William Schneck has examined at least a thousand crimes scenes in his decades-long career as a forensic scientist. The shock of seeing what horrors humans are capable of doesn’t go away. Neither does the gag reflex.

But some cases have stayed with him, haunting him every now and then. His father was a construction worker in Milwaukee. He remembers driving around the city with his father and how he used to point out projects he’d worked on. Now, as Schneck passes a certain street or recalls a certain town, he thinks: That’s where someone was shot. That’s where someone was murdered.

There was the woman in California who was stabbed in the heart. He never knew there were so many different types of Asian vegetables — bok choy, baby bok choy, napa cabbage — until he studied the contents of her stomach. There was the boy, maybe 10, who was kicked so many times in the abdomen that his breakfast — oatmeal with raisins — spilled out, staining a wall like a twisted Jackson Pollock.

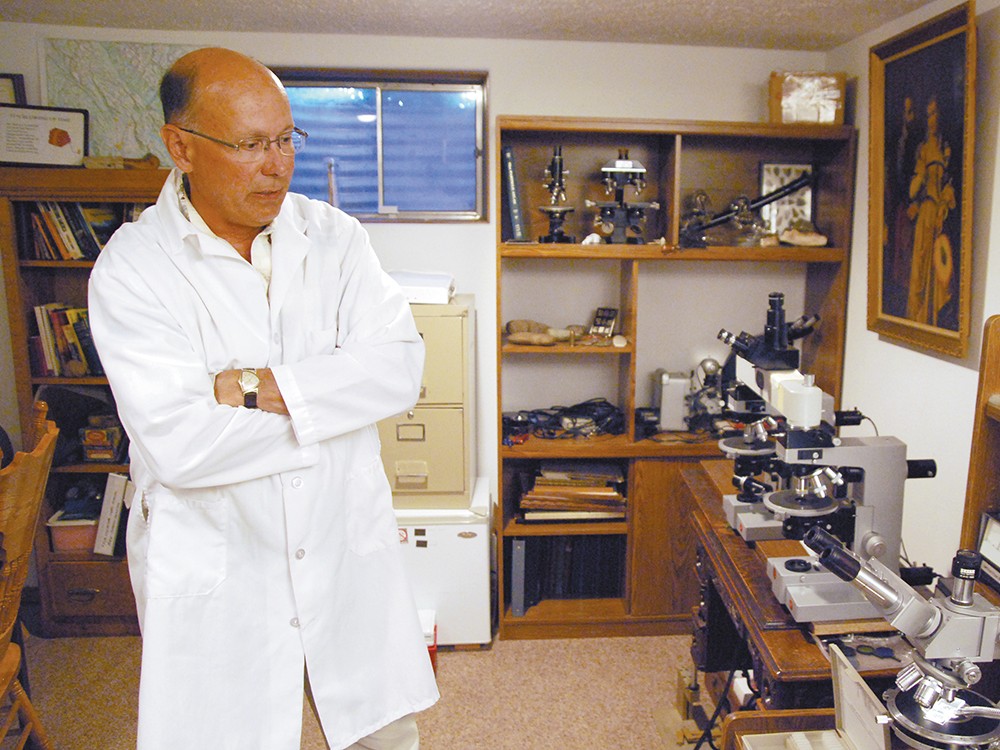

A geologist by training, he works full-time for the Washington State Patrol Crime Lab. On the side, he runs a forensic consulting business, Microvision Northwest, for out-of-state clients out of a makeshift lab in his basement. He specializes in reconstructing crime scenes and analyzing trace evidence, meaning microscopic particles, hairs, fibers, glass, paint, explosive materials, shoe and tire impressions and “gastro-contents,” which is the nice way of saying “vomit.”

People always ask Schneck about shows like CSI (rarely watches it) and Dexter (never seen it), and truthfully, they sort of creep him out. His stock answer is “We’re better looking; we make more money,” but that’s a joke, of course.

Guys like Schneck don’t carry guns. They’re not constantly pecking on keyboards and examining databases (though that is part of the job). Most of Schneck’s work involves tedious hours peering at slides under a high-powered polarized light microscope. On TV, crimes are solved in hours. Forensic investigations can take days, months or several years to complete. Forensic scientists don’t know everything about everything. But this is true: One little piece of evidence can change the outcome of a case.

Still, Schneck doesn’t have a personal stake in the crimes he examines; he’s just looking for answers to what happened.

“I’m not working for the prosecution. I’m not working for the defense. I’m searching for truth and justice,” he says. “Whatever it is to exonerate someone, or prove guilt or innocence.”

He finds his answers in unexpected places: A suspect’s hairs in a punched-out hollow of a wall; smeared paint on the bottom of a dead man’s boots that match the color of a suspect’s car; or traces of Malt-O-Meal Marshmallow Mateys in the bed of a pickup truck belonging to a father whose 11-year-old son didn’t show up for school that day.