When Lara Strandberg graduated from Gonzaga Law School in 2009, she left with a rock-solid resume. On top of her diploma, she had professional paralegal experience and a paralegal degree. Yet, she knew, thanks to the recession, it may take her time to find a job at a law firm.

She didn’t know it would take nearly three years.

“I sent out hundreds and hundreds of resumes and letters,” Strandberg says. “I couldn’t even get an interview.”

In the meantime, she temped as a receptionist for a construction company. She went into solo practice, but only made $5,000 for an entire year.

“I was probably clinically depressed,” Strandberg says. “I had no direction where I was going to go. I felt like I’d wasted a heck of a lot of my family’s money.”

Last March she was finally hired as a personal injury attorney, but her struggles highlight the crisis that’s gripped both law school graduates and administrators: “There’s too much supply for the demand that’s out there,” Strandberg says.

In 2009, the American Bar Association fired off an official warning: Students expecting their $100,000 debts to be quickly washed away with six-figure salaries were likely mistaken. The cost of school was rising and “well-paying jobs [were] in short supply.”

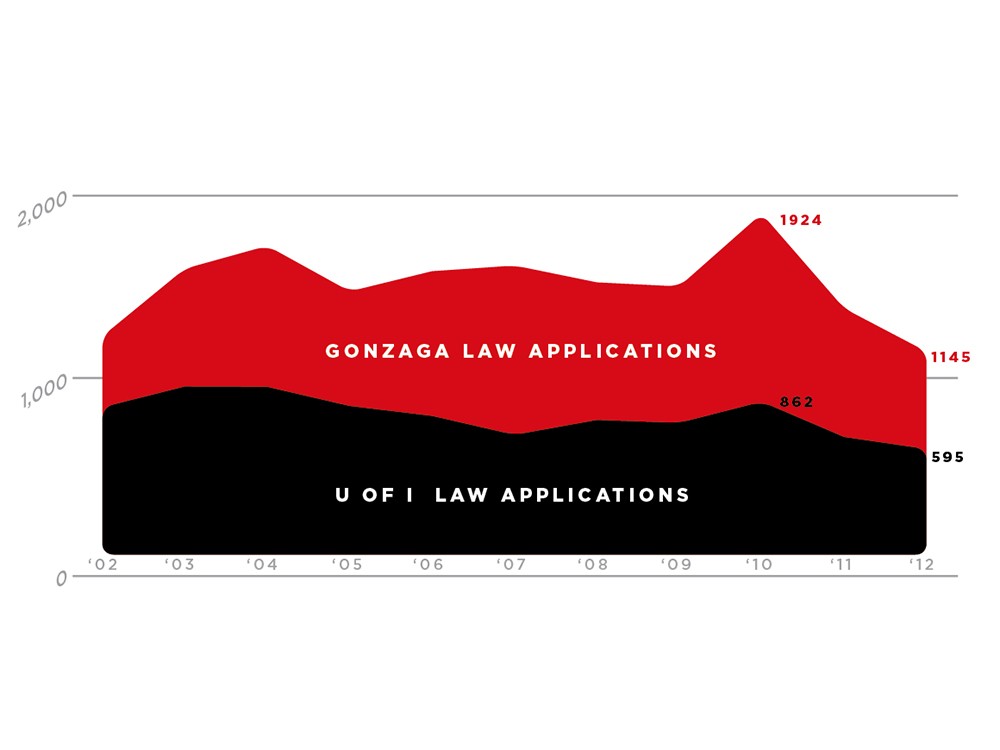

Gonzaga and the University of Idaho both fell victim to a national trend: Barely more than half the class of 2011 was employed in a long-term full-time job requiring a bar credential nine months after graduation. Prospective students took notice, and applications to law schools have plummeted.

Law school’s loudest critics come from inside the academy: Law professors like University of Colorado-Boulder’s Paul Campos lead a chorus of critics. “For many law students today, law school ends up being an economic tragedy and an intellectual farce,” Campos writes in his book, Don’t Go to Law School (Unless). “The tragedy is that every year, tens of thousands of bright, talented young people, full of energy, ambition and hope, discover that their legal educations have left them saddled with life-altering debts, and no realistic way of paying them off.”

Technology and recession, he writes, transformed the legal world: The Internet made searching for case law easier; outsourcing made reviewing documents cheaper; state budget cuts made government lawyer jobs scarcer. Most students in the bottom half of their first year law class, he writes, would actually be better off dropping out.

A flood of news reports trumpeting the dangers of law school have had an impact. Law school applications fell nearly 25 percent nationwide in the past two years. The University of Idaho and Gonzaga had to weather the blow.

“Every law dean has to make a decision,” Gonzaga Law School Dean Jane Korn says. Do they lower acceptance standards to fill the seats, or lower admission numbers and weather the financial blow? Gonzaga cut admissions. To compensate, it had to also cut travel budgets and freeze salaries.

Korn, and her University of Idaho counterpart, Don Burnett, paint a more nuanced picture than the national media’s dire landscape. Burnett says that, compared to many other professions, lawyers have a lower unemployment rate. Korn says most Gonzaga grads eventually do find jobs — they just may have to wait longer, try harder and be more flexible.

“A lot of times we’ll have a job and a student doesn’t want to go work there,” Korn says. “There are good paying jobs in Alaska. There might be good jobs in Yakima.”

Lucrative jobs in huge firms may be disappearing, but underserved populations remain. One solo-practitioner Korn knows tried to find someone to take over his practice, but nobody wanted to move to his small town.

“I think philosophically we still need to think about society’s need for those lawyers who aren’t going to make a lot of money,” says Gonzaga clinical law professor George Critchlow. “Society needs public defenders and prosecutors and city attorneys and legal aid lawyers.”

But the sheer weight of debt also constrains law students. A year and half after graduating, University of Idaho student Saundra Richartz managed to find a job as a deputy prosecutor in Stevens County. But with $35,000 in debt from Whitworth University and $160,000 from Idaho — not to mention credit card debt — she lives with her mother. Even if she wanted to go back to work at her old diner job, she couldn’t afford it.

“I needed to make at least $45,000-$55,000 a year to make a dent,” Richartz says.

The American Bar Association cites an estimate that the average student needs a $65,000 salary to compensate the typical law school debt. It’s one reason why schools like the University of Idaho are trying to keep their costs comparatively low.

University of Idaho, too, has cut admissions. Yet Burnett, the dean, stood in front of the state’s Joint Finance-Appropriations Committee last week to ask for money to continue expanding the school.

His request would cost Idaho $400,000 and would add a second year and about 10 students annually to the law school’s Boise program.

Burnett has faced the should-we-really-be-adding-more-lawyers question before.

“In Idaho, in the most recent year, only about 26 percent of the persons who were admitted to the bar came from the University of Idaho,” Burnett says. “We are a net importer of legal talent.”

Idaho has the 49th lowest number of lawyers-per-person, yet that difference hasn’t made it easier for University of Idaho graduates to quickly land lawyer jobs. Their figures are as bad as the rest of the nation. And soon, those graduates may have to compete for jobs with those from University of Concordia’s new law school in Boise. In its first year, the private nonprofit enrolled 74 students.

The expansion isn’t primarily about enrollment, Burnett says. “This is a student quality and student opportunity move,” Burnett says. Law students would be closer to Idaho’s government and businesses hub, closer to internships and clerkships that can become jobs.

University of Idaho and Gonzaga have started to adjust to the new legal market, focusing more on practical clinical law experience, legal writing and pro bono work.

Gonzaga’s Career Services turned into the Center for Professional Development — becoming less about resumes, more about networking. “I don’t know how many emails I send out a week to talk to the alumni,” Powers says. For basketball-oblivious students, she even recently sent out 11 talking points (“Yes, David Stockton is John Stockton’s son...”) to use when interviewers ask “How ‘bout them Zags?”

She places students in internships and nonprofits and encourages them to volunteer while finding work. Brian Ream, a Gonzaga student graduating this fall, says his internship with Leibow McKean, an intellectual property firm in Seattle, won him a tentative job offer.

“There are other people that did the same thing I did. Get an internship and turn it into a job offer,” Ream says. “If you’re not in the top 25 percent, the top 15 percent [of the class], you’ll need a connection to get a job.”