After Hayden homeowner Jeremy Morris accused his neighborhood association of anti-Christian bigotry when they tried to stop his massive Christmas display, he won a victory in federal court. (You can read about the entire saga in this week's cover story.)

But none of these articles reference the other time Jeremy Morris called people anti-Christian bigots.

Last year, Morris dramatically made that same accusation against Coeur d'Alene School Board trustee Tom Hearn. But, in this case, the conflict wasn't over Christmas. It was over an issue even more fraught: the symbols of the Confederacy.

It's an incident that gives more insight into Morris and the contours of the culture war in North Idaho.

It started with a Facebook thread last year, three days after the white supremacists marched in Charlottesville to oppose the removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee.

Coeur d'Alene attorney Charles Lempesis posted a Facebook comment where he sarcastically suggested burning books after just tearing down statues.

"As soon as we get all the statues down we need to start burning books," Lempesis snarks. "Our founding fathers were slave owners and it's probably high time to demo the Jefferson Memorial and the Washington Monument... We cannot erase history, rather we must learn from it."

Morris, meanwhile, is a history buff who keeps Civil War memorabilia in his office. A Civil War chess set. A print of William Trego's The Rescue of the Colors. He pops up in the thread as well and agrees with Lempesis' sentiment.

"Our country is full of ignorant people and socialist wackos," Morris commented. "Why have we let them do this?"

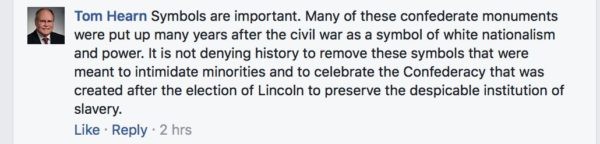

But Hearn had a different take.

Hearn has plenty of historians who would agree with him: As Ohio State University's Sarah Gardner writes, the installation of many "Confederate monuments coincided with the rise of Jim Crow, a legal, political, and cultural system that denied African Americans their place in the American polity."

Hearn wasn't proposing anything specific. There wasn't a Confederate symbol in North Idaho he was targeting. He wasn't calling for a change in the Coeur d'Alene school district's curriculum.

But Morris was furious. Hearn says Morris, in Facebook comments (some since deleted), called him a “fascistic, disgusting excuse for a human being," an “ignorant buffoon,” a "disgrace" and “Chairman Mao Tse-Hearn."

Instead, they encourage him to "sign up for public comment at any regular board meeting," but caution him that public commentary was intended to be used to comment on district business,

But Morris cries censorship. He calls his allies together for a protest:

Who will join me for a mock-book burning? Let us ask Mr. Hearn which American slave-owning Founding Father that our own Board Trustee, book-burner Tom, would have us scrub from our children's curriculum. Jefferson? Washington? Which of their monuments need to come down? Which American patriots are off-limits for our school children?

He goes as far as comparing the Coeur d'Alene School Board to 9/11 hijackers, saying that both groups "hate America."

To Morris, approving of the removal of Confederate flags and statues is comparable to burning books. He and a friend cobble together a crude bonfire prop, attaching several conservative history books to the logs.

And then he props it outside the School Board meeting, waving an American flag beside his book-burning bonfire prop and proclaiming that “we have Bolsheviks that have taken over the School Board.”

He says that's why the Coeur d'Alene School Board didn't want to have political party IDs attached to the elections.

"Every one of them voted for Obama, and they would have voted for Marx and Lenin if they were on the ballot. That's a fact," Morris says at his protest. "What they really are is

And then Morris labels Hearn with the same scarlet letter as he slapped on his homeowners association: anti-Christian bigot.

To Hearn, that label is ridiculous. He's a Christian himself, he points out.

But Morris references a 2014 Facebook post, where Hearn had questioned why “fringe political and religious groups” kept moving to Coeur d’Alene.

"Asking why they have moved here," Morris yells during his demonstration. "Talking about Christians. He's a bigot! He's the worst bigot of them all! What if I said that about African-Americans or Mexicans, how quickly would the [Kootenai County Task Force on Human Relations] be at the house investigating my family. Why is it different and OK for a board member to talk about Christians that way?"

But Hearn isn't talking about all Christians. In fact, that Facebook post is linking to a specific Coeur d'Alene Press story about a rally hosted by Coeur d'Alene pastor Warren Campbell, and featuring Kalispell, Montana, pastor Chuck Baldwin as the keynote speaker.

Both pastors are unabashed about politics and are both

Morris himself has a pretty close connection to the Redoubt movement: The Bible study he attends was started by Don Bradway, the guy featured in

But despite the founder of the Redoubt movement specifically condemning racism and welcoming Orthodox Jews into its movement, strains of anti-semitism and neo-Confederacy have crept in.

As the Inlander has documented at length, Campbell has given sermons praising the Confederacy, defending slavery and arguing the Holocaust was exaggerated.

And Baldwin's ideology goes beyond just neo-Confederacy. Here's a sermon from this September where Baldwin spouts anti-Semitic 9/11 conspiracy theories.

If you read this book you'll understand why this is happening. You’ll understand that it was not 19 Muslim terrorists that masterminded the events of 9/11. You’ll understand that, for the most part, with a lot of help from various factions inside our own government — yes, you heard me say it, ‘from inside our own government’ — this was purely, wholly and mostly a Mossad operation.In that same sermon, he says "anyone who's half-way awake knows that Zionists control our mainstream media and entertainment industries, but they also control and censor much of our internet as well."

Morris doesn't see himself as a racist or an anti-Semite. Far from it. He says that he's half -Jewish. He argues that Hearn is the one distorting his faith.

"As a Christian, I know that Isaiah 5:20 says, 'Woe unto them that call evil good and good evil; that put darkness for light and light for darkness,'" he writes to Hearn on Facebook.

Campbell, Baldwin and Morris have all been featured guests on a podcast called Radio Free Redoubt, hosted at a site called Redoubt News.

It was the Redoubt News website that captured Morris's School Board protest on video. ("When a School Board trustee wants to erase history, what is a parent to do?" the Redoubt News article begins.)

Hearn isn't actually at the School Board meeting the night that Morris holds his protest. But in his speech in front of the fake book-burning bonfire, Morris says that's appropriate.

He accuses Hearn of effectively smearing the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), the organization that put up large numbers of the Confederate memorials.

"They can't defend themselves. They're all dead. They died 100 years ago," Morris says. "I am now hosting a protest, just like the 80-year-old women that he castigated, stereotyped, and lumped together in this prejudicial disgusting way, calling them all 'white nationalists.' They can't defend themselves, well, he can't either. Good luck, Mr. Hearn. I hope you can see this on the internet."

Morris calls the UDC "the first real feminist organization in the country."

"Women who were what? Marching at the time with the Klan? I don't think so!" Morris says. "They were marching for the memorials they erected after doing knitting groups raising funds for their dead husbands."

But as historian Karen Cox writes in Dixie's Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture, there were plenty of connections between the Ku Klux Klan and the UDC.

She notes that the "UDC officially recognized the Klan for helping to restore Southern home rule and white supremacy" and that the "first generation of the United Daughters of the Confederacy regarded the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) of Reconstruction as the South’s redeemer."

"Most UDC members revered the first KKK, and the organization was often included in their articles on the Lost Cause," she writes.

The UDC Catechism for Children, for example, taught children that slaves had been treated “with great kindness and care in nearly all cases, a cruel master being rare.”

Morris acknowledges there may have been some racists in the UDC, but Cox's book goes much further, arguing white supremacy was a fundamental part of the UDC's mission. Their goal was to rewrite history.

"The Daughters’ idealization of white supremacy as an Old South custom that should remain intact is critical to understanding the racist implications of their work," Cox writes.

Mildred Rutherford, the UDC's official historian-general in the early 1900s, argued that “negro suffrage was a crime against the white people of the South.” She argued that ex-slaves should remain faithful to their former masters. That slaves “were the happiest set of people on the face of the globe,” that slavery had had a "civilizing power" on Africans, and was part of the “the greatest missionary and educational endeavors that the world has ever known.”

The UDC would visit schools and angrily protest if they were using textbooks that were too critical of the Confederacy and push to get the curriculum changed and portraits of Robert E. Lee hung in the

And it worked.

"By the 1920s most Southern states had adopted pro-Confederate textbooks," Cox writes. It remained that way for 50 years, she continues, noting that generations of black children were taught from "Lost Cause" textbooks "which included assertions about the inferiority of their race."

Back at the School Board meeting in 2017, the Coeur d'Alene board gives Morris three minutes to talk. But Morris still accuses the board of trying to censor him.

“I’m going to speak. And if it's civil disobedience, so be it," Morris says. "We all know about sitting at lunch counters. Well, that’s revered today. That’s respected. People say that was good civil

When black civil rights protestors sat at the whites-only lunch counters in North Carolina, they were heckled by whites who carried small Confederate battle flags, by people who were educated under a Lost Cause history revised and sanitized over decades through the efforts of groups like the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

It's those protesters and their tactics of disobedience that Morris alludes to in his comments to the board.

As Morris's speech stretches beyond the allocated three minutes, School Board president Casey Morrisroe asks Morris to stop speaking. But Morris keeps speaking. Morrisroe gavels the meeting into recess. And Morris keeps speaking.

"How many of you agree with censoring history!?” Morris demands as the audience stands up and begins to file out.

Morris puts his whole speech on YouTube. He caps off the video with photos of his mock book-burning bonfire, set to the music of the "Battle Hymn of the Republic" — a Union fight song.

Hearn says he has never attacked Morris publicly and has tried not to make political disagreements personal. But it's clear how Hearn feels.

“We are not on each other’s Christmas card list,” Hearn jokes to the Inlander.