I’m jolted awake by screaming. Someone has just turned on the television in the next hotel room, and now a pundit is yelling at me through the thin walls.

“Democrats and Republicans,” the TV shouts, before it is mercifully turned down a few notches and his words are transformed to garbled notes. I look at my clock. It’s 5:12 am, Feb. 9, Day 31 of the Washington State Legislative Session.

I’m here in Olympia to watch the levers of power get pushed, pulled and manipulated. I want to rub elbows with the lobbyists, smell the money, watch the activists, the reporters, the politicians — even the tourists — jam into one giant capitol dome. I know that people are here for one thing — their slice of the pie. I’m here to see them eat it.

The clock is running. By the end of April, when the legislative session finally — hopefully — ends, legislators will have to close the $4.6 billion budget gap. They might also make it illegal to use fertilizer on your lawn, or legal to buy pot in a liquor store or use a spear for hunting.

They just might.

I try to ignore the mumbling TV next door. Thinking about the sheer insanity of a hulking and unwieldy 21st-century government is enough to keep me awake. I force my eyes shut. It’s going to be a long couple of days.

“TORTURE THEM LONG ENOUGH”

If you’re looking for Rep. Timm Ormsby, the quick-witted Democrat from Spokane, there’s a good chance you’ll find him at the No. 42 bus stop. He’s not waiting for a ride — he’s just smoking, in what he calls “the penalty box.”

But I found him Wednesday morning 20 feet from there, in his tight-quartered office, working his way through a parade of visitors.

First up is lobbyist Jim Hedrick representing various Spokane interests: Greenstone Homes, Sirti and Washington Filmworks, among others. They talk about Rocky and Bullwinkle and Jonny Quest. Then there’s someone from the YMCA.

Waiting for his next appointment — they come in 15-minute spurts — Ormsby explains how Olympia works.

“There’s a lot of similarities between what happens here and sporting events,” he says with a gravelly smoker’s voice, wearing a gray, pinstriped suit. Players are chosen and the game begins. Madness ensues — everyone is desperate to win. Three and a half months later, the clock stops. Then, after a survey of bruises, we see who is victorious.

Ormsby loves the game. He’s talking, talking, talking and I’m just writing. I ask him what he thinks the biggest piece of legislation is this year. Almost before I’m done with the question, he interrupts, “Unemployment insurance reform,” which is supposed to shore up the state’s unemployment program.

Sounds boring, but I make a note of it anyway.

I’m thinking that I should go rustle up some trouble elsewhere, when the next group of visitors rolls in: representatives from the construction industry of Spokane.

Freshmen Democratic Rep. Andy Billig — Ormsby’s 3rd District seatmate — joins the group, and the six of us gather around a table meant for three. Sitting to Ormsby’s right is Wayne Brokaw, an imposing man with a yellow “US-395” badge and a shiny bald head.

Almost immediately, Brokaw, the executive director for the Inland Northwest chapter of the Associated General Contractors of America, brings up unemployment insurance.

“Let’s talk about it, then,” Ormsby cuts in, leaning forward, ready for battle. “It’s hot. It’s not too hot to touch, but it’s warm.”

As unemployment rose during the recession, the taxes collected from businesses ceased to cover the cost of providing benefits to unemployed workers. Over the past two years, the state has paid out about $2 billion in benefits while only bringing in $1 billion.

In order to bridge that gap, Gov. Gregoire in 2009 dipped into the unemployment insurance trust — which was then a sizable $4 billion — to boost benefits for laid-off workers and cut unemployment taxes for businesses.

But as Ormsby speaks, the average business in Washington faces an immediate rate hike of 36 percent, unless something is done.

Brokaw cites numbers from the state’s Labor and Industries department that suggest workers are taking advantage of the state’s programs.

Ormsby’s not having it.

“Those L&I numbers are like people,” he interjects. “You torture them long enough, they’ll tell you what you want to hear.”

As the talk gets heated, Billig, the peacemaker, jumps in.

“What I’m hearing,” he says, “is a recognition that what’s good for the … worker is good for the employer.” Everyone nods, and conversation moves on to more agreeable topics.

Some salutary ribbing breaks out as the meeting wraps, but the elbows feel a bit sharp.

“Your hair’s gotten a little grayer in the last few months,” Brokaw says, teasing Ormsby.

“And your hair’s gotten a little shorter,” the lawmaker cracks back, his face flushing briefly. He talks through it and leans into Brokaw’s space, grabbing and patting the man’s armrest. He shuffles the men out.

It’s 10 am. He has to get to the House floor. First, maybe one more cigarette.

THE BRAIN

Andy Billig and I rush through the crowds in the capitol building. Dozens of Eagle Scouts, in their brown uniforms and red kerchiefs, are lined up in a hallway. State troopers in baby blue are everywhere. YMCA representatives, tourists and people getting ready for a refugee rights demonstration cram into the building. Three lobbyists in crisp suits stand around a TV, watching coverage of some meeting happening somewhere else in the capitol.

Billig and I walk side by side — but because of the crowd, sometimes single-file.

“This place is like a brain,” he tells me, galloping up a marble stairway. “The hard part is being able to find the part of the brain you need.”

The capitol pulsates with intellectual energy. Clumps of people break apart as quickly as they come together, exchanging discrete bits of information and moving on. Olympia is the center of the state’s nervous system, cueing complex actions and providing it with the energy — not to mention the funds — to get it done.

Billig says that later on he’s going to “drop a bill in the hopper” and he invites me to come with him. “It’s not as dramatic as it sounds,” he tells me, and I think it doesn’t sound that dramatic.

But he’s got to get his bill in the hopper, a simple wooden box in the Joel M. Pritchard Library that is the birthplace of every bill in Olympia. By the end of this week, if a bill hasn’t been approved by and passed out of a committee, it’s dead for the session. Rules are rules.

Billig knows this, and he fully expects his bill to be pushed to next year. If it’s ever passed, he says, it’ll allow sick, needy people to deduct hundreds of dollars a year from their taxes, while costing the average taxpayer just pennies. Before he sought co-sponsors, he thought it was a homerun.

Then he tried to get his Republican peers to sign on. Not one did.

“I couldn’t believe it,” he says. But that’s the state of partisanship in Olympia. Republicans won’t sign on to anything that looks like taxes, even while they court the Democratic sponsors they need to get their own bills through the Democrat-controlled capitol.

When the day’s session begins — the official time to vote in the Senate and House — the parties almost instantly head to “caucus,” a members-only meeting where the political parties sequester their members to discuss the day’s strategy.

I’m walking up the north steps of the capitol, and I hear someone yelling, “Is this the tour?!”

It’s Ormsby, cigarette in hand, joking around.

He keeps drawing on his cigarette furiously, again and again, pacing in a small area.

“I’m feeling very exercised,” he says, confusing me.

He tells me they’re trying to vote today on the unemployment insurance reform bill, and he thinks it’s too early. Party leaders are apparently attempting to suss out ways to make everyone happy — Democrats and workers unions, Republicans and employers.

He says he’s not sure if they want him to speak on the floor about the bill or not, but he’s got to go. He heads off, still smoking, and I see him an hour later. In that time, the bill came up for a vote in the House, passing unanimously. Strangely, he doesn’t mention it.

With any luck, the bill will get through the Senate without any substantial changes and will make its way to the governor’s desk.

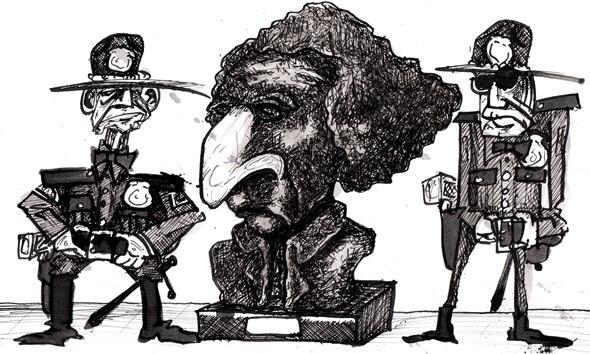

GOLDEN NOSE

It’s 4:00 in the afternoon, and the dome has cleared out. I’m standing next to a large bust of George Washington, his nose buffed and shining gold — the result of hundreds of thousands of hands rubbing it for good luck, I’m told.

A droning noise picks up and at first I think it’s a jet flying overhead. Then I realize it’s coming from the rotunda below me. Looking down, I see four young hippies pacing in a circle, humming in key.

A guard passes and I ask him if this happens much. He motions me to follow him around the corner, and whispers, “They started doing this last week. I don’t know why, but it sure sounds beautiful.” They’re students at the Evergreen State College.

I wait 20 minutes to see if I can talk with them, but the humming continues. I head out.

STOPPING LEGISLATION

The office of Spokane Republican Rep. Kevin Parker — as well as those of Matt Shea, John Ahern and a handful of other GOP House members — is housed in temporary facilities behind the swank, Art Deco-style John A. Cherberg building, where Senate committees meet.

Its thin walls, rickety stairs and fake-wood interiors remind me at every turn that this building really is a trailer.

I show up unannounced, hoping to make an appointment for a later meeting, but Parker and his aide, Ben Oakley, shuffle me in right away.

In his modest office, Parker has a small round table and a chunky-looking Dell laptop. There’s a picture of him and George W. Bush, obviously taken by Parker, left arm extended, camera in hand, aimed back at the two smiling men. There’s another picture of Parker with U.S. House Speaker John Boehner and Eastern Washington’s U.S. Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers.

I tell him I was surprised by the unanimous vote for unemployment insurance.

“It’s a huge issue,” he says. “It’s been a contentious issue. Wait. Don’t say ‘contentious.’ It’s a huge issue.” He pauses. “Never mind. It’s been a contentious issue. Go ahead and say that.

“Employers were going to see their rates rise by 36 percent,” he says. “What this bill does is it keeps it at 5 percent.” For good. The tax cuts are permanent.

But workers are still not working, he says, which made the bill’s passage pressing. “In 2010, two-thirds of the jobs created in the U.S. were in 11 states,” he pauses. “We were not one of them. That’s why it’s so important to us.”

His aide peeks his head in. Reps from Spokane hospitals are here, if a bit late.

“Do you mind?” Parker says affably, and I get up to wait outside. A few minutes later, I’m back in and Parker launches into another of his fast-paced monologues.

“One of the most significant things of the job is the human relationships,” he says. As a member of the minority party, Parker must make nice with more than just the voters.

“You can get so much accomplished if you’re willing to reach across the aisle,” he says. He plays the game, seeking Democrat sponsors for his bills to ensure they don’t die immediately.

“You have 98 House members and you have 49 senators. That’s 98 worldviews and 49 perspectives,” he says. “This institution is not designed to begin or help bills get along. This institution is designed to stop legislation.”

“If a bill is really good, you should be able to get it through,” he says. “There are times where you do wish a bill — a good bill — would sail through.” He stops and thinks about it a little. “There are like seven ways for a bill to die.”

The legislative killing fields: A bill could die with no sponsor. It could die if the House speaker or Senate president puts in an unfriendly committee. It could die in a friendly committee. On its first reading. Or on its second reading. It could die by floor vote. The governor could veto it.

And then there’s the Rules Committee.

TO LIVE, TO DIE

Hundreds of people have assembled on the capitol building’s northern steps. It’s the refugee rights people, still rallying. People are cheering, and a woman yells into the mic, “We are good for America!” More cheers.

Inside the Senate Rules Committee room, the atmosphere is markedly more staid. High-backed wooden chairs slowly get filled with powerful senators.

The seats are almost all taken when Senate Majority Leader Lisa Brown walks in, looking down at her phone. She sits and starts marking the papers before her, glancing to an aide, asking questions.

To get to a vote by the House or Senate, all bills must pass through this committee, one of the most powerful in Olympia. Unlike Ways and Means — which controls the purse strings and therefore only hears bills that affect the budget — Rules is the be-all, end-all for every bill. Members of the committee wield ultimate power over the Legislature’s future.

According to Brown, being on the Rules Committee is “like watching salmon trying to swim upstream.” Bills go here to live, and bills go here to die.

Lt. Gov. Brad Owen, who also acts as president of the Senate, pounds the gavel on the table and turns to Brown.

Because she leads the majority party, Brown sets the rules for the Rules Committee. At the start of each meeting, she tells the committee how many bills each member can “pull,” or move along to the next step in the long, deliberative legislative process.

For this meeting, Brown has allowed each senator on the committee to send one bill of his or her choosing directly to a floor vote — a kind of jackpot for legislation. (Brown told me she can send as many bills as she wants wherever she wants, whenever she wants. No one else in the Senate can do this.)

The meeting begins. She says she wants Senate Bill 5403 to go straight to the floor. “It makes good economic sense,” she says.

Owen asks for comments. There are none.

“Those in favor, say ‘aye,’” he says. The room rumbles with a surprisingly deep-throated “aye.”

“Those ‘no,’” Owen says. Silence. “The ayes have it.”

Despite the decorum, I imagine the committee members as misshapen gods, transformed by their own power. It’s like the room is filled with monsters gnashing their teeth, yowling, begging to send bills forward.

And then there’s Brown, looking calm, normal, lording over the process with whatever rules she desires.

The meeting continues, a mob of senators giving whatever legislation they want — and for whatever reason — the golden ticket.

THE REVOLUTION WILL NOT BE TELEVISED

Despite surprisingly lax security (I get more thoroughly vetted walking into Spokane City Hall), getting into Brown’s office takes little more than asking a guard to tell someone I’m in the hall.

It’s just after nine Thursday morning when I’m led to Brown, who is tapping away on her iPad.

“Come on in,” she says. “I’m just checking e-mail.”

She’s at her big wooden desk, which is decorated with an Obama bobblehead doll. Near the window is a large table with six seats around it. There’s also a more casual sitting area, with a couch, coffee table and a handful of chairs. Everything feels historic and welcoming, like a homey museum.

Under the coffee table’s glass top, Brown keeps a collection of campaign buttons: Jesse Jackson ’88, JFK, McGovern, an artsy Jimmy Carter button that has no words. Near her desk rests a turntable and a small collection of vinyl. Gil Scott Heron’s The Revolution Will Not Be Televised faces out, but she also has the Sex Pistols, the Clash, Billy Bragg and John Denver.

I’ll be sitting in on a few of her meetings this morning — with land-use advocate Kitty Klitzke, some representatives from a building managers’ association, other folks from the United Way — so I plop down on the couch.

I bring up the unemployment insurance bill that passed the House yesterday.

“That will hit the [Senate] floor tomorrow,” Brown says without looking up, surprising me. It’s been fast-tracked. Brown’s caucus likes it, as does the Senate minority leader, Mike Hewitt. It’s going straight to the floor for a vote on Friday.

Brown rattles off the bill’s selling points. It will increase benefits without costing the state or employers a thing. In fact, it will save employers $300 million in the next year alone.

And unemployed workers will see their weekly checks temporarily go up by $25, at a cost of about $68 million.

So how can they pull off such a feat? The $98 million needed to accomplish all this will come from the federal government, which is paying states to modernize their unemployment insurance programs. Most states’ programs were barely afloat after the recession, but with $2.4 billion still in the bank, Washington’s unemployment fund is the strongest in the nation.

“We had what I guess you could call conservative, or fiscally responsible, policies” around unemployment insurance, Brown says. “We could last the worst recession for 14 months.

“Which reminds me,” she says, calling in an aide and telling her she wants to schedule a vote for a memorial letter.

If the bill passes and gets signed by the governor, Brown wants the Legislature to send a memorial — like a super letter approved by both houses — to the U.S. Congress, reminding them of Washington’s solid footing.

“We basically want to tell them, ‘If you bail out other states, we should get something,’” Brown says.

Her first guests arrive and Brown stands. Once again, I witness a parade of lobbyists, activists and officials. The clock’s hands spin and I’m escorted out before a meeting of important legislators.

ACROSS THE DOME

Friday afternoon — Feb. 11, Day 33 — and members of the House and Senate, Democrats and Republicans, congratulate themselves.

Gov. Chris Gregoire is signing the first completed legislation of the year.

Earlier in the day, the Senate passed unemployment insurance reform by a vote of 41-4. The governor’s conference room was packed for the ceremonial bill-signing, with leaders from both parties patting each other on the back.

“I do think this is a historic moment,” the governor says to the gathered officials. “It’s all the art of compromise here. No one got everything they want … but unlike times past, it was done [in an] absolutely bipartisan [manner]. And even sometimes more importantly than that, it was done across the dome. … Business and labor came together, which doesn’t happen all that often.”

KNEELING BEFORE THE KING

I’m in the last meeting I’ll attend in Olympia — that of the powerful Ways and Means Committee, the controller of the purse.

Lobbyists, activists and bureaucrats are the main attendees, and even as the meeting is underway, a constant murmur is heard through the hall.

Watching the unemployment insurance shell game — federal cash running through the state’s coffers to help businesses save four times what’s being paid to the unemployed, all in an effort to “boost the economy” — piqued my interest in how lawmakers divvy out the state’s billions of dollars.

Now I’m watching it happen.

Testimony begins on various bills — regarding flood control in King County, mineral extraction in Jefferson County, and the taxation of zoos — and there’s a feeling of princes and paupers kneeling before the king, politely asking for some of his treasure. Demanding, albeit gently, a chance at the teat.

Near the two-hour mark, a couple of guys representing the concrete industry testify. One of them, taller and better-dressed, tells the committee he won’t speak long. He wants to let his companion from “the real world” talk.

“I’m just a mercenary,” he says. The lobbyist gets some laughs from the senators.

His companion — rotund, with a grey ponytail — tells the senators that the sand and gravel business is hard enough, it doesn’t need any more government intrusion — it could do without additional taxes.

Returning to their seats, smiling and laughing, the mercenary tells some lobbyists he passes, “You have to do something to get their attention.” A wink, and an apology of sorts for calling them all mercenaries.

Time’s up, I need to get out of Olympia. As the saying goes, watching laws get passed is about as pleasant as watching sausage get made. And I’m a vegetarian.