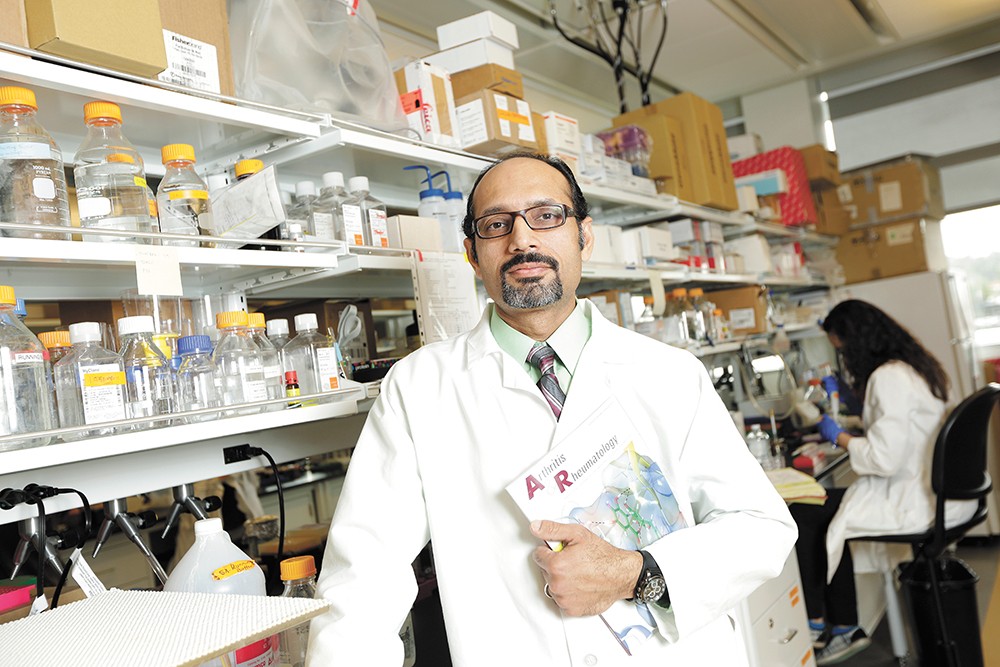

The face of Salah-uddin Ahmed, an associate professor at Washington State University's School of Pharmacy, isn't quite on the cover of the February issue of the medical journal Arthritis & Rheumatology, but the next best thing is.

The cover has a stylized illustration of the molecule that his research has revealed may become a new tool in fighting rheumatoid arthritis.

"This is the actual molecule — this is our study," Ahmed says. "I'm really proud of this study."

Ahmed writes it down on a yellow slip of paper so I can get the spelling right: epigallocatechin-3-gallate, or "EGCG" for short.

After 10 years studying the causes and treatments for rheumatoid arthritis, Ahmed's latest discovery centers on this molecule — the same substance you gulp down every time you drink a cup of green tea. At times, the Food and Drug Administration has sent companies warning letters for making big, untested claims about the power of "Green Tea Extract." But there have been studies that show promise.

Ahmed's is one such study. After rats in his Spokane lab were injected with EGCG for a short period of time, he found there had been a significant reduction in the severity of rheumatoid arthritis.

"This is very nice preclinical success," he says.

Let's break down why Ahmed believes this happened: Rheumatoid arthritis isn't like osteoarthritis, which is all about the wear and tear of the cartilage between joints, whether from age or distance running. Rheumatoid arthritis, on the other hand, is an autoimmune disease where the body malfunctions, sending proteins that normally scavenge for intruders to combat its own tissue.

"The immune system gets some misinformation, and they start attacking," Ahmed says.

The efforts to study rheumatoid arthritis have often focused on a handful of immune-system proteins, with names like TNF alpha and Interleukin 1.

In a healthy body, these are front-line troops sent to fight infections. But sometimes something goes haywire with the signals in the immune system, and the body keeps pumping out these proteins, even when there are no infections to fight.

With no target to battle, the proteins wage war on the body itself.

Some of the most effective anti-rheumatoid arthritis drugs currently on the market, like Enbrel from Pfizer, focus on wiping out the troops, removing the problematic proteins from the field of battle.

Yet these drugs can be quite expensive, and come with major side-effects: Unsurprisingly, blocking proteins that fight infection can lead to a higher risk of infection.

In Ahmed's experiment, instead of targeting the troops, he took aim at muzzling the commanders. He targets one of the proteins — called TAK1 — that sits in the center in the pathways between the other malfunctioning proteins, signaling them.

That's where the green-tea chemical comes in. "What we found was that EGCG was able to inhibit this protein," Ahmed says. By cutting off the lines of communication, the green-tea molecule didn't halt the production of these proteins entirely, but slowed it down enough to alleviate arthritis symptoms. At least it did in rats.

Ahmed says it's possible that the tea itself could serve as a treatment. Maybe a cup of green tea a day will keep the doctor away, alleviating the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis over time. Or possibly the EGCG could be extracted, and turned into a new drug.

Of course, all that possibility is far in the distance: Ahmed's study hasn't been replicated yet, and it hasn't been tried in humans. Plenty of studies that show possibilities of clinical promise in the future fizzle out in latter steps.

"There's no guarantee, frankly speaking," Ahmed says. "You're always on the edge when you're in science. And especially when doing cutting-edge science, you know."

Even if it doesn't work this time, here's what Ahmed is really excited about: Not EGCG, but the discovery of TAK1's impact on the proteins involved in autoimmune diseases.

"That's the take-home message. We have identified a target here for the treatment of other diseases," Ahmed says. "Can we use this information to apply to other diseases?"

There are plenty of other autoimmune diseases in which inhibiting TAK1 might be beneficial.

"So, if this plays a role in arthritis, but if it also plays a role in, let's say, type 1 diabetes or multiple sclerosis, just as an example — then this has more implications." Ahmed says. n