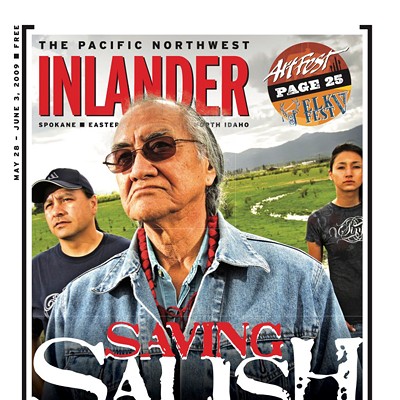

“Do you know, this is the largest gathering of Salish-speaking people in a hundred years?” Chris Parkin is standing near the doorway to a large meeting hall at Northern Quest Casino, and his excitement is so contagious that it hits you: The 321 people quietly gathering over breakfast here at the casino are from the same tribes and bands that gathered on the Spokane River every June for 10,000 years to share the bounty of leaping spring chinook.

Friday morning they cruised a buffet line for breakfast and coffee. Here they were with their plates: Spokane, Kalispel, Coeur d’Alene, Colville- Okanogan, Lakes.

Parkin, a former high school language teacher, is one of the organizers behind this Celebrating Salish conference. Though not an Indian, he helps design curriculums for the Kalispel tribe and others striving to hold onto their ancient languages. The conference is designed so regional tribes can share concerns and success stories.

The lighting is dim in the big room. People are moving slow at 8 o’clock. Many had been up late for a Salish karaoke contest the night efore. The buzz of conversation is down at a soft level. But the conversation, that’s the thing. People are greeting each other in Salish. You hear a lot of “Xest skweskwst:” Good morning.

The gathering last week was the third Celebrating Salish conference, which is growing so fast that it outstripped its meeting space each of its first two years.

The Kalispel tribe offered to host the first conference in 2009 because, frankly, things were looking grim.

The salmon don’t make it to the falls any more. The runs of the fabled “June hogs” ended in 1939, during the construction of Grand Coulee Dam. The people are gone, too, moved to reservations scattered from here to northwestern Montana. And the language is hanging by a thread.

The Inlander first met Jessie Fountain two years ago, when the graceful young Kalispel tribal member shared one of her deepest fears. What if, by the time she becomes old, no one speaks the language? What if, at her funeral service, no one remembers the hymns in Salish?

“The scary thing is, who will bury me? Who will sing for me when I die?” she said then.

This very real concern spurred her, she says, to learn to speak Q’lispe (kull-luh-speh), her tribal dialect of Salish.

Fountain’s drive propelled her deep into the language. She progressed so quickly that Kalispel language director J.R. Bluff tapped her to be among his first wave of teachers.

Friday, when we saw Fountain again, we learned she is now teaching an adult immersion class, and is helping launch the new Language Nest, a one-hour Salish-language preschool program on the rez.

But the big news: She’s five months pregnant with her first child and is taking the battle to save her language to a new level.

“I am going to raise my son in the language. I am not going to speak any English to him,” she says. “This is why I am investing everything I know, everything I have into this.”

And she’s not alone.

LaRae Wiley, who traces her lineage to the Lakes Band, now part of the Colville Confederated Tribes, is raising a 3-year-old granddaughter completely in Nselxcin (n-selk-cheen), the Lakes dialect of Salish.

She believes that her granddaughter, Fountain’s unborn son and the children of other young Native women represent a reconnecting of amily and tribal history. These are children who can close the gap, heal the deep cut from the days when language was often forcibly stripped away.

Neither Fountain nor Wiley sees this as a rejection of the dominant culture. It’s not an either/or.

“Obviously, these children will be bilingual. We want the best of Native culture and the best of domestic culture so they can navigate both worlds,” Wiley says.

In fact, at last week’s conference, there were sessions by young Indians from Montana who created Salish Street, modeled on Sesame Street. “They have the whole thing: puppets, numbers, songs, the alphabet,” Wiley says.

And there was the Salish karaoke contest, to show that the language isn’t just homework. It’s a chance to laugh and be goofy.

Wiley is excited. “It’s just poetic. It’s … oh man! I’m looking forward to the day when my granddaughter and Jessie’s son can speak to each other in the language.”

There’s a word for that. “Nmusls.” Hope.