From the outside, you wouldn't even know Ben Joyce's art studio exists. It's tucked inside the warehouse space of a nondescript one-story building that houses a flooring company, at a Spokane intersection where industrial and residential meet. It's a rectangular room built within another, and it doesn't look much more glamorous than any other cement box dedicated to storing linoleum and tile.

Step around some of the landlord's inventory and through a padlocked sliding door into Joyce's workspace — and it still doesn't exactly look like Ground Control for a skyrocketing art empire. But that's exactly what it is. There aren't even windows in this room full of in-progress paintings that capture landscapes from points across the globe, as well as, increasingly, the eyes and dollars of art collectors.

For visual artists, the quest for a unique style typically comes with much personal struggle, several false starts and years of schooling. Along the way, if they're lucky, they might hit on an approach to call their own. And there are still no guarantees anyone will care.

Joyce navigated the search for his own visual style for much of his 37 years, "always trying to find something a little different than somebody else." And when he found it, creating mixed-media paintings from an aerial view in a style he calls "Abstract Topophilia," he discovered that a lot of people cared. And a lot of those people wanted to buy a piece.

Collectors as far away as London have commissioned paintings from Joyce, while art lovers at fairs and festivals across the country have swooped on the bird's-eye representations of their communities. Closer to home, you can find large-scale pieces, signed simply "ben," prominently displayed in the Gonzaga University Jepson Center, in the lobby of the Spokane Convention Center Exhibit Hall, and in homes and offices across Spokane and Coeur d'Alene.

While some might dismiss them as simply elaborate, exaggerated maps, there's no denying the skill Joyce brings to his pieces. The finished paintings are a mash-up of everything from gels, tars, cement and burlap to different types of paint, from oil to acrylic and watercolor. He bristles a bit at the "map-like" description — "from my perspective, the only thing in common with maps is that they're from aerial perspectives" — but the mild-mannered artist recognizes that his commercial popularity is largely out of his paint-flecked hands.

"I love that people recognize that it's my work," Joyce says. "But I guarantee you that the reason people love it is because it's a piece of them. It's just one of those [ways] that people connect with their place."

And Joyce is totally fine with that. The search for his style was largely based on his desire to find a way to paint that would help people connect to their place — their literal, physical space — in the world. It's an idea he started playing with nearly two decades ago, as a Gonzaga student studying in Florence, Italy, and traveling around Europe. Seeing the pride people there had in their homes and towns stuck with him when he returned to the States and worked toward starting an art career.

You might think that achieving the level of success Joyce already has would be the end of a feel-good story, that of a Spokane artist done good. But commercial success doesn't always equate to creative satisfaction and can lead to an array of new obstacles and questions about the future.

How much work is too much work? What's the perfect work/life balance? Can the family finances count on continued popularity of his art? These are stresses the weekend plein air hobbyist doesn't have to worry about.

"Art is a very interesting business to be in, and everybody is different," Joyce says. "I have a family to support, so there's layers to that." Among them is the fact his middle child, a daughter named Nora, has 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, a condition with more than 180 wildly divergent symptoms. "You have your passion to create and paint, but you have a responsibility to yourself and your family.

"You're working on both the passion and professional side of things. How do you combine business and creativity? It's one of those equations that has taken time to figure out."

The passion for place

Joyce's first sale nearly eight years ago was the result of a dare from his wife, Erin. With relatives visiting Spokane, she challenged him to put one of his paintings on the wall of a downtown restaurant where they were having a party. Dare accepted, he lugged the four-by-eight-foot piece to the party and put it on display. He left it behind that night, and got a call a few days later from Chuck Wilbert, a local contractor who'd discovered it while dining with his wife.

"He said they loved the colors, they loved the composition, loved that it's not square. He said, 'Man, there's something so familiar about it!'" Joyce recalls. Then it dawned on Wilbert that it wasn't simply a large piece of modern art, full of dramatic angles and bright colors. It was Spokane, viewed from above, complete with railroad tracks, the interstate, Riverfront Park. As soon as he realized he was looking at his lifelong home, Wilbert had just one more thing to say to Joyce: "What do you want for it, because we have to have it."

"It was so strikingly different from anything we had ever seen before," Wilbert says. "That's what's really attractive to us. I guess it's more of a memory of places you've been, places you've visited, had fun at. So you buy it kind of as a memory of a certain good time."

The conversations Joyce has with collectors now, years later, almost always revolve around the places they love, rather than the style he's going to use on their paintings.

"I've been fortunate that I have a style that really connects with people," Joyce says, noting the satisfaction he gets in hearing families' oral histories of different places through his work. "If you're standing in Sausalito and looking at a piece of the San Francisco Bay, you have a connection to that piece. Whether you love it or hate it. There's not many art forms that can say that."

His secret warehouse space is at least the third studio Joyce has had since demand for his work started to heat up about six years ago, and even though it was basically built for him and he pays his rent in paintings instead of cash, it's not hard to imagine him outgrowing it. Sure, it's just Ben and his brother Jason working inside, but when you start landing large-scale public installations, you might soon need your own warehouse-sized space. In winning the assignment to create a large work at the Spokane Convention Center, Joyce and his brother had to put it together from 18 smaller pieces.

"He's become a pretty popular young man," says Kevin Twohig, executive director of the Spokane Public Facilities District. In addition to Joyce, Twohig has helped select art for the convention center from local artists like Melissa Cole and Steve Adams. "Frankly, we take a lot of pride in the minor push we've been able to give these artists along their careers. And Ben would be solidly in that mold. There's a lot of passion, a lot of creativity, and yet no b.s. That's the nice thing about working with local artists — the community is very grounded."

Karen Mobley was the longtime director of Spokane's city arts department and is now a consultant who worked on the convention center project. She remembers Joyce calling about a decade ago to request a meeting after he'd been rejected from some public art opportunity. He wasn't calling to berate her — he wanted advice on how to write better proposals for those opportunities in the future.

"I was really impressed, because ... he's the kind of guy who doesn't put his head in his hands and say, 'Oh, woe is me, I didn't get the job,'" Mobley says. "He's more like, 'OK, let's figure this out. What can I do better?' There's something pretty special about having that kind of attitude, that I can grab the world by the tail and figure it out."

Drive meets vision

Ambition has always been part of the equation for Joyce, who grew up outside Los Angeles in a town called Acton, where his parents own a small newspaper chain. He was the fifth of eight children, a "diplomat and listener" among combative siblings in a house where the parents' entrepreneurial spirit left the kids far from spoiled. Joyce describes his childhood as "a kind of grind-it-out-and-survive-type life," but even with financial strain omnipresent, "going to college wasn't a question," it was a requirement, and one the kids were excited to fulfill.

Ambition took him to architecture school and a brief career as a college football quarterback at Southwestern College in San Diego before he transferred to focus on fine arts at Gonzaga, the school that four of the family's five boys attended.

Ambition led him to quit jobs as a broke newlywed to focus on his art. Ambition led him to apply to small art shows in the Inland Northwest, and after selling pieces at Art on the Green in Coeur d'Alene or ArtFest in Spokane, to keep making more and expanding his work to landscapes outside the Inland Northwest.

Ambition led him to convince his brother Jason, a fellow Gonzaga grad, to move back to Spokane and help on the artistic side (with his woodworking skills) and the business side (keeping up with demand, traveling to shows together). Mobley describes Jason as an integral part of his brother's work, saying "Ben couldn't be Ben without the support of his family, because he's doing these big things."

"I've always thought of this on an international level," Joyce says. "We're talking about an international form of art. There isn't a place on Earth that isn't a potential piece for me. So the people who connected with it around here, I thought, 'Let's see if that connection [extends beyond Spokane].' In the back of my mind I knew it would. I just needed people to see it."

While Joyce has always been confident in his abilities — C average in school be damned — he recognizes that his own life experiences, and those of the collectors he talks to about their favorite lakes, rivers and cities, infuse his work with a depth now that wasn't always there. It certainly wasn't when he woke Erin in the middle of the night in their small post-collegiate apartment more than a decade ago to tell her he'd figured out his vision for a new style of painting: a "landscape that one could travel through."

"How can you see what's behind those hills? What's off in the distance? What's behind you?" Joyce says. "I was feeling claustrophobic in these [traditional] landscapes."

Going global

Mobley, for one, has seen obvious growth in Joyce's skills, both with a paintbrush and in traversing the obstacles for young artists trying to make their mark. He's a "pretty driven, focused" guy, she says, and all the work he's done as he's gained an audience has just made him a better artist.

"You see somebody who is working very hard, and they kind of pass over a certain place and all of the sudden, there's a kind of maturity that comes with a lot of work. That's very cool to watch," Mobley says. "As he gets more experienced, I think he's getting more sophisticated with the paint application and the understanding of the color."

Applying and being accepted to the highly competitive Sausalito Art Festival on his first try five years ago gave Joyce's profile the kind of boost that selling his first piece to Wilbert did for his confidence. Getting into Sausalito opened doors to major shows in places like Chicago and Miami.

That first trip to Sausalito will always stick out for Joyce because of the group of guys "who looked like they were coming out of a fraternity or watching a ballgame." They turned out to be employees of Google Geo, home to Google Earth and Google Maps, and they liked his work so much they sold their boss on installing some of Joyce's landscapes around the office. Five years later, Joyce is a regular at Google, rotating new pieces in each year or so. The style appealed so much to Google VP and Google Earth inventor Brian McClendon that he hired Joyce to make three pieces for his house that pay homage to his hometown of Lawrence, Kansas, which serves, incidentally, as the default center point of Google Earth.

"Obviously, I'm deeply into maps, so it fit well," McClendon says of first seeing Joyce's work at his office. He was most struck by Joyce's "subject matter, which is unusual, and the style and materials." Of the four artists who have done geo-related exhibits at Google in the past five years, only Joyce has enjoyed more than one, McClendon adds, and his pieces enhance the experience of Google's workers.

"It sort of reminds people that what we're working on is so inspiring in other dimensions that people will create great art about their location," McClendon says. "We are all about reproducing the world exactly and precisely, and having this more flexible presentation is kind of fun."

This way lies the future

As Joyce's name and the popularity of his "Abstract Topophilia" style continue to spread across the art world — quite literally; one recent commission was for a billionaire's private 737 — Joyce and his brother have to constantly evaluate how to keep up with demand.

"There's no way I can keep up with the pace of creating originals," Joyce says. "To a point, you're always trying to create this distance of time, like, when does that day come when you're not as hot as you are now?"

Given the heat on Joyce's vision right now, he and Jason are asking themselves a lot of questions. Do they need to keep attending the big art shows in faraway places? Would it be worthwhile to open a small gallery somewhere close to home, like Seattle, where the family travels regularly for Nora's medical appointments? Should they consider making prints, or putting Joyce's images on calendars, coffee mugs and T-shirts?

One potential outlet is already in the works, a clothing line called LYP — short for "Love Your Place. Live Your Passion." Still in its infancy, Joyce considers LYP a potential means of getting the message of his art onto new products without confusing collectors of his original works.

Some have suggested Joyce leave Spokane in the interest of growing his art business. But he has his own connection to this place, forged through his years in college, where he met his wife, and his love of the outdoors.

More important, Seattle is one of two U.S. cities with a clinic specializing in a holistic approach to treating kids with Nora's condition. That means a lot of trips back and forth for doctors appointments, but it also means that 8-year-old Ava, 6-year-old Nora and their 4-year-old brother Cyrus can keep living in Spokane, where they are fourth generation natives on Erin's side of the family.

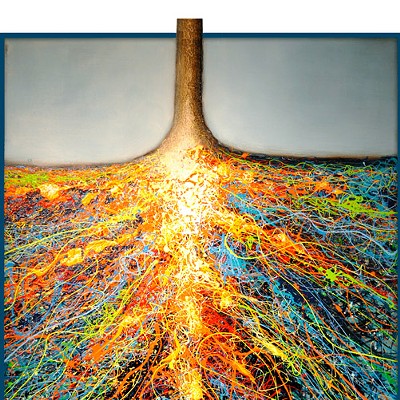

The experience of getting to know Nora's ailment inspired Joyce to create a remarkable painting, one that falls outside the Abstract Topophilia style into something more personal.

The painting, called "Nora," is a kaleidoscopic view of a tree's root system, with the trunk of the tree just barely visible at the top.

Joyce says he wanted to "represent the life and energy that creates the beauty we see. We see the tree," which to Joyce represents the vivacious, beautiful little girl bounding around the house and backyard with Ava and Cyrus as her parents chat with a guest.

Over the course of an hour or so on a sunny Saturday morning, the kids will take turns joining the conversation to climb on their dad, who shares a quick cuddle before gently sending them off so he can focus on the task at hand. Later, he'll join them in their playroom he graffitied with their names.

"The specialists and doctors who work with Nora, they see the roots," he continues. "They see the beauty we don't see. I can see my daughter in a way through their eyes, not just my own."

Nora and "Nora" live together in the family's home in the Ponderosa Ridge neighborhood. The painting might be a look at a different style Joyce could pursue in the future, away from Abstract Topophilia.

At the very least, it's a striking image of a place no one will ever find on a map. ♦