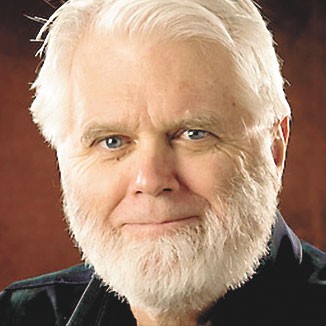

Last week, the Peace and Justice Action League of Spokane brought Pulitzer Prize winner Christopher Hedges to the Bing. The theater was packed. The audience was energized, and Hedges didn't disappoint.

He came to urge rebellion. And he did. Not protest — well, that too, but he's after something more than protest. Rebellion. He saddled up with famous go-it-alone rebels, from Ralph Waldo Emerson to Henry David Thoreau, from the Wobblies to the Freedom Riders and Martin Luther King. He even tossed in the likes of Howard Zinn and Ralph Nader for good measure.

No, there's not much nuance in the world according to Christopher Hedges: Corporate America, capitalists and political sellouts of all kinds are in cahoots. Everything is so clear, as he tells it.

With a single leap, he takes us from George Washington, whose life Hedges reduces to that of a land speculator who today we would expect to find on the board of Goldman Sachs, directly to sellouts such as James Madison, who we're told hated democracy. And, boy, did Hedges ever go after today's faux liberals, Bill and Hillary — both sellouts to corporate America. (There are lots of sellouts.) Of course, NAFTA is at top of his list of sins against America. Nor does Barack Obama escape Hedges' wrath. Obama, he says, has done more to advance the "Big Brother" police state than anyone before.

Hedges makes these giant leaps, from the evils of Wall Street to the tyranny of the NSA, and apparently it's all coordinated. It's quite a stretch to swallow. Don't get me wrong — much of what he says is no doubt true. But it's his sound and fury and giant leaps taken with single bounds that I had trouble tracking. Remember the line from the movie Network? The recently fired news anchor Howard Beale, played by Peter Finch, yells out, "I'm as mad as hell and I'm not going to take this anymore!" Well, the line catches on, his ratings go up, and instead of being fired he gets his own show. Hedges does a toned-down version of Beale to similar effect. He's preaching, and his choir loves this stuff. I even heard a "right on!" or two shouted out.

Still, I was pleased that Hedges took us into the nefarious world of "public relations," which was invented by one Edward Bernays, a nephew of Sigmund Freud. Bernays is noted for having concluded that Joseph Goebbels had poisoned the word "propaganda." So Bernays called it "public relations." Of course, public relations is really all about propaganda. Talk radio is about propaganda. Fox News is largely about propaganda. The advertisements bought and paid for by the interest groups are all propaganda. So why does it work?

To explain propaganda, Hedges heads directly to Walter Lippmann and World War I, and unless you're familiar with Lippmann's work, you could have been left thinking, "My God, even Walter Lippmann was in on the conspiracy?" From there, of course, it's next stop Wall Street and the NSA.

Hedges would have done us a favor had he focused more on Lippmann's classic book Public Opinion. Informed by his World War I experience, Lippmann borrows from both that and Bernays, whose own thinking was informed by his famous uncle. Lippmann argues that distortion is embedded in the very workings of the human mind. Since no man can see everything, each creates for himself a reality that fits his experience, in effect, to use Lippmann's term, a "pseudo-reality." This is how people impose order on an otherwise chaotic world — an order they reflect through the prism of their emotions, habits and prejudices.

But Hedges never gets into this much, beyond making reference to propaganda as a way the "governing they" maintain control. To him it's all so clear, from NSA to Wall Street, bought-and-paid-for commercial television, most newspapers, the White House, all apparently coordinated, seamless even.

His leaps, I suggest, lead him to into false equivalencies. For example, he makes a major error when he indirectly blurs the distinction between Hillary Clinton and any of her possible Republican opponents. Perhaps the Clintons did sell out to corporate America, as did the Republicans — but with an important difference Hedges misses. From Michael Tomasky's recent New York Review of Books article we read a summary of what Hillary accepts and what not one single Republican candidate does: That "inequality is the greatest economic challenge we face." She then blames the standard set of reasons (globalization, technological change, immigration patterns, decrease in workers' bargaining power, high-end compensation and tax policies) rather than the cultural set of reasons the Republicans favor (if only the middle class and poor were more virtuous — that kind of thing.) These important distinctions are lost in Hedges' sweeping generalizations.

Hedges got his loudest round of applause when, while dumping on Bill Clinton's various sins (NAFTA, Wall Street, etc.), he pointed out that one consequence of Clinton's success was to shove Republicans more to the right, "where they have gone insane."

I have to admit, Hedges kind of nailed it there: Recent events on the foreign affairs front would seem to confirm his point. ♦