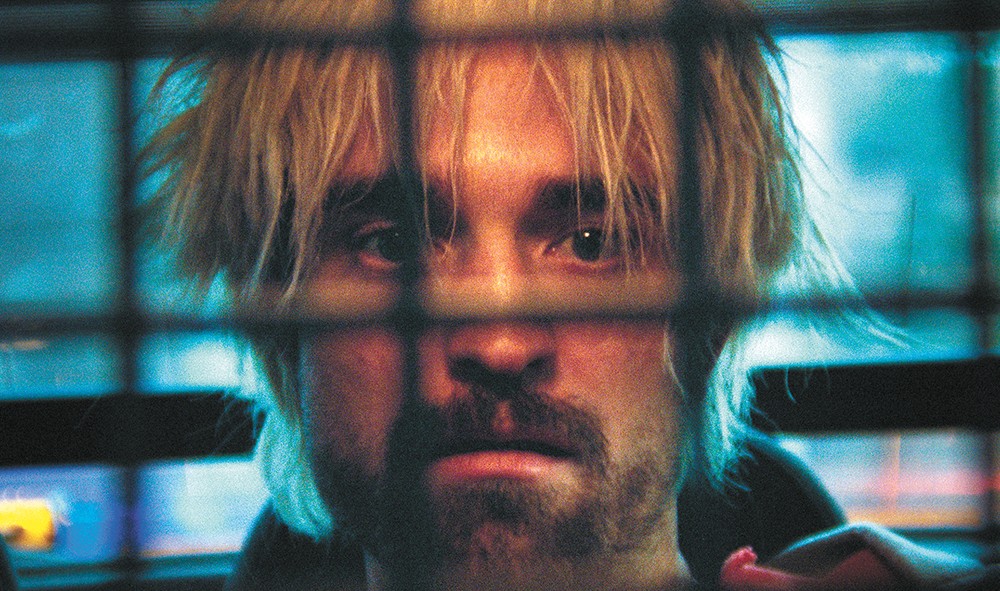

There is one quiet scene in Good Time, and it's the first, as Nick Nikas (co-director Benny Safdie) is asked to play word association with a social services psychiatrist. Nick is developmentally disabled; the psychiatrist is (likely) court-appointed. The camera cuts back and forth in tight shots between the two of them, with the shrink gently pressing Nick more and more to explain his answers, and Nick becoming emotional — a single tear rolls down his cheek — as he is unable to explain himself. Moments later, Nick's degenerate brother Connie (Robert Pattinson) bursts in. He chastises the shrink for making Nick cry, then herds Nick out of the office and into a life of crime, and Good Time puts its foot on the gas and never lets up.

This is a movie about decisions, and two main characters who make only bad ones. The first bad decision Connie makes — after taking Nick from the people who could help him — is to rob a bank with Nick's help. We see them standing in a teller's line, wearing masks designed to make them look like black men. They also have bright orange vests on, making it appear as if they're working construction nearby.

The bank robbery goes off well enough, until Connie makes another bad decision — though probably the best one under the circumstances — to have the teller go to the vault to gather more money. Although Connie and Nick ditch their robbery attire and masks and even have a livery driver waiting to take them to Port Authority in Manhattan, they don't count on the anti-theft pack hidden with the cash. It explodes and covers them in fluorescent puce-colored powder, rendering most of the money useless.

Connie hauls Nick to a fast-food restaurant to get cleaned up — at first, Nick uses toilet water to get the powder off of him — and stuffs the bag into the bathroom ceiling. Then, back on the street, nearly clean but clearly covered in anti-theft powder, Nick and Connie are chased on foot by cops until Nick crashes headfirst through a glass door and is arrested.

I've described only Good Time's first 15 minutes; the rest of the movie is so bonkers, so completely unpredictable, that it's completely exhilarating. There's little character development, but plenty of plot to keep it hurtling forward, as Connie tries in vain repeatedly to bail Nick out of jail, yet it never feels episodic or disjointed or inorganic. It exists as a piece of pure cinema; all it asks is that you accept it and go along.

If you grimace at four-letter words, fistfights and the occasional screaming match, Good Time isn't for you. But if you're willing to let Good Time roll, it's something to behold. Whether Connie is scamming his oblivious girlfriend Corey (Jennifer Jason Leigh), pleading with a bail bondsman, or dealing with characters who make even worse decisions than he does — and there are several — there's no letting up.

The script, by Ronald Bronstein and co-director Josh Safdie, has Connie tumble from one bad situation to the next, and Sean Price Williams' cinematography is a wonderfully skittery jumble of handheld shots, extreme close-ups and static work that changes with Connie's mood and circumstances. Daniel Lopatin's emphatic electronic score ramps up tension or eases it at just the right moments, and there isn't a false note from the actors.

Pattinson's performance is worlds away from Edward the vampire in the Twilight franchise, but he's been turning in dynamite, under-the-radar work for years (see Maps to the Stars and The Rover). Buddy Duress, who's so good it's almost like he's not acting, pops up halfway through the movie as the guy who makes worse decisions than Connie, and Benny Safdie is heartbreaking as Nick.

There hasn't been such a thrill ride in what feels like a decade. Good Time is one of the best films of the year. ♦