says City Administrator Tim

Sneed.

Before the data centers came to town, or even expressed interest, Quincy created a special taxing district, called a port district, to buy land and improve infrastructure, though they weren’t exactly sure what for. It turned out to set the perfect stage for the arrival of the data centers.

Curt Morris, a port district commissioner and realtor, supports the data centers because of the revenue and jobs they bring — what he calls a bargain for the small percentage of Quincy’s total land area they take up.

“They might be 300 acres,” Morris says. “That’s something, granted. But a lot of dry-land farms are 10,000 acres.”

For a town with an economy historically based only on agriculture, the centers promise new jobs, visitors and tax revenue. Street construction, a kids’ recreation program, a new library and a ladder truck for the city’s fire department are all results of Quincy’s newfound income.

Since the first data center broke ground in Quincy four years ago, property tax revenues in the city have increased by $2 million. Though Mayor Jim Hemberry says data centers aren’t responsible for all of that increase, as much as 70 percent — $1.4 million — likely is. Not too shabby for a town of 6,000 people.

About half of the jobs a new data center creates can be filled by locals — heating and air conditioning technicians, electricians, mechanics — but the rest call for experienced computer engineers. Almost all of these professionals are transfers or outside hires, says Jonathan Smith, managing director of the Grant County Economic Development Council.

And for every job a data center creates, more will likely come soon after, to meet the town’s growing population demands, like a new restaurant or a FedEx office.

In a town that was used to seeing an influx of people only when a big act played the Gorge Amphitheatre, the 1,000 construction workers who came to build two data centers in one year did leave their mark.

And as much as property taxes contribute to the town’s well being, retail spending by the workers who come to town to build the centers and the employees who stay to work at them has had an impact. In 2005, before the first data center, Quincy saw $69 million in taxable retail sales. In 2007, the year construction started on Yahoo! and Microsoft, that figure jumped to $476 million, Smith says. Last year taxable retail income was $152 million — higher than before data centers came to Quincy.

“There was definitely a peak,” Smith says of 2007, “but when it comes back down, we’ve got this new normal.”

Those with land that could serve the data centers rarely hesitate, says the port’s Morris. One acre of agricultural land might fetch $5,000 or $6,000. When sold for a data center, the same land can jump up to $40,000.

There is currently as much as $400 million of development happening on the data centers, Morris says.

“For Spokane, that may not be a big deal,” Morris says. “But for Quincy, that’s monstrous.”

The centers, though popular throughout most of town, aren’t without some criticism. Quincy’s former mayor, Patty Martin, who held the office in the mid-’90s, is leading an appeal of air quality permits issued by the state’s Ecology Department to the data centers, citing air pollution emitted by the centers’ backup generators.

Every data center has diesel generators to run the building in case of a power outage. The catch is that the companies also run the generators for tests anywhere between eight and 1,500 hours a month, at least in the case of Microsoft, according to documents Martin received in a public records request.

Like diesel trucks, the generators pump out nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide and other organic compounds, according to a fact sheet released in February by the Washington Department of Ecology’s Air Quality Program. The pollutants have been linked to lung damage, asthma and cancer.

“When Ecology staff review the permit application for a data center, they look very carefully at how much the project will add to the air pollutants in the area,” the sheet reads. “Ecology cannot approve a permit that allows pollutants to be emitted often enough or in high enough levels to cause health problems.”

Representatives from the department, which issues the permits, would not comment on air quality concerns or the data centers in general because the appeals process is ongoing, says Jani Gilbert, an Ecology spokeswoman.

But Martin disagrees, arguing that the emissions are enough to affect the public’s health. She’s pushing for data center companies to use new engines that reduce contamination — whether by the companies’ own will or through tougher city or county regulations.

But Hemberry, the current mayor, says that’s not in the city’s authority, and that he trusts Ecology scientists.

“I feel they did their job and I feel safe,” he says.

Martin sees the data centers as a way for the state and county to make up for budget shortfalls through increased property taxes, and doesn’t think anyone in local government is taking the threats seriously enough.

“In some ways, we’re helping to fill their pockets, but at the expense of our health,” she says.

Martin also alleges that the data centers have caused electricity prices to rise. She claims to have already seen the rate hikes. She argues that the data centers use so much power they are causing the utility district to turn to the energy market — and buying power produced by coal and other polluting methods — to serve the total need.

Not so, says Bonnie Overfield, manager of strategic planning for the Grant County Public Utility District.

“The drive-up in rates is because of the cost to produce power,” she says. “We are making some upgrades to infrastructure.”

Since data centers pay for their own infrastructure and power, they aren’t affecting those rates any more than regular customers, she says.

Additionally, the PUD is allowed to take a percentage of the power produced by the two dams it owns, but that percentage grows when demand does. To serve its current power load, the district is taking 60 percent of the dams’ power. It’s allowed to take up to 90 percent, Overfield says.

The PUD gets most of its power from those dams and has contracts with a local wind project and two smaller hydro projects. The district buys the rest from the energy market.

“On average we sell more power to the market than we buy,”

she says. “But our load peaks during the winter, so we’re always buying

and selling.”

As construction wraps up on Quincy’s fourth and fifth data centers — and the first signs of its sixth one can be seen on the horizon — it’s not clear what lies ahead for Quincy. There are no data centers currently in the permitting process, and Mayor Hemberry is hesitant to speculate about how many more his town is willing to welcome.

On one hand, Quincy probably won’t turn down the next new data center — or handful — that comes to town ready to pay property taxes and bring jobs. On the other, he’s not looking to change Quincy’s identity. (Or sell of all its land, use all its hydropower or pollute its air, either.)

“I don’t want to sound negative,” he says. “It’s just that naturally our area will eventually reach a point where we’ve had as many as we can deal with.”

He’s just not sure when that point might come.

As for Peter Shelton, his hometown is different from the one he remembers growing up in. But he doesn’t miss the hard farm work he did as a teenager or seeing his community drained of young people who left to find good jobs.

“Our roots are here, so it’s nice to come back,” he says of his family. “I’ve seen this town change ... It’s bustling and that’s pretty cool.”