When it was clear there wasn’t room in schools for the full story of black history, Khalid el-Hakim built a bus.

It is a history he sees written in racist tchotchkes and burned crosses. In photographs and accounts of lynchings. It was a history told to him not by educators, but by militants and poets. By platinum-selling artists.

“When I started off in junior high school,” el-Hakim says, “there was nothing much more than slavery, Harriet Tubman, Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks.”

When he caught glimpses of the hundreds of years of torture, murder and injustice and learned tales of the many men and women who rose up against it, it wasn’t in the pages of a textbook.

“It came straight from hip-hop,” el- Hakim says. “It came from Public Enemy, KRS-One. It came from Rakim. It came from X-Clan. It was my first time hearing Farrakhan’s name, Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X.”

He began to study these people. On a trip through Tennessee in 1991, this curiosity with history collided with the present day. At a gas station, next to the register, el-Hakim found a little figurine for sale. It was a black child, squatting over a chamber pot, clutching a slice of watermelon.

He has collected ever since, pieces ranging from a Klan scrapbook to the letters of Booker T. Washington, in the hopes that people would see these things not as archival data, but as a living continuum of experience that continues to the present day.

A middle school social studies teacher, el-Hakim has taken the collection around the country to schools and universities for a decade and a half, looking to provide tangible context of what African-Americans endured. His mobile museum stops at Gonzaga University this Friday.

“When you teach [Dr.] King even,” el-Hakim says, “you might not teach the Jim Crow era. You might not teach Aunt Jemima. Or you might not teach lynching. For a hundred years of reconstruction, lynching was a reality, and that isn’t taught.”

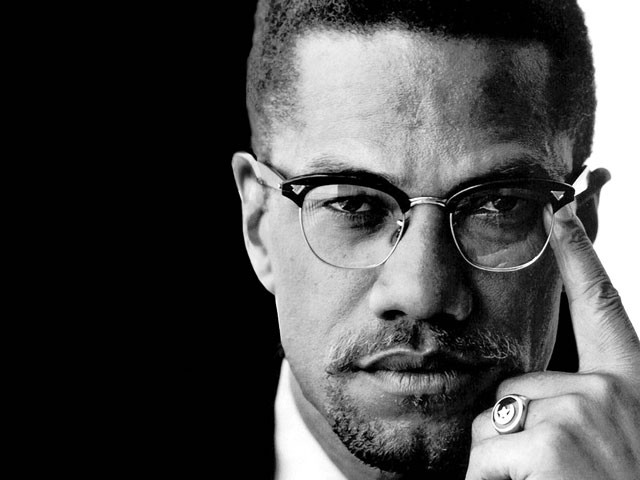

A full context is especially necessary for Khalid el-Hakim’s latest exhibit, Necessary!, which chronicles the life of Malcolm X.

History has cast Malcolm X as the frightening, militant opposite to Martin Luther King Jr.’s peaceful resistance. Before Malcolm X came along, though, King was seen as radical. By pledging to wage the war for freedom “by any means necessary,” Malcolm X transferred some of the fear that blacks across the South felt to the doorstep of the white American psyche.

“He’s a bitter pill to swallow in America,” el-Hakim says. “Malcolm told America how ugly it was to its face.” Malcolm’s own life knew little besides brutality, and so “he expected nothing but the brutality.”

Affected by Marcus Garvey, the violence of the Jim Crow South and, of course, Elijah Muhammed, Malcolm X would go on to affect countless others. Huey Newton. Public Enemy. Spike Lee.

Necessary! — a collection of over 150 pieces — begins with slavery and ends with Tupac, attempting to paint a picture of Malcom X’s formation and the long tail of his impact.

El-Hakim says that the artistic militancy of black culture, especially in the early ’90, used leaders like Malcolm as a template to confront contemporary racism. He uses Public Enemy’s It Takes A Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back and Spike Lee’s Do The Right Thing as two examples.

Even as we’ve elected a black president, it’s clear that racism is still with us. El-Hakim references the 2009 New York Post cartoon depicting Obama as a renegade chimpanzee. “The image of black people being less than human is nothing new,” he says. “The Negro as beast.”

“These are realities,” el-Hakim says, “that, as Americans, we have to deal with.”

Malcolm X knew he would die violently. He said so in his autobiography.

Malcolm’s father and his uncle had died at the hands of white men, he writes in the first chapter. “It has always been my belief that I, too, will die by violence. I have done all that I can to be prepared.”

As he predicted, on Feb. 21, 1965, Malcolm X indeed lay dead — his body prone on the stage of Manhattan’s Audubon Ballroom, his left middle finger shattered, his chest opened by a shotgun blast — at age 39.

At his funeral six days later, the actor Ozzie Davis delivered a eulogy that painted the man with a care and nuance that is often lost to the polarizing influences of time.

“There are those who will consider it their duty, as friends of the Negro people, to tell us to revile [Malcolm X], to flee, even from the presence of his memory,” Davis said. “They will say that he is of hate — a fanatic, a racist — who can only bring evil to the cause for which you struggle! And we will answer and say to them: Did you ever talk to Brother Malcolm? Did you ever touch him, or have him smile at you? Did you ever really listen to him? … For if you did, you would know him. And if you knew him, you would know why we must honor him.”

Almost exactly 46 years later, helping America know Malcolm X is exactly what Khalid el-Hakim intends.

“Necessary!” • Friday, Feb. 25, from 9 am to 5 pm • Gonzaga University Crosby Student Center • Legacy of Malcolm X Faculty Panel • 7 pm • Jepson Wolff Auditorium • Free • 313-4105