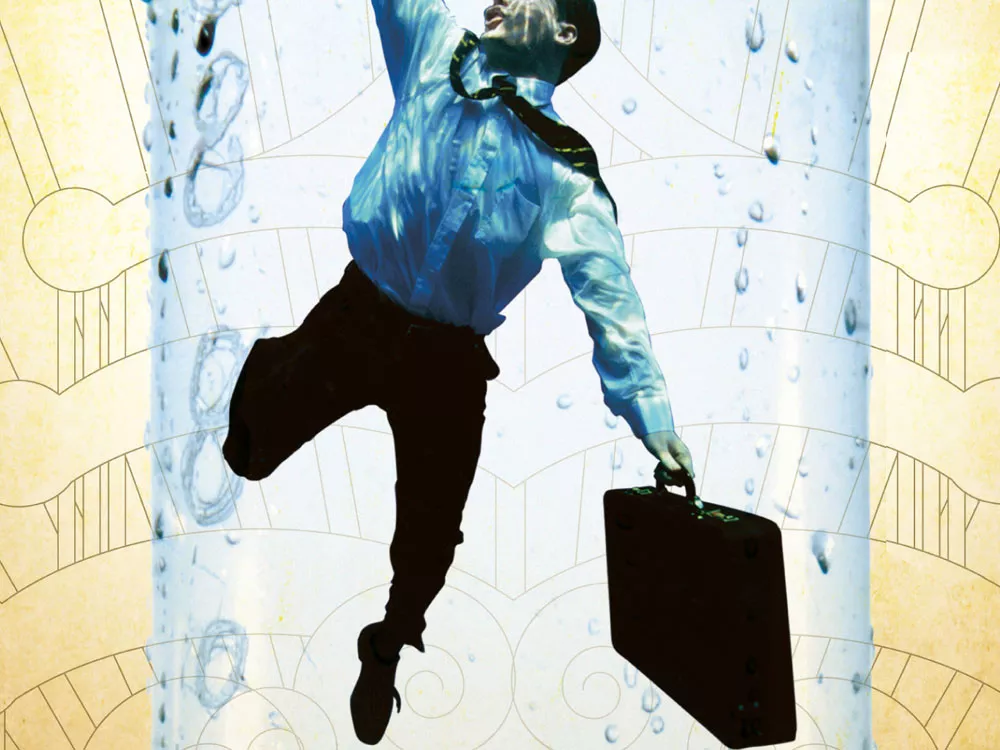

Holy Water opens on a polluted river that’s literally on fire. Earlier, our corporate-schmuck hero rides past rows of gravestones on his morning commute, imagining that he lies beneath every one of them.

Lousy job, lousy marriage, lack of purpose, spiritual emptiness — Henry Tuhoe might as well be dead.

Images of mortality abound in James P. Othmer’s angry but funny anti-corporate satire. The “dark portal” of a highway tunnel seems like “some kind of urban genocide machine.” Henry’s wife has insisted that he get a vasectomy, and as he reaches down to reassure himself about his recently shaved testicles, “he feels as if he’s holding not a surgically altered reproductive organ but two tiny bombs planted by terrorists of the self, waiting to blow his life apart.”

As if on cue, corporate restructuring detonates Henry’s life — blowing him all the way to a fictional Asian nation where he’s supposed to set up a call center for a bottled-water company. Caught between an insane pro-growth monarch and peasant rebels who espouse pacifism but wield machetes, Henry gets his eyes opened to the fact that the magic little kingdom of Galado is actually “a corrupt, filthy, environmentally bankrupt f---ing kleptocracy” in which most people don’t have access to clean drinking water and hundreds of children die every day of diarrhea.

Othmer — who has written a memoir and earlier novel about the fraudulence of advertising — draws characters broadly to score satirical points: the smarmy boss, the desperate suburban-dad beer experts, the Aussie wheeler-dealer, the sociopathic dwarf-dictator, the empowered wife who just joined a coven. But they all have hearts and supply snappy dialogue.

When Holy Water changes tone from satiric to idealistic, however — with Henry and his new Galadonian girlfriend working out a national improvement program combining growth with sustainability — the narrative can get preachy. Still, the native telephone operators’ assumptions about Americans’ underhanded intentions are LOL and spot-on.

In the struggle between cultural preservation and modernity, Henry awakens from his aimlessness and tries to oppose the corporate invaders. But Galado’s culture ends up “being raped by a gang of logos.”