If you've ever been in the job market, you've probably read words similar to these: Drug Free Workplace. Pre-Employment Drug Screening Required.

Although the 2012 initiative legalizing recreational cannabis in Washington passed with 56 percent of the vote, employers can still require prospective employees to submit to drug tests and deny them employment if they test positive for THC, the psychoactive ingredient in cannabis.

While there's broad agreement, even among pro-marijuana advocacy groups, that employers have a legitimate interest in keeping their employees from coming to work stoned, there's also broad agreement that the primary means of testing for the drug is a flawed tool that's unlikely to go away anytime soon.

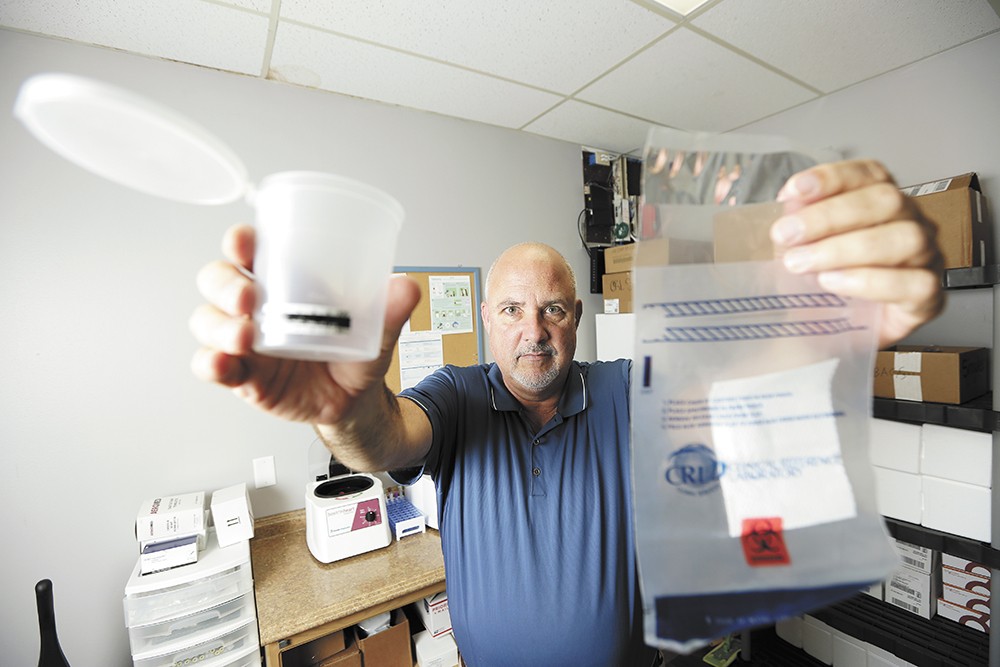

"There's no way to tell how long ago [an employee] smoked," says Doug Thayer, owner of a local franchise of ARCpoint Labs, a national chain of testing labs.

Some drugs considered more harmful, such as cocaine or methamphetamine, exit a user's system within a day or so. But marijuana, depending on someone's frequency of use and body weight, lingers for weeks or longer, meaning that a drug test would catch both the employee who dabs before work and the employee who smoked a joint weeks ago. "We've had people who've had it in their system for months and they can't get rid of it," says Thayer.

Employer-based drug testing became increasingly common in the 1980s amid the War on Drugs. Then-President Ronald Reagan issued an executive order in 1986 declaring the federal government, the nation's largest employer, as a "drug-free workplace" and mandated testing for employees in some positions while encouraging the private sector to follow its lead. Around the same time, studies found that drug use hurt worker productivity and made them prone to accidents, spurring more private employers to begin screening. Testing companies grew into a multibillion-dollar industry.

The initiative that legalized marijuana in Washington is silent about employer drug testing, but past court rulings are mostly unhelpful to stoners seeking gainful employment. In 2011, the Washington State Supreme Court ruled that a company could fire an employee for marijuana use, even if they're using it for medically sanctioned purposes.

However, in 2000, a state appeals court ruled that the city of Seattle, because it was a government entity, could only drug-test employees if their position was related to public safety or there was reason to suspect they were high at work. The city of Spokane, the area's largest employer, has a zero-tolerance drug policy that includes marijuana, according to city spokesman Brian Coddington. However, he says that only public safety employees, heavy equipment operators and drivers are subject to pre-employment drug screens. Other employees can be tested with reasonable cause, he says.

"We believe that it invades the privacy and dignity of a person to be asked to pee in a cup," says Doug Honig, communications director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Washington. He says that more employers are beginning to realize the antiquated Drug War origins of drug testing and are abandoning the practice.

In 1996, a survey from the American Management Association found that 81 percent of companies conducted drug screenings. Since then, new research has undermined previous claims that drug screening boosts productivity and enhances safety. Now, with medical marijuana legal in 25 states and the District of Columbia, most surveys report that roughly half of U.S. workers are subject to employer-based drug screening of some sort.

Thayer says that companies operating in states such as Idaho get a better rate on workers' compensation plans if they conduct drug screenings. But Washington, he says, is different; employers are more inclined to treat pot like alcohol.

"You wouldn't want to drink at work; you wouldn't want to smoke at work," he says of the standard that some Washington companies have adopted.

Kevin Oliver, executive director of the Washington chapter of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, says his organization, like the ACLU, opposes employment prescreening and random tests. However, both NORML and the ACLU support allowing employers to drug-test employees if they suspect they're impaired or they cause an accident.

A blood draw would determine if a worker had used marijuana within the previous few hours, but Oliver says that courts have found that approach to be unduly excessive if used by an employer.

Currently, companies and universities are working on mechanisms, including oral swabs and breathalyzers, that would detect if someone had recently ingested cannabis. But they're still being developed. Thayer adds that even if they were available, there's no standard for how much THC someone should have in their system before they are considered impaired, as there is for blood alcohol levels.

Oliver says that he's been to Olympia and Washington, D.C., to lobby for changes to marijuana laws. But he says that his lobbying efforts have been focused on making the tax code friendlier for marijuana businesses or allowing home grows for Washington residents, not employer drug testing. Besides, he says, employers already have broad latitude to dismiss their employees.

"Employers can fire you just because they don't like the way you part your hair in Washington state," he says. "So there's not a lot people can do." ♦

CRIMINAL RECORDS

Last year, Spokane became the first city in the state to allow people with past marijuana convictions to clear their records. Has anyone taken them up on the offer?

When Spokane City Council President Ben Stuckart introduced an ordinance last fall that would allow people found guilty of misdemeanor pot possession to have their records retroactively dismissed, he took to Facebook to say his measure wasn't about marijuana but about second chances.

The council passed the ordinance on a 6-0 vote in November, and Stuckart noted that individuals with these convictions tend to disproportionately be minorities and that having this mark on their records could be a barrier to housing, education and jobs.

The ordinance, which went into effect in January, made the front page of the Huffington Post. The Center for Justice, a nonprofit law firm, offered to help walk people through the process. But so far, Julie Schaffer, an attorney at CFJ, tells the Inlander she hasn't had a single client use it and doesn't know of anyone else doing so. City Prosecutor Justin Bingham isn't aware of any motions being filed using the ordinance, which he chalks up to a lack of public awareness.

— JAKE THOMAS