It only takes a second for everything to change.

In 2018, Benjamin Gedeon was walking back to work after a late afternoon lunch break. It's a short, half-mile walk between the Panera Bread in north Spokane and Royals Cannabis, where Gedeon worked as a budtender.

But there's a nasty obstacle: Division Street.

The intersection of Division and Rhoades Avenue has seven lanes of north-south traffic, three in either direction and a center turn lane. There's a crosswalk, but no traffic signals.

That afternoon, Gedeon made it halfway across the street without any issues. He paused at the pedestrian refuge, an island of relative safety in the middle of roaring traffic, to wait for a break in the platoon of cars heading southbound. A truck in the lane closest to him and a car on the outside lane both stopped and their drivers made eye contact with Gedeon. He ventured out into the street.

But there was a Honda Element in the middle lane. He couldn't see it, and the motorist, a college student at Whitworth University, didn't see him. She would later tell police her phone was in her back pocket, and that she was going slower than the posted speed limit of 35 mph.

But the car weighs more than 3,500 pounds — more than a black rhinoceros, among the heaviest land mammals on Earth.

She hit him. His body was thrown 51 feet.

Gedeon survived, barely. Doctors had to remove part of his skull. Gedeon, who was 22 at the time, underwent months of recovery, but he still struggles with emotional and cognitive problems, disturbed sleep and depression.

Gedeon sued the driver who hit him and the city of Spokane itself, alleging that its failure to build a safe pedestrian crossing led to his life-changing injuries. His lawyers pointed to the intersection's history of collisions — including one death — and argued that the city was well aware of the intersection's flaws. It had, in fact, commissioned a study in 2008 that said as much. Last month, the city settled the lawsuit with Gedeon for $3.1 million.

Gedeon's story isn't unique. Since 2014, nearly 1,500 pedestrians and more than 750 people on bicycles have been struck by cars in Spokane County. At least 305 of those collisions resulted in serious injuries. Seventy-eight of the people who were hit died.

So in some ways, Gedeon is lucky. He wasn't one of those 78 people. But he's still a victim — and the intersection at Division and Rhoades isn't the city's only dangerous crossing.

SUVS, SMARTPHONES AND COVID

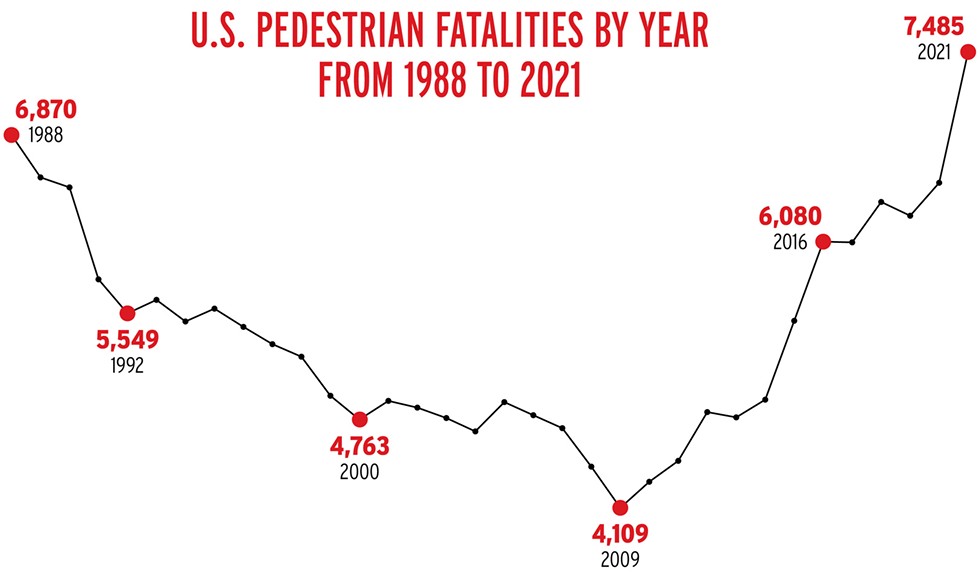

For a while, it seemed like the U.S. was making progress.

After peaking in the early 1980s, the number of people getting struck and killed by drivers steadily declined for decades. But in 2009, something flipped, and the numbers started going back up. Researchers have pointed to a number of factors, like increasingly larger cars or the introduction of smartphones. The deaths kept rising, and by 2019, the number of annual pedestrian fatalities was back to what it was in the 1980s.

And then the pandemic hit, and everything got dramatically worse.

"Things just exploded," says Rhonda Kae Young, a professor at Gonzaga's civil engineering department.

In 2021, nearly 7,500 pedestrians were killed by cars nationwide — the highest number in four decades. Preliminary data from last year indicates that the trend has only worsened. U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg described it as a "national crisis."

In Spokane County, 15 pedestrians were killed in 2021, the highest number on record since 2014, the earliest available local data.

It's not just pedestrians. Drivers are also dying in record numbers. But when you look at the total number of deaths, pedestrians are vastly overrepresented. Between 2010 and 2020, pedestrian deaths increased by 54 percent, while all other traffic deaths increased by just 13 percent.

Numbers for last year are still rough, as death certificates for people who were struck by cars and later died at hospitals are still coming in. But the preliminary data isn't looking great, and it appears another record year will be on the books.

There's no single explanation for the dramatic uptick in deaths during the pandemic. People were driving less, and fewer cars on the road should lead to fewer deaths, but researchers now suspect that the emptier roads encouraged people to drive faster.

There are other possible factors, but they're really all just educated guesses, says Mark McKechnie, a spokesperson with the Washington State Traffic Safety Commission. The pandemic was a stressful, destabilizing time, and there's evidence to suggest that the people started engaging in all sorts of risky behaviors: gambling, drinking, fighting and — crucially — aggressive driving.

Also, in Washington the number of crashes involving drivers under the influence of two or more substances also spiked. McKechnie notes that law enforcement eased up on traffic enforcement during the pandemic.

Regardless of what caused the recent spike, it's clear that the problem is decades in the making. And while human decision making certainly plays a role, we're still beholden to the physical, built environments through which we move.

When a car hits someone, there's a tendency to assign blame. Was the pedestrian wearing dark clothes at night? Were they crossing without looking? Was the driver on their phone?

But questions like that overlook the broader problem, says Gonzaga's Young. In recent decades, researchers have moved away from the word "accident," because it assigns fault to an individual, instead of examining the larger structural changes that could prevent something like that from happening again.

Those structural changes don't have to happen all at once — many pedestrian safety improvements are relatively quick and simple, Young says.

Curb bumpouts, for example, extend sidewalks near crossings into the street, making it so pedestrians aren't shielded from view by parked cars. Bollards — those vertical posts that act as a protective barrier between vehicles and pedestrian-only streets, for example — have a similar effect, and are even easier to implement, Young says. Little plastic "armadillo" lane dividers can be installed to separate cars from bike lanes and act as little speed bumps to keep drivers in their lane.

Pedestrian hybrid beacons, a flashing yellow-then-red traffic signal that is triggered by the push of a button designed for midblock crossings at uncontrolled intersections, are more costly. The city has installed a number of them around town — on Grand Boulevard near Manito Park, for instance — and is putting three of them on Division this year, for a total cost of $1 million.

They're generally pretty effective, Young says. Studies from the U.S. Department of Transportation's Federal Highway Administration show that they can reduce collisions involving pedestrians by up to 55 percent.

Each year, Young takes her students to the Netherlands, which has for decades served as a sort of near-perfect vision of pedestrian- and bike-centered streets. Its rate of pedestrian fatalities is among the lowest in the world. It's shocking how bad America's looks in comparison.

Young says it all comes down to a philosophy of cooperation and a "streets are for everyone" approach. People on bikes, on foot and behind the wheel all share the roads equally. A person driving a car near bicyclists is likely to be more cautious because they also ride a bike regularly and have a shared interest in keeping the roads safe.

That's not the case in America.

"I think if you talk to people here about the multimodal aspect, I think they would probably talk about conflict and hostility," Young says. "There's a fundamentally different approach."

In the Netherlands, that philosophy translates to massive investments in infrastructure that prioritizes pedestrians and cyclists.

Other northern European countries, like Denmark, have similar approaches to traffic planning. When former City Council President Ben Stuckart traveled to Copenhagen in 2018, he was inspired to introduce an ordinance to formally adopt Spokane's Pedestrian Master Plan into the city's municipal code and ensure that the city prioritizes "transportation systems that protect and serve the pedestrian first."

It seemed like an easy enough goal.

MONEY, MONEY, MONEY

Four years after his ordinance passed, Stuckart is still skeptical of the city's commitment to prioritize pedestrian safety.

"Little tiny things that I was always frustrated with that they wouldn't do, I still don't see those getting done," Stuckart says.

Breean Beggs, the current City Council president, says it's probably time for the council to revisit the topic.

"Frankly, even though we passed the law that Ben proposed, we haven't asked for a report on it," Beggs says. "Like, are they really doing it?"

Money is always a problem. The city's pedestrian master plan acknowledges as much, warning that the many programs and solutions it proposes require funding, and that "there will likely never be enough money to do everything."

When constituents come to Beggs with concerns about unsafe intersections, he generally tells them to go to their neighborhood council so the problems can be addressed through the city's Neighborhood Traffic Calming Program. The program began in 2010, and uses revenue from the city's speeding and red light cameras to fund traffic calming projects based on neighborhood input.

The program has been really effective, Beggs says, and gives neighbors a direct voice in the process. There are $3.6 million worth of traffic calming projects slated for this construction season — mainly in the form of rapid flashing beacons, curb extensions that bump out into the street, and crosswalks with center refuge islands. People can help decide future projects at three town halls scheduled at the downtown Spokane Public Library on May 16, 17 and 18.

Spokane will spend $27 million on basic road maintenance this year, and just $6 million on sidewalk and pedestrian projects.

tweet this

But the program isn't without its drawbacks. It operates on four-year cycles, which means projects chosen this year will be installed gradually over coming construction seasons. It's a great long-term vision, says City Council member Zack Zappone, but the cycle makes it difficult to react quickly when new hot spots are identified.

"If there's an issue that comes up this year, you couldn't see any change until 2028," Zappone says.

If that sounds like too long to wait, Beggs says your second-best option is to go to the city directly and try to make the case that the intersection is dangerous and that someone is going to get sued if they don't do something quickly.

But the voices of pedestrians worried about something that might happen are often drowned out by the voices of drivers worried about something that definitely happens every winter and spring. Potholes, Beggs says, put the city under a lot of pressure.

"We know if we don't pave Riverside we're going to hear about it," Beggs says. "That's politics."

The city has roughly $27 million budgeted for grind and overlay projects to replace aging street surfaces this construction season. Total sidewalk and pedestrian crossing projects total around $6 million, not counting the projects funded by the Traffic Calming Program.

Funding pedestrian infrastructure projects can be really complicated, with a maze of federal and state grants that all have different criteria.

For example, a pedestrian hybrid beacon the city is installing on Nevada Street and Joseph Avenue this year at the cost of $800,000 is funded by the state through the Safe Routes to School program. The state program is paying for the project because of the crossing's proximity to Whitman Elementary School, as well as its history of collisions, busy traffic and neighborhood demographics.

A similar hybrid beacon slated for the intersection of Greene Street and Carlisle Avenue is funded by the state's bicycle and pedestrian program, based on its history of collisions, traffic volumes and speeds, transit use, and connectivity to the Children of the Sun Trail, which runs near the unfinished north-south freeway.

The series of pedestrian beacons along Division are funded through a federal safety grant, also due to the street's history of collisions.

Zappone and Beggs credit city staff for aggressively pursuing grant opportunities. But the problem with the whole process, Zappone says, is that applications for competitive grants are more likely to be successful if you can show that some horrible incident happened at the intersection.

"So it's not preventative in any way," Zappone says.

When it comes to pedestrian safety, city spokesperson Kirstin Davis says it's important to take a step back and look at the big picture. The city has, in many areas, made genuine progress. Jason Lien, a transportation planner with the Spokane Regional Transportation Council, cites the Garland and Perry districts as two examples of neighborhoods that have seen significant improvements through lower speed limits, curb bump outs, and buffers between the sidewalk and the street.

Anthony Gill, who runs the urbanist website Spokane Rising, says the city's traffic calming work near Gonzaga's campus — specifically the roundabout and the Cincinnati Greenway — have also been really effective.

"That's a good example of a place where concentrated investments have really helped make the neighborhood a better place to walk around," Gill says.

But other areas still need a lot of work. Crash data from the state transportation department shows a number of Spokane intersections that continue to see a high number of pedestrian collisions year after year.

The worst intersection appears to be the one at Browne Street and Pacific Avenue on the eastern edge of downtown. Since 2013, 11 pedestrians and three bicyclists have been hit by cars there. Five of those collisions resulted in serious injuries, and one resulted in a death. The area sees a lot of foot traffic, and Browne is a one-way, four-lane road where cars often drive fast. One block south, the intersection of Second Avenue and Browne is also a hotspot — with 12 crashes and one death since 2013.

Davis says city staff are aware of the collision patterns at the intersection, and that the city recently received funding to build a greenway bike route along Pacific that will include new traffic signals at the intersection. Design should start late this year. The city has also received funding for pedestrian hybrid beacons at collision hot spots like Regal Street and Thurston Avenue, and Nevada and Cozza Drive. Those should be built by 2025, Davis says.

And then there's Division.

"It's a brave soul that wants to cross," Young laughs.

A LETHAL GAME OF FROGGER

Today, the intersection where Gedeon was hit is still really scary.

Five years after the collision and 15 years after the study found that the intersection is dangerous, the crossing still lacks any form of pedestrian beacon. The only signal to drivers that someone might cross is a white crosswalk and a pair of yellow signs with stick figures on them, as if to remind drivers that humans exist. The nearest crosswalk with a light is more than a thousand feet away.

The sidewalk is narrow, and you can feel gusts of air as each car whips by. The posted speed limit, 35 mph, doesn't feel like much when you're driving, but it's a whole other story when you're on foot, standing less than a meter away from traffic.

As you wait for a break in cars so you can cross — sometimes for a minute or more — you can't help but feel like you're in the wrong place, and unwelcome. The cars have somewhere to be, and you're getting in their way. This wasn't built for you.

When a break in traffic finally comes, it's almost impossible to walk across the street at a normal pace. The gap in cars might only last a few seconds, and everything about the street's design screams — run, run, run! — like it's a game of Frogger. You inevitably find yourself breaking into an awkward speed-walk/jog as you begin to cross.

After making it across the first three lanes, there's an island of relative safety — three lanes of traffic moving at a lethal pace on either side of you. You wait, and the problem that almost took Gedeon's life immediately becomes clear: if a car in the lane closest to you stops to let you pass, it blocks your view of the lanes farthest from you. If there's a car coming, you can't see them and they can't see you.

The massive size of modern cars doesn't exactly help. The pickup truck driver who stopped in the inside lane to let Gedeon cross acknowledged as much in a statement for the lawsuit, saying that he drives a "good size vehicle" and blocks "a lot of views."

There's also social pressure. An ever-growing line of cars is now stopped to wait for you, and it feels like you have just seconds to make a decision. You hope there aren't any cars in the other lanes, and venture out into the street.

Researchers have a word for that: double jeopardy.

"The pedestrian feels compelled to go because now they're delaying someone, and so their decision process gets a lot more hurried," Young says. "And then that stopped car is shielding the car that's coming up behind it from seeing what the car is stopped for."

It's a really vulnerable situation for pedestrians, Young says. The best thing to do is to stop in front of the first car and then peer over to check the middle lane — but human nature kicks in, and that fast-paced walk/jog game of Frogger begins.

Things will be different this fall, when the city plans to install a flashing pedestrian beacon there. Davis, with the city, says the project is funded with a federal safety grant the city applied for in March 2020, before the lawsuit was filed. Being able to show the history of collisions helped secure the grant.

Cindy Schwartz, one of several lawyers who represented Gedeon in his lawsuit against the city, says Gedeon is thrilled about the news. He still struggles with memory issues, trauma, a seizure disorder and a lifetime on medication because of the crash. People at his former workplace have told him about close calls, and he's glad they'll be out of danger soon, Schwartz says.

"He's very happy that they're going to do that, because he's worried about other people getting hurt as he did," Schwartz says. "Maybe not as bad, but any kind of injury can affect your life."

Division as a whole has long been a hot spot for pedestrian collisions. It's a major transit corridor that puts cars at the forefront. Humans are an afterthought.

"It's a terrible experience, completely miserable," says Gill, with Spokane Rising.

The entire street is slated for an overhaul, one day. If and when the north-south freeway is finished and Division's traffic is diverted to it. In December, the Spokane City Council voted in support of a plan to transform the street. The plan, outlined in a multiyear study called DivisionConnects, would include a rapid bus route along the street, along with other pedestrian improvements.

The plan is a step in the right direction, Gill says, but it doesn't solve the fundamental problem: Division is simply too wide for pedestrians to safely cross.

In a perfect world — with political willpower and highway-level funding — Gill says he'd be interested in seeing Division completely transformed.

There's a similarly troubled transit corridor called Aurora Avenue in Seattle, where a group has proposed a radical transformation that would see parts of the street shrink down from seven to just one lane for cars in each direction. Other parts of the street would be repurposed for buses, bikes and maybe even a light rail. A true pedestrian utopia.

"It would be fundamentally rethinking the street with safety in mind first, as opposed to, 'What safety retrofits can we make to Division?'" Gill says. "It's a different mindset."

Gill acknowledges that a radical transformation like that isn't likely anytime soon. But it's nice to imagine. ♦

SPOKANE'S TROUBLED INTERSECTIONS FROM 2013 to 2021

PACIFIC AND BROWNE

14 people hit by drivers

(Ten pedestrians and three cyclists hit; one pedestrian death)

SECOND AND BROWNE

12 people hit by drivers

(Nine pedestrians and two cyclists hit; one pedestrian death)

BROADWAY AND MONROE

8 people hit by drivers

(Seven pedestrians and one cyclist hit)

WELLESLEY AND CRESTLINE

12 people hit by drivers

(Seven pedestrians and four cyclists hit; one pedestrian death)

INDIANA AND DIVISION

9 people hit by drivers

(Five pedestrians and four cyclists hit)

RHOADES AND DIVISION

8 people hit by drivers

(Seven pedestrians hit; one pedestrian death)