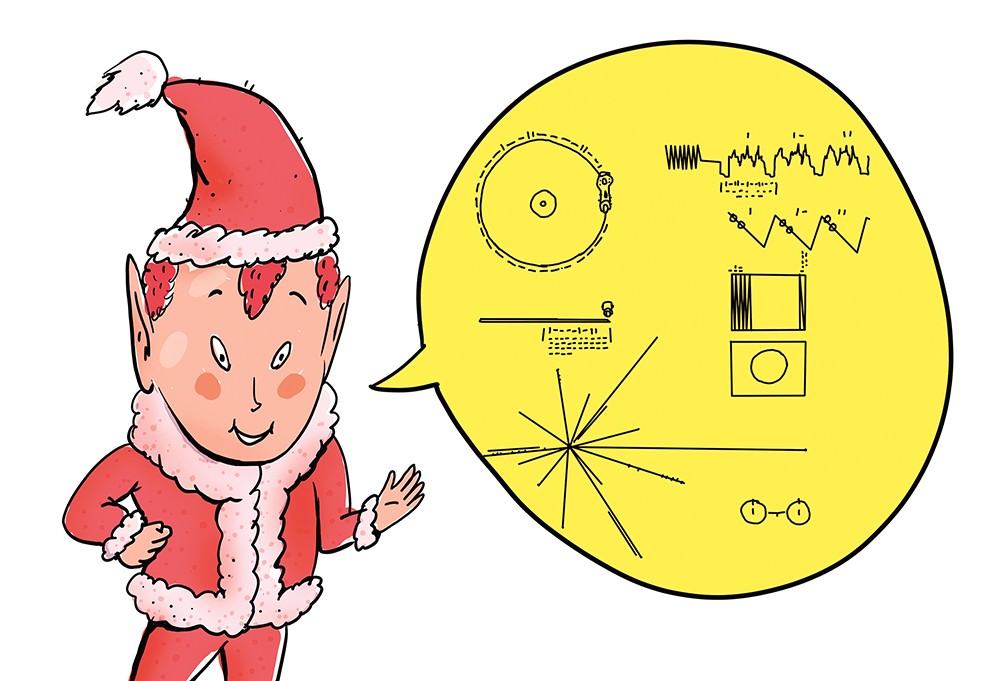

In the summer of 1977 NASA prepared to launch the Voyager Mission, two interstellar probes on a quest to travel beyond our solar system. The mission was a pursuit of scientific discovery, but it also acted as an intergalactic greeting card. Each spacecraft contained a single Golden Record, a copper phonograph plated in gold, that could be played by extraterrestrials on a parallel mission, should such beings exist and had the wherewithal to be equipped with a record player.

The Golden Records carried salutations in over 50 languages (including whale song), classical and traditional folk music, and the EEG of a woman in love. That woman was Ann Druyan, the creative director for the Golden Record project, who days before recording her brainwaves for posterity, got engaged to Carl Sagan, the popular astrophysicist who happened to also be the chairman of the Golden Record commission.

Druyan, by her own admission, said finding love with Sagan was a eureka! moment, an astounding discovery that a perfect match was indeed a possibility in the universe. For science, the Golden Record commission wanted to preserve that discovery and ship it out to aliens as representative of the human experience. The fact that aliens might not exist, to some degree, was beside the point.

I find the Golden Records a sweet reminder that humans often reveal themselves when trying to communicate with the unknown. The fact that aliens might not exist didn't stop Sagan or Druyan from collecting samples of humanity — art, music, a simple hello — or from being deliberate when considering the impression humans would make in First Contact. I admire a project that many would consider frivolous, but is executed with an abundance of care by those responsible for the mission.

During the holiday seasons I often think about a different kind of message. For most of my childhood my grandfather wrote letters to my siblings and me in the days preceding Christmas. Written in a nearly illegible script, the letters were dispatches from the North Pole penned under the guise of "The Red Elf," a character my grandfather invented one day in response to my challenging questions: How does Santa have time to deliver presents to all of the kids around the world? Who organizes the toy factory at the North Pole? Who helps Santa answer all of the Christmas letters?

Some kids accept the story of Santa without a second thought. I was not one of those kids. The Red Elf, my grandfather explained, was Santa's right-hand-man, an essential part of the Christmas Industrial Machine. My grandfather graciously stepped in to take a frivolous inquiry very seriously.

My line of questioning, though, is not so different from what many of us do throughout our lives: Ask the adults around us a series of pestering questions to explain the confusing bits in the world. The letters my grandfather sent to us certainly extended the lifespan of the Santa story — they described a world of reindeer and workshops, snow drifts and elf labor unions. Ultimately, though, they described my grandfather, someone who wanted to create an elaborate fantastical world for his grandkids to inhabit.

It's been nearly 20 years since my grandfather passed away, nearly 30 since he wrote his last Red Elf Letter, but the spirit of his message lives on when I think about the traditions I intend to create with the people in my life. My hope for the end of the year is that all of us take the time to consider the messages we're leaving behind, the dispatches that travel beyond our individual worlds for an infinite time in space. ♦

Aileen Keown Vaux is an essayist and poet whose chapbook Consolation Prize was published by Scablands Books in 2018