When his time comes, Jason Corcoran weaves through the buzzing Saturday night mob of yammering girls in tank tops and men with tall cans of bad beer. He seems to notice no one as he walks toward the stage and, likewise, no one seems to notice him either.

At the show, another local rapper’s album release party this past February, Corcoran is just an opener — a guy standing in the way of the person the rowdy crowd paid to see. Two girls in the corner, entrenched in a frantic, cackling conversation, don’t even turn when he takes the mic. In front of the stage, another girl grinds her ass into the thigh of her male friend as Corcoran chants into the microphone. “If you could start over now,” he repeats, “you could be just like us.” It’s hard to tell who is just hearing the beat and who is listening to the words.

And it’s also tough to tell if anyone here realizes that this somewhat nasally white rapper onstage has arguably created this scene for them.

Better known to crowds as Freetime Synthetic, Corcoran has been making hip-hop relevant in Spokane for the past 15 years, throwing hip-hop shows when there weren’t any, rapping when few others were, encouraging other rappers to keep trying.

As the founder of local hip-hop collective Bad Penmanship, he’s assembled a scene of serious, thinking man’s rappers that is unique to the Northwest.

Corcoran is nonplussed, though, when asked if he ever rapped to get noticed. He did it because it was just what he had always done.

“Me and my little brother always [rhymed] doing chores or on the ski lift. Walking to school. We’d take turns going. Or we’d go back and forth,” he says. “We’d do that all the time, to pass the time.”

Flying Spiders frontman and longtime Spokane emcee Isamu Jordan says he remembers seeing Corcoran perform in the mid-’90s with then-popular local band Upper Class Racket. He was blown away by what he heard: a punk band with two emcees rapping over the top. He says he’s continued to be impressed by Corcoran.

“He’s forwarding the direction of Spokane culture in a hip-hop context in a super-progressive, creative way,” Jordan says. “[His music is] the real experience of the human condition of a regular person in Spokane.”

“His CD is the one that’s in my car right now. There’s Wu-Tang, there’s Radiohead, there’s Freetime Synthetic.”

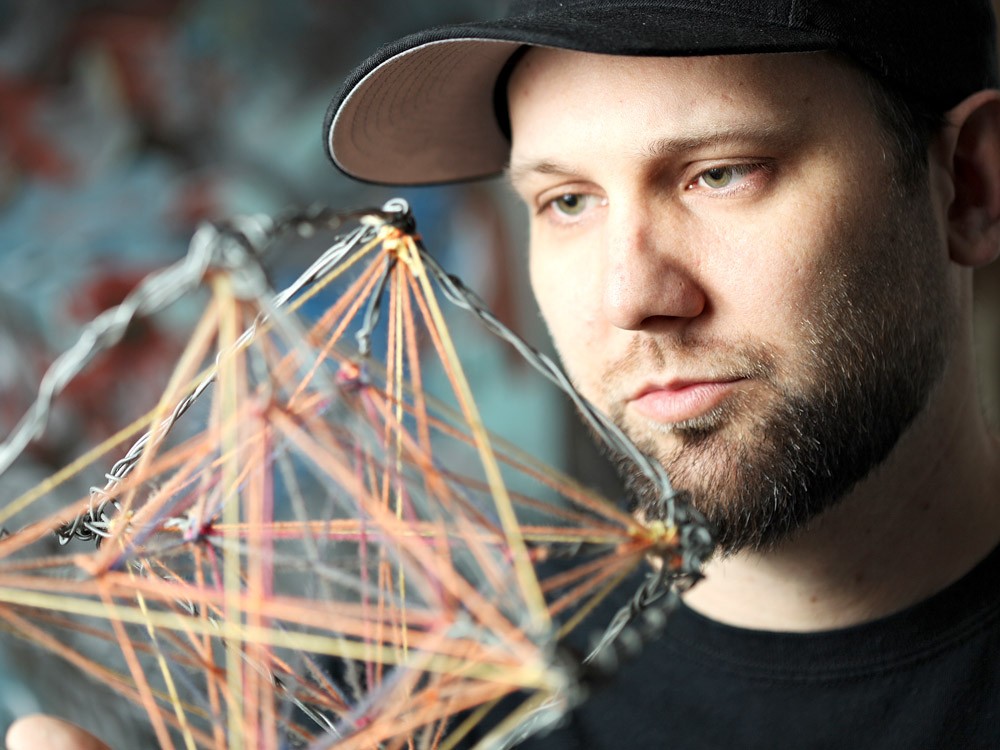

When Corcoran, 35, talks about why he writes the bouncing, twisted hip-hop he writes, or paints the dreamy, melting landscapes that he paints, he explains it in even-tempered paragraphs. There is no one reason — only philosophies and truisms.

A lot has changed in the 15 years since Corcoran first picked up a mic. He’s older, wiser. He has a son who is now almost as old as the scene he helped create.

Today he sits below three canvas paintings hanging at the Saranac Public House — works that he painted live in front of First Friday onlookers in early March. On the table in front of him is a stack of yellow-and-black posters for his upcoming show. He drew those, too.

The paintings, the flyers — they’re all reflective of Corcoran’s nonstop need to create. That’s what he was programmed to do.

“I never stopped coloring when everybody else stopped coloring,” he says, smiling.

It’s something he honed in the hallways of Shadle Park High School, where he’d sit with his art class and make sketches of the long rows of lockers that lined the halls. Other students would stop and watch them draw.

“I think I unintentionally got used to zoning people out, and that made it easier to do the live stuff that I do,” he recalls.

After high school, he left Spokane for the Minneapolis College of Art and Design. That’s where he learned that, despite his need to create, he didn’t need to be verified by others to continue doing it. And it’s also where he realized how much he could achieve back in his hometown.

Today he works in a warehouse. It’s a job he can do while listening to his songs on headphones all day. As he works, he memorizes the lines that will eventually become his songs.

“I pretty much dwell on [my music] all day, every day. Either my problems in my life and things I need to do for my family, or the next thing I’m doing with music and art,” he says. “If I’m gonna do a regular job, I have to be able to at least listen to music.”

Corcoran admits that standing on a stage and painting in front of an audience still doesn’t come naturally to him. He says when he started rapping with Upper Class Racket, he would stand with his back to the crowd. Even now, he seems to hide under his dark ball hat.

But putting himself out there for public consideration, he says, is simply a necessary way for him to untie the knots in his own head.

“I’m not having a conversation with you on the stage,” he says. “If I’m saying something where it sounds like I’m telling someone what to do or saying ‘you,’ I’m definitely talking to myself from a higher standpoint or from a future standpoint. Or, like, talking to my son.”

Unlike some artists who grow to hate their old work, Corcoran says everything he’s done is truly a reflection of himself; today, yesterday and tomorrow — it’s all inside of him.

That steadfast resolve has made Corcoran an authority in Northwest hip-hop, most notably through Bad Penmanship, a loose collective of local hip-hop artists.

“Synthetic has made tireless contributions to the local hip-hop scene, not only through the genius of his craft but also by supporting other artists and promoting the music scene,” says Jaeda Glasgow, who often performs with Corcoran.

Whereas much rap music is grounded in an I’m-better-than-you ethos, Corcoran avoids that mentality altogether. His sound is different, lacking the pomp and machismo prevalent in rap.

“This isn’t a joke to me,” he says. “Every time I write a verse, I am 100 percent trying to write the best one I’ve ever written in my life … the best combination of syllables, the trickiest clever thing I’ve said.”

And he also makes great strides to ensure that the emotion in his music is pure. That means Corcoran will only collaborate with DJs that he knows personally.

“I’ve only ever used [beats] from people that lived in my city,” he says, stressing the importance in shared experience. “They’ve gone through the seasons and know what Riverfront Park looks like and breathed the air.”

It’s a process that helps keep him making new music, year in and year out.

“Everyone else just sees it as like ‘You’re doing it this long and never got on a label?’ ... Some people think I should be disappointed by it, but it was never even a goal.”

He’s achieved many goals he once had with his music. And he has what so many others don’t: a body of work that is uniquely his.

“If all of my songs are together, I feel like you would definitely know who I was if I was long gone.”

The Best of Freetime Synthetic with DJ Stone Tobey, Black Ceiling, K. Clifton, Fat Arm, Outlet, Octoninjitsu, Sales Wagon and Fresh Children • Fri, April 6, at 8 pm • Mootsy’s • $5 • 21+ • reverbnation.com/freetimesynthetic • (838-1570)