This past spring, at the 60th Annual Northwest Anthropology Conference held on the WSU campus in Pullman, Dr. James Chatters offered a glimpse into just how rigorous the life of a professional old-school hunter could be. Dr. Chatters, currently associated with AMEC Earth and Environmental of Kirkland, has worked as an archaeologist on the Hanford Nuclear Reservation and taught as a professor of paleontology at Central Washington University in Ellensburg. He was the expert called in when the remains of Kennewick Man were discovered near the confluence of the Columbia and Snake Rivers in July of 1996. Chatters made the preliminary examination of the bones and sent off the samples for radiocarbon dating that came back with an age of around 9,400 years before the present, thus making Kennewick Man the oldest almost-complete skeleton known from our continent. Dr. Chatters remained on the scene during the long court case involving what to do with the bones known to Plateau tribal people as "The Ancient One," and, as a result of legal decisions, finally had an opportunity to study the remains in more detail.

Under carefully controlled conditions, Chatters closely examined distinct markings on Kennewick Man's limbs and joints to determine how the man might have acted while he was alive. "Musculoskeletal stress markings (MSM) are areas of bone overgrowth and bone loss resulting from stress on the skeletal musculature," Chatters writes. "The more habitual and loaded an activity, the more pronounced the markings." Anyone who works a trade over many years, from hoeing cotton to clicking a mouse, develops telltale patterns of MSM that can be seen in the areas where tendons and ligaments attach muscles to bone.

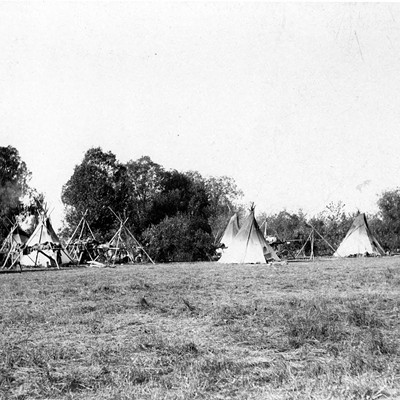

At the time of Kennewick Man, people living along the Columbia survived by hunting and gathering. Dr. Chatters reasoned that since the remains were found along the river, and since cast nets are known from archaeological sites from this period, the Ancient One may have worked as a fisherman. The act of casting a weighted net requires arms flung away from the body at shoulder height and from the inside out. This would leave very different bone marks than those of, say, an overhanded spear thrower.

Because the skeleton of Kennewick Man is almost complete, Chatters was able to lay out the bones and view every joint that would have been involved in such rigorous and repeated physical activities. What he found was an area of distinct bone overgrowth on the right shoulder joint that corresponded to overhand throwing. He also found MSM consistent with hard throws in the right elbow, and in the right wrist. In the left hip and knee he saw marks that could jibe with the deep leg drive necessary to finish off a throw. In addition, Chatters described a series of high rib fractures on the right side of the chest that had never healed properly, as if the bones in that area were continually wrenched apart by a throwing action. Dr. Chatters's conclusion was that Kennewick Man, the ancient hunter of the Plateau, killed his food with atlatl darts.

The atlatl marked a key innovation in the development of human hunting. Sometimes spelled atl-atl and usually pronounced more like ot lotl, it is a spear-throwing device that allowed a hunter to throw a weapon at a target with great force from an impressive distance. Atlatls have been recovered from archaeological sites on all inhabited continents and take many forms: The common element is a shaft about the length of a human forearm with a grip on one end and a catch, spur, cup or pin on the other. Hunters rested the butt of their spear against the catch, fingered the shaft of the spear parallel to the atlatl, and combined a wheel of the upper arm with a shift of body weight and flick of the wrist that finished in a powerful leg drive. If you have ever wielded a lacrosse stick, watched a surf caster throw a weighted hook impossibly far out to sea, or flipped off a springy diving board, you have experimented with the physics that provide an atlatl's powerful addition to a simple spear toss.

Atlatls begin to appear in the archaeological record around the end of the last ice age, when large mammals such as camels, giant ground sloths, mammoths and outsized bison roamed the Northern Hemisphere. In Europe, archaeologists have unearthed decorative atlatls that date to around 20,000 years before the present. Paleontologists who believe humans played an important role in the demise of the Ice Age megafauna attribute much of the early hunters' success to atlatls.

The MSM that Chatters noted around the joints of Kennewick Man are remarkably similar to the stress marks that occur today on the muscles and bones of baseball pitchers. The brute strength of an overhand fling, the stress on the elbow, and the deep leg drive are all consistent with professional hurlers. Most telling, perhaps, is that the final flick of the wrist so key to an atlatl throw corresponds directly to the awkward downward jerk of a breaking ball. Think of all those curves, sliders and split-fingered pitches, and the strain they put on a throwing arm. A quick perusal of any team's injury list, running through oblique tears, hip flexors, Tommy John elbow surgery, and especially the dreaded frays of a rotator cuff, were probably all twinges felt by the Ancient One.

Chatters found a chip in Kennewick Man's right shoulder joint broken out of the overgrown bone itself. That chip, those fractured ribs, and several other significant injuries (including a projectile point embedded in his right pelvis) indicate that this man was an older hunter who was near the end of his active life when he died. However it played out, the Ancient One had a long career, a hunter who developed his craft by working at it as a matter of life and death, over and over, one throw at a time.