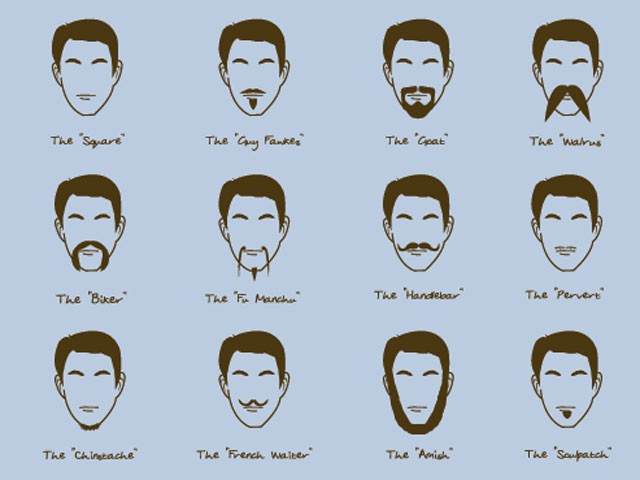

Men grow goatees, mustaches, sideburns, soul patches, chinstraps, handlebars and five o’clock shadows. At times, men resemble grizzlies, walruses and even goats.

When a man grows facial hair, he can look distinguished — or disheveled, depending.

A casual glance around will reveal that men are in a renaissance of hirsute glory. Every type of facial hair can and will be seen. It’s a popular theory that most men are clean-shaven, but it could very well be wrong: the bearded ones, especially at this time of year, almost outnumber the hairless.

But why? It’s estimated that a 15-year-old boy will cut 30 feet of hair off his face, and spend almost 3,000 hours doing such, by the age of 80. We blow $1.1 billion a year on razors and blades.

Last month, a handful of the guys here at The Inlander (and thousands more around the world), participated in “Novembeard, A Celebration of Manhood.” By month’s end, we had ourselves a veritable forest of whiskers furry-ing our faces. On Nov. 31, we lined up chin by chin for viewing and voting. The best beard (hard to define, so we let our judges select their own criteria) won a plastic bottle of cheap vodka — and, of course, undying admiration.

The history of the beard, however, stretches far into the past.

Facial hair, naturally, preceded tool making, especially the sophisticated designs of King Camp Gillette and Max Braun. Evidence suggests that men began some form of shaving 100,000 years ago, though calling it shaving is too kind. It was more of a plucking. With clam shells.

The first razors date back 30,000 years — little fl int blades that scraped the scruff from Stone Age jawlines.

Since the beginning of recorded history, though, the beard has had as many meanings as there are hairs on a man’s face.

In Europe, beards were regarded as divine before the coming of Christianity, which viewed beards as libidinous and diabolical. Ancient Egyptians also viewed facial hair as godly and went as far as crafting goatees from gold to strap upon their leaders’ — male or female — chins.

The Greeks were hairy until Alexander the Great, who ordered his troops to shave so that their chin hairs couldn’t be used against them in hand-to-hand combat. This proclamation had the effect of switching the grooming habits of slaves (shorn to identify servitude) and those they served. After Alex, slaves grew beards.

Peter the Great of Russia, pro-Western and anti-beard, made hairy noblemen pay a beard tax, as well as wear a medallion describing their facial hair as a “ridiculous ornament.” (One anecdote from the early 18 th century suggests this discrimination came after a visiting European noblewoman embarrassingly pointed out the leavings of a sneeze dangling from Peter’s soon-to-be-sheared face.)

During the First World War, with its trench battles and mustard gas, men realized that a clean face allowed for a better seal with a gas mask. Here, being hairless was a matter of life and death.

This war was, many say, the beginning of the end for the British Empire, whose leaders at one point commanded the world — as well as some extremely long lochs of facial hair. Piers Brendon, in the British Daily Mail, traces facial hair to the empire’s fortunes.

“The rise and fall of the Empire was reflected in the waxing — literally, sometimes — and waning of the hair on generations of stiff upper lips,” Brendon wrote. By the time of the Suez Canal, the recognized and embarrassing end to the empire, English moustaches were anything but impressive.

Here in the States, we’ve had our own history with commanding facial hair.

Abraham Lincoln grew a beard, sans ’stache. He is our most famous of furry commander-in-chiefs, and many say he started the presidential trend of being bushy. In the subsequent 60 years, candidates for that high office sported all kinds of growth, especially in the three elections following Lincoln’s presidency, in which a bearded candidate walloped a clean-shaven opponent. The last man with facial hair to sit in the Oval Office was William Howard Taft, who left office in 1916. Between him and Lincoln, only Andrew Johnson and William McKinley had baby faces.

In the years following, the occasional mustache appeared on the campaign trail (Republican Thomas E. Dewey in ’44 and ’48; Libertarian Bob Barr last year) but political heavies generally opted to go razor-less only in times of political wilderness (Al Gore after 2000).

We can only hope that Barack Obama will add another layer of history-making to his already historic presidency by growing a goatee.

Men will have their beards. Gilgamesh and his later incarnate, Noah, are said to have had huge beards. Confucius had whiskers. Ernest Hemingway, John Lennon and, by most accounts, even God (the Father version) — rejected razors. So only men can know what it is to partake in the cultivation of facial hair.

Over the last decade, I’ve had an evolving (and, by some accounts, devolving) relationship with pogontrophy (“the cultivation of beards; beardedness”). Pictures of me show beards, moustaches, beards with shaved chins, muttonchops and, for Novembeard, a very hairy and offensive neck beard that fi nally connected all of my body’s hair (to the chagrin of both girlfriend and boss).

My menagerie of stylings has always been generally accepted.

According to Allan Peterkin, the author of One Thousand Beards: A Cultural History of Facial Hair, we are living in the “greatest boom in facial hair since Victorian times.” George Clooney occasionally sports a beard. Brad Pitt has a goatee. The ironic mustache graces the upper lips of too many hipsters, and the thin, excessively well-groomed chinstrap beard lines the jaws of too many homeys. Even Chuck Norris and his ginger beard are cool again.

What’s a guy to do? Easy. Don’t shave. Free the beard.

The author of this article won last month’s Novembeard contest at The Inlander. He quickly reduced his hirsuteness to a goatee.