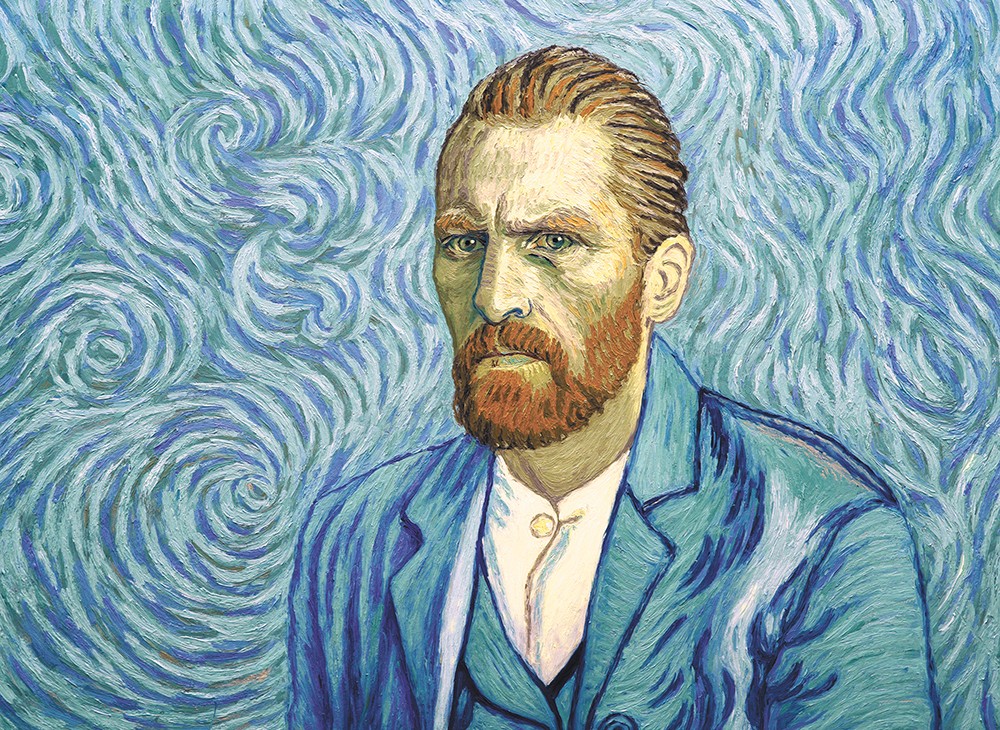

You've no doubt heard a film's visual style being described as painterly, but Loving Vincent takes that idea to new levels.

The movie is being advertised as the first hand-painted feature, a feat accomplished by a team of approximately 115 artists painting over each individual frame of live-action footage, shot mostly on green screens. Similar rotoscoping techniques have been used before by filmmakers like Richard Linklater (Waking Life, A Scanner Darkly) and Ralph Bakshi (American Pop), but never this evocatively. A portrait of the final years of Vincent van Gogh's life, it practically pulls us headfirst into the world of his iconic paintings.

By all accounts, van Gogh was a man of contradictions and wildly shifting temperaments, no doubt the symptoms of a mental illness that has been posthumously diagnosed many times over. Unknown during his lifetime, he is now considered one of the godfathers of post-impressionism, a movement that is itself somewhat contradictory, usually depicting natural settings through a lens of colorful abstraction.

Loving Vincent is set in the late 1890s, about a year after van Gogh's agonizing suicide by gunshot and long before anyone had anointed him a master. Douglas Booth plays Armand Roulin, the son of a bushy-bearded postmaster (himself the subject of an actual van Gogh portrait) who's sent to deliver a long-lost letter Vincent had written to his brother Theo.

Armand travels to Auvers-sur-Oise, the sleepy village outside Paris where van Gogh died, unaware that Theo has also passed away. He hangs around to talk to those who knew Vincent — the proprietor of the inn, the doctor who treated him, the young woman who may have pined for him — and finds himself becoming obsessed with piecing together the events of the artist's final days.

The real people and places van Gogh painted during his short but prolific career weave their way in and out of the plot, and anyone with a passing familiarity with his oeuvre will no doubt recognize some of the characters and the scenery — the café terraces, the wheat fields, the gardens and, yes, the starry nights.

Loving Vincent essentially borrows the same framework as Citizen Kane: It's all about uncovering the secrets of a dead man's life, told via flashback by his acquaintances who came to love, fear and pity him. But it also owes a debt to Akira Kurosawa's great Rashomon, as each new piece of information brings with it another mystery. Why exactly were Vincent and Theo estranged? Did Vincent really intend to kill himself, and if so, why? And is the quirky local doctor to be believed when he suggests Vincent was shot by someone else?

Even though it's borrowing from a couple of watershed movies (and it's probably unfair to even mention them in relation to this film), the narrative here grows a bit repetitive, and even at 90 minutes, it wears itself thin before it's over. For a film about such an unconventional, impressionistic mind, it's not too adventurous in its dramatic structure.

Still, the film presents the unusual opportunity to treat the movie theater as an art gallery. Even if Loving Vincent doesn't quite connect on the emotional level it intends, it's a marvel to look at, and a remarkable showcase for years of painstaking work. You can see each individual brush stroke up there on the screen, and even the backgrounds seem to bristle with activity, giving us the same sensations that particularly tactile stop-motion animation does.

The story may not be as engaging as the visuals, but the film is worth seeing simply to gaze in awe at its images, to let it wash over you in warm, sun-dappled waves. ♦