Beethoven had been almost completely deaf for nearly a decade when his Ninth Symphony debuted in Vienna in 1824. It was the famously tormented composer's last finished symphony, now regarded as a milestone in humankind's long history of music, but not a note of the performance — nor, for that matter, a single handclap of the audience's rapturous applause — ever reached his ears.

And yet, with Friedrich Schiller's poem "Ode to Joy" on their lips, a multitude of singers and soloists celebrate life, hope and brotherhood in the symphony's rousing choral finale. Though he had more than his share of reasons to wallow in bitterness and self-pity, Beethoven chose to end his masterpiece with an outpouring of affirmation and aspiration.

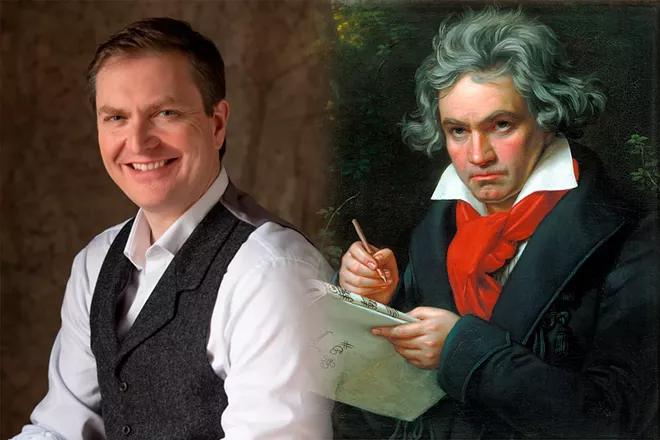

"It's a wonderful choice of music to perform at this time of year because it ends with this astonishing message of hope and unity. It's not just about this hope for a great future. It's also a piece that talks about when we all unite together, we can really experience joy and move humanity forward. And I think it's a message we all need reminding of on an annual basis," says James Lowe, the Spokane Symphony's music director.

In Spokane, performing Beethoven's Ninth as one year yields to the next is a tradition that dates back to the arrival of Lowe's predecessor, Eckart Preu, who himself imported the tradition from his native Germany. There, as well as in Japan, New Year's Eve performances of the Ninth Symphony have been common since around the time of World War I, largely because of the work's sense of uplift and renewal rather than its ease of execution.

"Although it's kind of a standard repertoire piece, it's not an easy piece at all. There's a lot of moving parts. With the last movement, it's not so much that there's a few tricky corners but that it's all corner. That said, it's the best piece to close out an old year and start a new one. It sets up all the best intentions."

But as with any tradition, every iteration has to tread the fine line between evoking the past and avoiding the staleness of overfamiliarity. And while Lowe has led orchestras in this work seven or eight times by his own recollection, this is his first time conducting the New Year's Eve Ninth in Spokane since he assumed his current role in 2019. That naturally creates its own set of challenges and opportunities.

"I had coffee with Eckart recently, and he said, laughingly, 'Good luck.' Every conductor has their own thoughts and angles on this piece, so I'm interested to see how that comes across. What does the orchestra want to do naturally, and how does that differ from my own interpretation? Any time an orchestra has a repertoire piece that they've played a lot, you always come across this feeling that they have baked-in instincts about how certain corners work."

Rather than being an irreconcilable source of friction, that creative push and pull could end up striking the crucial sweet spot between novelty and legacy.

"I don't like to go into any orchestra with really fixed ideas of how it's going to be and have them bend to my will. I like to make music with any orchestra that I work with," Lowe says, contrasting that collaborative sentiment with the infamous anecdotes of "Toscanini screaming at his double bassist."

"So, for me, that's the approach. We'll mold this piece together, and the message that it ends with is so appropriate for that. I think making music through love and enjoyment gets far better results."

Whatever might be different under Lowe's baton, one aspect that remains decidedly unchanged is that the Ninth Symphony is alone on the program. Unlike standard Masterworks concerts, there are no supplemental or juxtapositional pieces. The event begins with the symphony's "pretty tragic" first movement and ends with the effusive fourth.

"This does stand on its own two feet so well," Lowe says. "It's not as long as a normal concert would be, but it's still a good hour's worth of music, so you feel full afterwards," with the added bonus that "the performance ends at a time when you can still go out and party and do what you want."

Within that relatively short amount of time, says Lowe, it's possible to unplug from the distractions of modern life and experience the transformative effects of great music.

"This is a piece that starts out with real darkness and despair. But ... the whole point of the last movement is dismissing all of this darkness and saying, 'No, let's unite together and experience the joy of hope.' You'll go in one person and come out another, and that's such a great gift to give yourself and others at the end of a year. And I have to say, this particular year has been a bit of a humdinger." ♦

New Year's Eve: Beethoven's Ninth • Fri, Dec. 31 at 7:30 pm • $25–$62 • Martin Woldson Theater at The Fox • 1001 W. Sprague Ave. • spokanesymphony.org • 509-624-1200