Today, hospitals and doctors' offices are full of sleek and shiny equipment, high-tech wonders that spin, scan, analyze and probe. They can track brain waves and heartbeats. They can read the composition of blood and tissue. X-rays, MRIs and CT scans have allowed medicine to make glorious strides and save countless lives.

But amid all that buzzing and scanning, many experienced doctors worry they're neglecting a simpler, perhaps even more important skill: the physical exam.

"The electronic medical record and advanced imaging technology have not only seduced doctors away from the bedside but also devalued the importance of their role there," Stanford University's Abraham Verghese says in an editorial in The BMJ (formerly the British Medical Journal).

Anyone who has come to the doctor's office with a problem knows what it's like: The cold stethoscope against your chest. The light peering into your eyes and ears. The thermometer and the blood pressure cuff. "Turn your head and cough."

Those simple interactions can communicate vast amounts of information to a skilled doctor — they can save patients and the medical institution money by eliminating needless tests and by catching maladies far before they become much worse.

George Novan, associate dean of the college of medical science at WSU-Spokane, is an evangelist of sorts, trying to spread the good word about the physical exam.

"I came into medicine when there was much more reliance on [medical] history and physical exam skills," Novan says. "As we've become more high-tech, and as we've had more and more interactions with computers, there may be a tendency to relegate medical exams further down the list."

On the first day of class, he sometimes shows his medical students a slide show. Click. A slide of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Click. Doyle's teacher, Joseph Bell. Both were physicians. Doyle based his iconic character, observant detective Sherlock Holmes, on Bell, who wrote A Manual of the Operations of Surgery and lived at a tipping point where new innovations made actual medical diagnoses possible.

"This is medical detective work," Novan says, bringing the point home. "In an era before there were X-rays, before there were MRIs and CAT scans, there were physicians able to diagnose things based on listening — listening to the patient, listening through the stethoscope and examining with their hands."

Physical exams and conversations with patients can't tell you everything. An X-ray, for example, can reveal evidence of pneumonia much more clearly than a stethoscope. But the physical exam often can tell doctors which test to use or not use in a diagnosis.

"An echocardiogram, which bounces sound waves off the heart valves — it's basically sonar for the heart — will do a much better job at defining a valve abnormality than listening for murmurs," Novan says. But is it best to give every patient an echocardiogram, he asks, "or would it be better to listen to a heart murmur and then have an echocardiogram?"

A Johns Hopkins program trains doctors to differentiate benign heart murmurs from dangerous ones with only a stethoscope. Echocardiograms are expensive. If a skilled doctor can rule out the need for one, it saves everyone a lot of money.

"I think the patient-listening doctor who does a focused physical examination can get to the bottom of most things without laboratory or imaging tests," says Matt Handley, medical director for quality at the Group Health Cooperative. Some physical exam techniques, he says, like testing the size of the spleen or liver, are unreliable. But others are superior to tests: A physical exam and patient history can detect a female urinary tract infection much more effectively, Handley says, than a urine test.

Two studies showed that tracking eye movements during a physical exam can differentiate between inner ear problems and a stroke better than an initial MRI. MRIs and CT scans carry the additional danger of showing harmless abnormalities that could lead to unnecessary tests and complications.

The value of exams goes far deeper than diagnoses. "The physical exam is learning to find things, but it also is part of a ritual, part of a tradition — it's also a connection being built," Novan says.

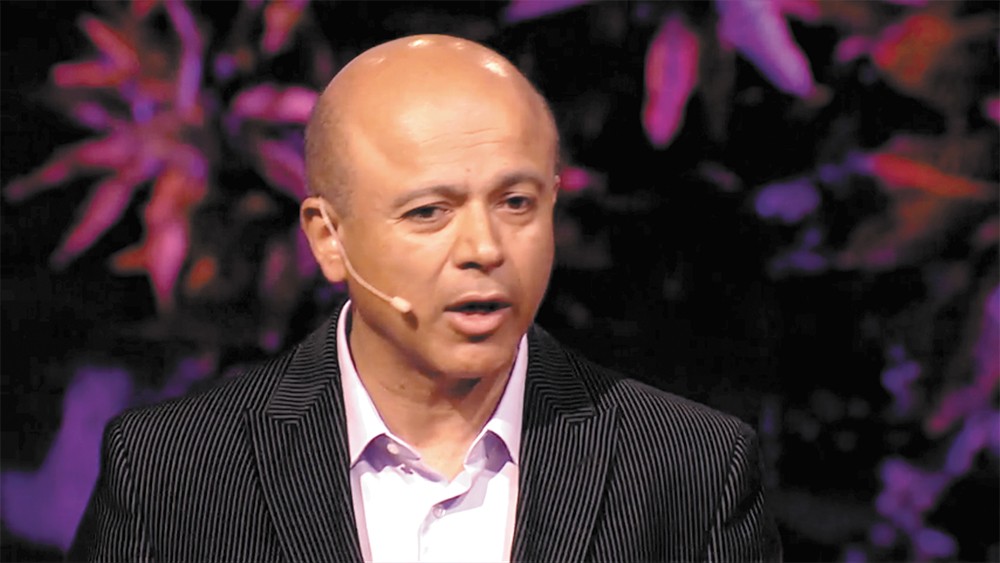

Standing before the TED talk stage, Verghese, the Stanford doctor, talks with a soft, multicultural blend of an accent. He tells of a woman who collapsed during a doctor's visit and was rushed into an MRI.

"The real tragedy was, she had been seen at four or five other health care institutions ... four or five opportunities to see the breast mass, to touch the breast mass, intervene at a much earlier stage than when we saw her," Verghese says. "This is not an unusual story."

In other words, she'd had plenty of tests, but had never received a physical exam that would have detected her breast cancer.

"We're losing a ritual that I believe is transformative, transcendent and is at the heart of the patient/physician relationship," Verghese says. "The ritual of one individual coming to another and telling you things they would not tell their preacher and rabbi, and incredibly, on top of that, disrobing and allowing touch. I would submit that that is a ritual of exceeding importance."

That intimacy, he argues, is more than diagnosis: It's forging a relationship.

The underlying problem: doctors have a very small amount of time for visits. Today, a visit of only 15 minutes is typical, according to Kaiser Health News. Some are even shorter, lasting less than four minutes.

When residents practiced their physical exam skills on Novan, he spotted bad habits.

"They're sometimes speeding things up and shortcutting and not doing things the right way. I had a resident examine me and listen to my heart and lungs through a shirt," Novan says. "The acoustics change when you do something like that."

The lack of primary care doctors, the influx of aging baby boomers and Obamacare's wave of newly insured patients means more pressure than ever to quickly diagnose, then move on. That's where doctors make errors. That's why they tend to interrupt patients' explanations.

"It might not be unusual for a patient to be interrupted within 18 seconds of being asked what's going on," Novan says.

The problem with interrupting, Novan says, is that the patient may be hesitant to share the fears and worries of themselves and their family regarding the illness.

"That's going to impact how they perceive their illness and how they respond," Novan says. A patient may come in for a cough, but have a deeper worry because their father died from cancer. That's an opportunity to listen to them, to address their concerns and quell their fears.

A good doctor can detect uncertainty or hesitancy — a patient may squirm or fidget or become uncomfortable. Then the doctor knows how to probe further, to try to get at what a patient is really feeling. "You can take brief notes, but you don't want to take word for word, because you'll miss seeing things," Novan says. "People will answer a question 'no.' But the way they answer it — the body language — will tell you there's something else behind it."

Not everyone is a traditionalist, of course, when it comes to the promise of medicine.

In an article on TechCrunch.com, Sun Microsystems co-founder Vinod Khosla argued in a 2012 article that that computerized algorithms, getting more adept all the time, could someday replace most of what primary care physicians do.

"If 90 percent of the time the doctor knows exactly the right kind of diagnosis from these very few and superficial inputs ... does it really require 10-plus years of intense education for every diagnostician?" Khosla wrote.

Today's medical algorithms are shoddy and easy to mock. But algorithms get better all the time, and Khosla greets this possibility with excitement.

"I doubt very much if within 10 to 15 years ... I won't be able to ask Siri's great, great grandchild (Version 9.0?) for an opinion far more accurate than the one I get today from the average physician," Khosla says. "Eventually, we won't need the average doctor and will have much better and cheaper care for 90 to 99 percent of our medical needs."

After all, Watson — that IBM computer that trounced superstar nerd Ken Jennings on Jeopardy! — now has software intended to help doctors comb through medical records to help make diagnoses. But that approach has genuine skeptics.

Verghese contrasts an oil painting from 1891, of a doctor at the bedside of a dying patient, with a picture of a crowd of modern doctors, in lab coats and ties, crowded around a laptop in a conference room.

"The patient in the bed has almost become an icon for the 'real' patient" he says. "The real patient often wonders 'Where is everyone? When are they going to come by and explain this to me? Who's in charge?'"

In other words, we have more tools than ever to diagnose medical conditions: The key is knowing when and where to use them. The invention of the screwdriver didn't make the hammer obsolete. All the tests and data and fancy equipment can't compensate, Novan says, for true personal interaction between doctor and patient.

"There's a quote by Francis Peabody," Novan says. "'The secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient.'" ♦

Tiny Patients

Giving a physical exam to a kid is a whole different challenge than giving one to an adult. Children can be more fidgety, more prone to tears and more unable to articulate exactly what's wrong.

Brooke Jordan, a nurse practitioner with Northwest Spokane Pediatrics, says she'll sometimes give kids a few tongue depressors or let them play with her stethoscope. She may play with them for a few moments before the physical exam begins — a way to get them to trust her. Some kids are clearly nervous. She'll let them hold the otoscope light into their ears.

"If they have a stuffed animal, we'll pretend to listen to the stuffed animal before we listen to them," Jordan says.

She'll check their immunization records. The questions she asks the parents go far beyond simple medical history. Are they wearing helmets when they're riding bikes? Life jackets when boating? Do they have the right booster seat or car seat? After all, she usually sees children before they develop problems that could affect them for the rest of their lives.

"One of the biggest things we focus on is the patient education," says Jordan. "I believe the preventative side is key to maintaining health."