Most of the crew has been on set since before sunrise.

It’s now past 5 in the evening on a cooler-than-average August afternoon, and the dozen or so cargo-pant-and-T-shirt-clad group of 20- and 30-something men will keep filming until sunset. The next day, some of them will get up before dawn to film again; others plan to start editing footage that night.

“Cameras rolling!”

“Aaannd action!” yells director Adam Harum, standing behind a monitor showing the main camera’s angle, several pages of script rolled up and tucked into his back pocket.

A shirtless actor, also the project’s director of photography, comes barreling down a grassy slope at sprint speed, yelling “Get out of the house! Get out of the house!”

On a pine-tree-covered hillside overlooking the gently rolling hills of Orchard Prairie in northeast Spokane County, Harum and his crew have picked up and moved their equipment several times before they’re satisfied with the angle of the quickly changing evening sunlight. All of this effort is for a scene that, when finished, will only amount to about three seconds of footage for a roughly 10-minute episode of the locally produced sci-fi web series Transolar Galactica.

The passion project of five young men — all graduates of Eastern Washington University’s film program — Transolar Galactica has gained an impressive following of sci-fi fans across the world in the past year and a half. Last fall, the series raised more than $30,000 through a Kickstarter campaign to fund its second season, setting a record for the most money that’s ever been crowdsourced via the site for a Spokane-based project of any kind.

Despite its success, Transolar Galactica isn’t widely known locally since it’s geared toward such a specific demographic — but not all filmmaking is about blockbusters and the big screen. In Spokane and across Washington state, a core of dedicated filmmakers like Harum and his peers are focusing their talents more toward independent and small-budget projects, like exclusively online content and small-budget films that lean artistic and end up at regional film festivals instead of on megaplex screens.

Currently, Washington’s film industry employs an estimated 3,400 people — likely between 150 and 200 working out of Spokane — and in the past six years, film projects have brought more than $213 million into the state, according to Washington Filmworks, a Seattle-based nonprofit that promotes the state’s film industry.

But at the same time, Washington is losing out on big TV series and films — even some written to be set in the state, like AMC’s The Killing and the Twilight film franchise.

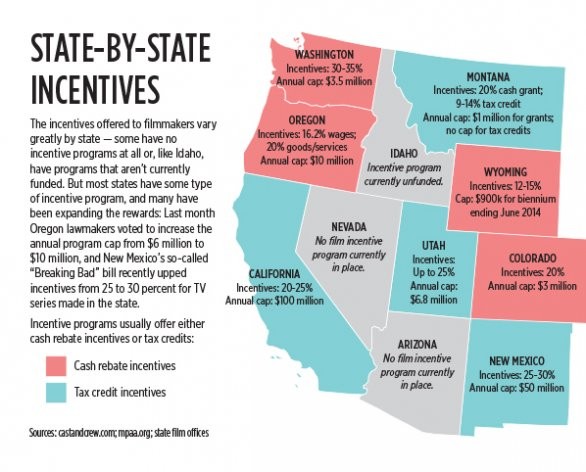

Industry analysts say the key is money. Of the 39 states with some kind of financial incentive for film productions, Washington falls near the bottom of the list. The state’s incentive program, managed by Washington Filmworks, offers up a modest $3.5 million per year, compared with other states that annually give away tens of millions of dollars in tax credits, grants or cash rebates to film productions.

During the 2011 legislative session, Washington lawmakers let the state’s Motion Picture Competitiveness Program lapse for a year. Industry advocates predicted the film business would collapse. It didn’t, but Washington arguably lost much of its edge in the highly competitive filmmaking game during that time. Not renewing the incentives undoubtedly meant significantly fewer feature films made in the state between late 2011 and the first half of 2012 than in prior years. It also forced production specialists, actors and directors to do what they do best: improvise.

Rather than chasing down work elsewhere, industry creatives who stayed in Spokane through the film incentive’s lapse chose to focus on the varied work outside of feature films. More energy went to building up the industry from a grassroots level, through web-based projects like Transolar and events like the annual 50 Hour Slam filmmaking competition, organized by Adam Boyd, one of Transolar’s creators. Spokane-based professionals also found work on the sets of local commercials and small-budget short films largely unaffected by the incentive program’s lapse.

For Harum and his counterparts, that diversification into other areas of film work offered opportunities to grow and gain experience that is proving invaluable now that Washington’s film incentives are back.

“That’s what’s exciting — even though the feature side has been slow — is seeing how we branch out and have been going in other directions,” Harum says, standing off to the side of the crew while they move equipment to a new location and wait for the sun to slightly change its angle.

“You just have to adapt in the industry, otherwise it dies, and I think we’re adapting in an interesting way,” says Harum. “Technology has changed so much even in the last six years, and that’s making it possible for people who would never be able to afford to make a movie to suddenly have access to that.”

And starting in mid-2011, when feature film work in and around Spokane became almost nonexistent, Harum says it also forced the industry’s more experienced professionals to jump aboard smaller projects to stay busy and keep working.

Spokane got one of its first starring roles on the big screen with 1985’s Vision Quest, a coming-of-age saga about a high school wrestler from Spokane with big dreams. Other widely distributed films would follow, but Spokane didn’t get its name on the map until around the late ’90s and early 2000s.

Hollywood began to take note of the diverse landscapes in and around the city — from forested mountains and rolling farmland to arid, sagebrush-dotted expanses and century-old farming towns — along with the relatively inexpensive cost of making a movie here.

Another early game-changer for Spokane came in 1999 when North by Northwest, then a young, small production company, released The Basket, entirely written and produced by a team of locals, including North By Northwest co-founder and co-owner Rich Cowan, also the film’s director.

“It was hard to start out in the beginning,” Cowan recalls from his office at the company’s headquarters in a historic brick building just north of the Spokane River.

“It was always a dream to bring production into Spokane, and why not? We have a great city to shoot in, we have infrastructure here, we have an airport close by. You look out the window here and it’s a back lot,” Cowan says, gesturing to the window behind him overlooking the pavilion in Riverfront Park and downtown Spokane.

Over the years, North By Northwest has diversified outside of movies and commercials. Most recently it added a web division to complement its core production work.

Most of the films North By Northwest makes aren’t big box-office hits anyway, and that’s for a reason, Cowan says. In an ideal year, he says, the company tries to land no more than four feature films, focusing on projects with budgets between $2 million and $8 million because most projects in that range hire local crews in lieu of transporting their own team to the set.

“We have a crew of great technical people here in Spokane, and it’s my responsibility to keep them working so they can stay in Spokane,” he says. “That’s what it’s all about is jobs.”

Because of the way the state tracks industry employment, and because many locals work as freelancers on film projects, it’s hard to calculate how many people the film industry employs in Spokane. Cowan’s best bet? Somewhere between 150 and 200 people.

North By Northwest certainly isn’t the only force making the Inland Northwest a viable place to make films. Other creative agencies in the area include smaller media production studios that largely focus on commercials for TV and radio, online campaigns and other related work. Of the dozen crew members at the 16-hour Transolar Galactica shoot, the majority work day jobs at some of these local companies. They’re giving up an entire Saturday to volunteer their expertise in camera operation, audio, costume work and makeup in part because of the project’s minimal budget, but also to gain valuable on-set experience. Most are graduates of local film and broadcast programs at Eastern Washington University, Gonzaga and Washington State University; some have worked on projects in Seattle, Portland and Vancouver, B.C. — even Los Angeles.

But with all these resources and infrastructure at hand, shouldn’t Spokane be landing more film work?

The idea to offer attractive financial incentive packages to lure filmmakers within a state’s borders is nothing new. Proponents of government economic development programs have long touted the benefits of reducing taxes and offering other bureaucratic breaks to specific industries with the rationale that doing so will help that industry establish itself in a certain place, thus providing livable wage jobs and generating revenue back into the local economy.

Offering economic incentives to filmmakers was spearheaded by Louisiana back in 2002. Since then, Louisiana — nicknamed the “Hollywood of the South” — has become a major U.S. film hub, third only to L.A. and New York City in the number of films and TV series being made there. According to its film office, more than 300 film and TV productions have been shot in Louisiana since 2006. The program is lucrative for filmmakers: Productions that spend more than $300,000 in-state get a 30 percent tax credit on that spending, as well as a 5 percent credit for up to $1 million spent on Louisiana wages.

Here’s a catch: Because most of these films are multimillion-dollar productions, that in-state spending often exceeds the production’s income tax liability to the state. To address that, the state — other states with similar incentives have followed suit — allows productions to transfer these excess credits by selling them to another state taxpayer or back to the state at an 85 percent buyback rate. The state, and others with programs modeled after Louisiana’s, justifies these measures by asserting that when more film productions come to the state, money will be generated back into its economy.

New Mexico was another early adopter, also launching its filmmaking incentives in 2002. This year the state passed new legislation that sweetened its tax credit incentives from 25 to 30 percent for TV series shooting more than six episodes in New Mexico. The measure was fondly dubbed the “Breaking Bad” bill after the hit AMC show, filmed and set in the state. New Mexico’s program caps out at a total of $50 million in credits annually, attracting many widely released films looking to pad their budgets.

But not all states with film incentives have had such success.

An internal audit of Iowa’s incentive program in 2009 found that a lack of oversight and abuse of the state tax credits allowed producers to buy, among other things, luxury cars for personal use using the credits. The program has since been shut down, and the former manager of the Iowa film office was criminally prosecuted.

Controversy over the amount of tax incentives being handed out to filmmakers has troubled other states, including Michigan, where lawmakers facing massive budget deficits have had to decide whether to curtail the 42 percent tax credit, which has been credited with fostering the film business and helping to buoy the state through the auto industry crisis. Later this year, Michigan’s annual film incentive cap will be cut in half, from $50 million to $25 million.

It’s because of Michigan’s generous incentives that Spokane lost to Detroit the opportunity to host the filming of the 2012 Hollywood remake of Red Dawn, a film set in Spokane.

Closer to the Inland Northwest, neighboring states present plenty of competition. Oregon is home to a much larger annual incentive fund that last month was increased from $6 million to $10 million by the state’s Legislature. Filmmakers also bypass Washington and head north of the border to Vancouver, B.C., to take advantage of incentives. In past years, films made there have cashed in as much as $250 million annually. (Washington’s other border state, Idaho, hasn’t been able to offer financial incentives to moviemakers since its program, set up in 2008, has been left unfunded.)

In Washington state, the $3.5 million in funds reserved for qualifying film productions this year has already run dry. And as a result it’s unlikely any new projects with a budget qualifying for the incentives will start production in Washington through the end of the year.

In Washington, the incentive program works like a cash rebate. Productions qualify by spending a minimum amount in state for goods, services and labor: $500,000 for motion pictures, $300,000 for episodic series and $150,000 for commercials. After those spendings are audited by Washington Filmworks, productions that prequalified receive 30 percent of what was spent here back from the state.

The incentive program is funded through a portion of business and occupation tax liabilities owed to the state. Corporations or individuals can choose to contribute to the program’s fund, and receive a dollar for dollar credit of up to $1 million against their business and occupation taxes owed to the state.

Proponents of Washington’s Motion Picture Competitiveness Program argue that while its annual limit is one of the smallest in the U.S. — only five states have smaller film incentive funds — it’s enough to support a thriving independent film scene in both of the state’s film hubs, Seattle and Spokane.

“When people are making a film under $5 million, we’re one of the first calls,” says Washington Filmworks director Amy Lillard over the phone from the organization’s Seattle office.

As to why there aren’t any big TV series that are filmed in the state, it’s simply because the incentive program is not large enough to support an ongoing larger budget project, Lillard says.

“I get asked all the time ‘Why isn’t Grey’s Anatomy filmed here’ and The Killing and other shows,” she says. “It’s because we can’t support it from a business standpoint. We can support it from an infrastructure standpoint, but not the business side.”

When Washington’s Motion Picture Competitiveness Program was up for a vote before the state Legislature in 2011, the bill originally called for a larger annual sum to fund the program, recalls state Sen. Jeanne Kohl-Welles, D-Seattle, who co-sponsored the bill with former state Sen. Lisa Brown, D-Spokane. But because lawmakers were faced with making up a massive state budget deficit at the time, the bill didn’t pass, and the program was not renewed until a second try to bring it back to prior funding levels during the following year’s legislative session.

State film industry advocates like North By Northwest’s Cowan are, for the most part, simply relieved to have the incentive program back in place and remain hesitant to chide lawmakers for not diverting more money to the industry.

Meanwhile, critics of incentivizing the film industry are quick to point out that the state programs are creating a race to the bottom, as states try to outdo each other in luring Hollywood. They argue that Washington state policymakers should be focusing more on lowering barriers to make the state an attractive place for all industries, not picking and choosing certain industries over others.

“What is our state government — the Disney corporation? Why did they choose this industry to promote, taking $3.5 million from current profitable businesses in order to bribe another company to come here?” asks Paul Guppy, a researcher at the Seattle-based Washington Policy Center, a nonprofit public policy think tank. “We have to ask ourselves: Is this what the state and local government are for — to promote competitive business programs against other states when we still won’t win?”

In a similar mindset, Transolar Galactica producer Adam Boyd, who also co-owns a Spokane-based media production company called Purple Crayon Pictures, says he personally believes it would be more beneficial for everyone if all states ditched their existing programs to incentivize the film industry.

But Boyd also notes that Washington’s incentives aren’t necessarily in place to simply encourage big, out-of-state projects to come here: “It’s also about investing in the industry in Washington.”

Later this month, North by Northwest is scheduled to start shooting a new feature film in Spokane called West of Redemption. Casting for the lead roles took place about two weeks ago, and the film’s director is Seattle-based, Cowan says. Until that starts, the company is staying busy shooting local commercials and working on other projects.

On a recent sweltering August afternoon, a small North by Northwest crew — along with a few advertising specialists from the local agency whose client the shoot is for — is gathered around a cool, inviting swimming pool in the backyard of an unassuming South Hill home. An actor with a bushy brown mustache stands next to the pool, wearing khaki cargo shorts and a Mt. Rushmore tourist T-shirt underneath a red-flowered Hawaiian-style shirt unbuttoned in the front.

As the actor awkwardly waits poolside, holding a plate of raw steaks in one hand, barbecue tongs in the other, the 10-person crew moves around their filming equipment to prep for the next shot.

Without knowing the shoot is a TV commercial to promote one of the area’s casinos, a casual observer might mistake it as the set of a feature film. High-end digital cameras sit on tripods around the backyard, and a makeup artist waits nearby with a brush in her hand, ready to touch up the actor’s face in between takes on a sticky, 90-degree day.

It may all be for a 30-second TV commercial, but you wouldn’t know that by the way the director shouts “Action!”