Who wouldn't be excited about $10,000? But it wasn't the money as much as the project itself that had the Spokane Arts Grant Awards (SAGA) 2018 panel curious and excited. Columbia Fire & Iron was looking to build a mobile blacksmith program, conjuring a vision from olden days: The tang of metal and dust in the air. The steady plink, plink, plink of hammering over and over until it's time to reheat the metal in a grumbling forge. More hammering, a rush of air as the forge is fed, and finally the hiss of metal meeting water, like a baptismal font anointing the iron as a finished piece.

"Fifty-one-year-old me is almost as excited at the prospect of [mobile blacksmithing] existing as 11-year-old me would have been, just short of hopping up and down making googly cartoon eyes and howling," wrote Nate Huston, one of six committee members who awarded the grant to the nonprofit created by several local blacksmiths to promote the art form.

David Kailey, who created Morgan-Jade Ironworks and serves as CF&I's vice president, knows just how Huston feels. Kailey says he was bitten by the blacksmith bug as a youngster at a shop run by one of his father's friends.

Although Kailey grew up tinkering with metal, he also knew he lacked the formal instruction necessary to take his interest in metalworking to the next level. Enter Steve McGrew, a Spokane-based blacksmith with 15 years experience and a successful company, Incandescent Ironworks.

"Steve has been a phenomenal mentor," says Kailey, who scraped together $350 to take McGrew's introductory class in 2011, saved more than $1,000 for an anvil, then started doing events with McGrew and another blacksmith, Quailside Forge's John Huffstutter.

The trio eventually incorporated into Columbia Fire & Iron in 2013, although each continues to run his own business. In addition to the blacksmiths, the CF&I board includes Mallory Battista, a local visual artist who added blacksmithing to her repertoire after seeing McGrew demonstrate at the Spokane Interstate Fair.

Battista, who runs the group's website and does the marketing, was instrumental in preparing the SAGA grant, says Kailey. The $10,000 will enable CF&I to purchase six forges, 12 anvils, three post vises — it holds the hot iron while the smith works on it — more hand tools, metal and a trailer capable of handling an 8,000-pound load.

"We can roll in, roll everything out on the ground and set up in half an hour," says Kailey of their mobile operation, which CF&I hopes to bring to schools, youth organizations, businesses and other interested groups throughout the region. "As long as we have dirt that's reasonably flat, we can set up."

CF&I does several types of events, including demonstrations at the North Spokane Library and at Emerson-Garfield Farmers Market, where they'll be appearing every Friday through the summer starting on June 7, says Battista. They also do classes under the CF&I name, led by any of the three blacksmiths at his respective facility, making such things as latches, knives and hammers.

A third type of event known as a "hammer-in" is part demonstration and part hands-on learning opportunity with hot metal: from heating it in the forge, to hammering and bending it into shape over the anvil, to finishing it. In order to cover the cost of required individual liability insurance, CF&I charges a nominal fee, which in turn allows members to attend any of their hammer-in events throughout the year.

For the past two years, CF&I has held hammer-ins at Kailey's Spokane shop. One year, they got 85-90 people showing up over the two-day event, says Kailey, prompting them to change the format to four-hour sessions, 24 students a time, including youngsters. "If they're too young to forge with hot metal, they learn to forge with a specialized clay," says Kailey. Otherwise, the only requirement is they've got to be able to swing a hammer.

Contrary to what people may believe, he says, blacksmithing doesn't require big muscles. It's hot, dirty, physical work, he says, but the hammer they use is only 2-3 pounds. In fact, when people find out he's a blacksmith, says Kailey, they're surprised he doesn't have big, muscly arms.

"It's not a size game," he says. ♦

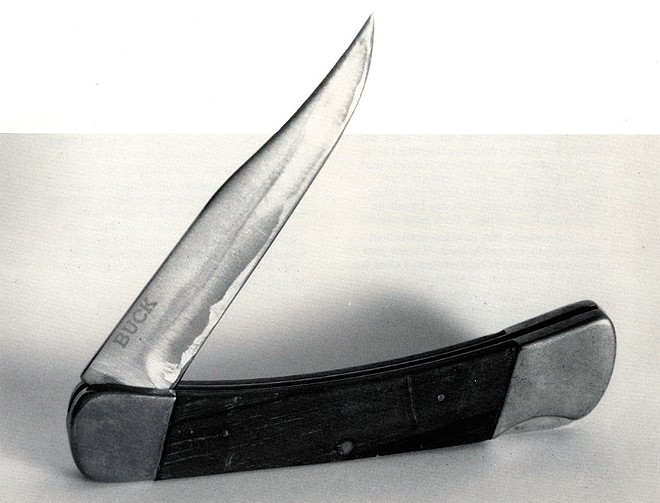

KNIFE MAKING TRADITION ON DISPLAY AT BUCK KNIVES MUSEUM

Call to schedule a tour of Buck Knives' Post Falls, Idaho, facility and you'll see how technology is used to design and manufacture their knives, yet it's tradition on display in the building's entryway. A painting hanging above the fireplace inside the lobby, for example, depicts founder Hoyt Buck in 1902 when he first apprenticed with a Kansas blacksmith.

Several walls are covered in historical photos and vintage advertisements from the company's 74-year history. Nearby, a stairway climbs to the Buck Knife Museum: an evolving display of knives, knife-making tools, advertising materials and other ephemera from 1945 onward, when Hoyt's son Al Buck joined his father in creating H. H. Buck and Son.

Joe Houser, who has been with the company 34 years, points out significant knives, many with original packaging. The popular 1960s Buck Model 110 Folding Hunter still has the original $16 price tag, but it would sell now for as much as $2,000, says Houser.

Other cases feature custom knives: collaborations with Harley-Davidson, military and tactical knives like one of the 300,000 M9 bayonets they produced for the U.S. Army, and beautifully wrought knives from their custom shop, which closed in 1992. Another case is filled with knives by David Yellowhorse, who would remove the inlay from Buck knives and replace it with semi-precious stones.

There's also an old Rockwell metal hardness tester, a pedal-powered grinding stone, and two gargantuan mastodon tusks the company opted not to incorporate into knife handles. Rounding out the collection are two anvils that would be perfectly at home in a blacksmith shop. They may or may not have been used by Hoyt, says Houser.