The phone call came as she was out walking dogs on a Boston sidewalk. The doctor was on the other end. He told Cecilia Izzo that he hadn’t wanted to worry her over the weekend, so he hadn’t told her his concerns. But the test results looked bad: lung cancer.

“I remember the day,” Izzo says. “It’s kind of like 9/11.”

She says she wandered around in a fog for months. Izzo moved to Seattle, believing that, if she were to die, she would want to do it in a place she loved. She only cried twice — she didn’t want to frighten her young children. After all, although 15 percent of those with breast cancer die, only 15 percent of those with lung cancer survive. By far, more people die of lung cancer than any other cancer.

The dangerous part of lung cancer is its stealth — you can’t check for it easily. Without nerve endings inside the lungs, the cancer can spread, and the tumor can grow, undetected. By the time it is clear that something’s really wrong, it can be too late.

If a CT scan hadn’t caught the subtle abnormalities in Izzo’s lungs, she wouldn’t be alive today. That’s why a new study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, is so important. It looked at 53,000 people and examined how effective CT scans were at detecting cancer in that high-risk population.

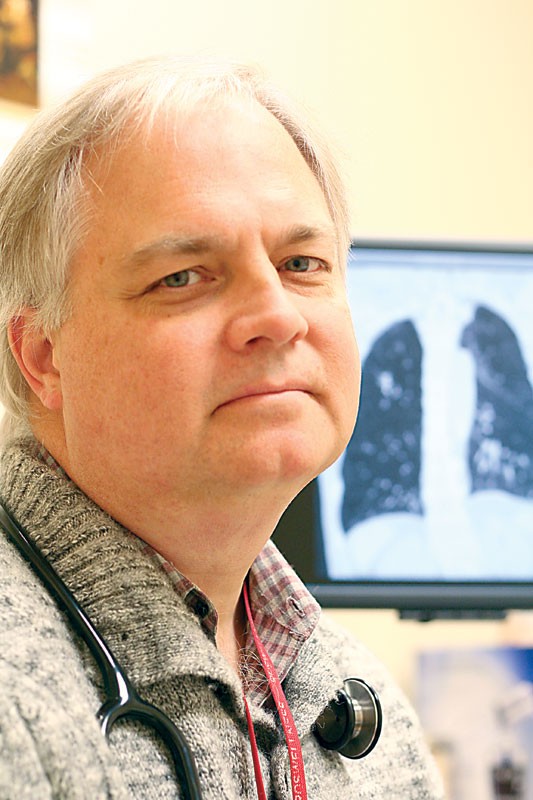

“The article that was published last summer was really a landmark study. There’s never been one done like it before to look at lung cancer screening. The study was remarkably positive,” says Greg Loewen, director of the Providence Cancer Center’s lung cancer program. “If you’re a smoker and you smoked for 30 years, and you’re 54 years old or more, if you get a CT scan, your chance of dying from lung cancer drops 20 percent.”

Izzo had been a teen smoker, and though she quit, she’d waited tables for years. She’d soaked up plenty of smoke, both firsthand and secondhand.

Douglas Wood, endowed chair of lung cancer research at the University of Washington, says studies indicated that CT scans could be valuable a decade ago. It took this large, expensive, lengthy randomized study to show just how useful.

But screening methods, if not sound, can actually be dangerous.

“The most common harm is the identification of false positive findings — that is, an abnormality that requires additional testing, particularly invasive testing, like a biopsy,” Wood says.

Prescribing lots of tests for patients has often been pointed to as a culprit for driving up the costs of health care. But by identifying patients particularly prone to lung cancer — smokers — the health care system can actually save money.

“If you take, let’s say, a patient with Stage 4 lung cancer, metastatic lung cancer, the average survival is six months,” Loewen says. They may spend $100,000 on chemotherapy to get a month or two more of life. On the other hand, a CT scan, which may catch cancer far earlier — when it’s more treatable — costs $250.

Such scans aren’t perfect — there’s still a significant number of false positive results. At Providence, Loewen says, they’re continuing to try to improve detection.

“We’re looking at a parallel way of lung cancer screening,” Loewen says, discussing another national study examining the effi cacy of a procedure called autofluorescence bronchoscopy, similar to colon cancer screening.

Meanwhile, the CT scans show promise in another way as well. Wood says that not only did lung cancer deaths decrease by 20 percent, other causes of death fell 7 percent.

“It means that the screening studies may be sifting out other illnesses or cancers,” Wood says.

Lung cancer, however, remains the top cancer killer, beating out the next four types of cancer combined. Yet, outside of anti-smoking ads, lung cancer research has nowhere near the public presence of breast cancer.

“I think that breasts are prettier than your lungs. I think its sexuality,” Izzo says. “Also, since they have so many survivors, then they can conduct their forces.”

Today, living in Seattle, she coughs occasionally on the phone. Surgeons removed one lung and a chunk of the other in the effort to save her life. She can’t go backpacking any more — though she’s been able to walk, slowly, a few half-marathons.

More than seven years after her diagnosis with Stage 4 lung cancer, Izzo says, “My joy is still being alive and seeing my girls in college.”