The town of Cheesebridge — the setting for The Boxtrolls — rises from the water's edge like a traffic cone dotted with teetering Victorian buildings. It's a mad, dizzying construction of spiraling streets and a complete absence of right angles, one that — in theory — could have been created on a computer for any animated feature film. But it wasn't. It exists in three dimensions in the real world. And don't think for a moment that isn't part of what makes The Boxtrolls so thoroughly delightful.

"Animated film" in the 21st century has come to be so specifically defined as one thing — CGI animation — it's sometimes hard to remember that there are many other ways to create fantastical worlds on screen. LAIKA's stop-motion universes in previous releases like Coraline and ParaNorman were engaging in their uniquely tactile quality, but there's been a next-level leap to the work on display in The Boxtrolls. This is world-building in the most literal sense of the term.

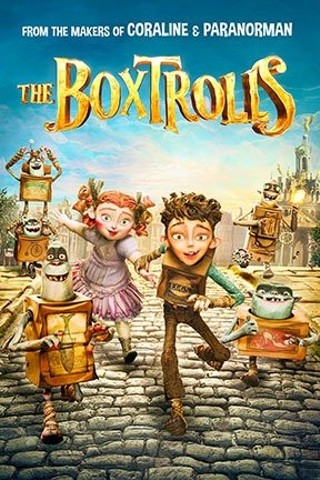

This is not to slight the narrative in any way. Loosely adapted from Alan Snow's 2005 book Here Be Monsters!, it tells the tale of the titular creatures, reclusive scavengers who live beneath the surface world in the heart of Cheesebridge's pointy mountain. Yet they're believed to steal babies and eat humans — a story given some credence by the disappearance of one infant 10 years earlier. The "Boxtroll exterminator" Archibald Snatcher (Ben Kingsley) is trying to maximize that fear in order to move up the Cheesebridge hierarchy into the world of the "white hats," even as the now 10-year-old Boxtroll-raised human boy, called Eggs (Isaac Hempstead Wright), begins to wonder if he may belong to a different world.

The screenplay adaptation by Irena Brignull and Adam Pava does a fine job of establishing the stratified society literally represented by Cheesebridge's conical structure. The town's self-absorbed, cheese-nibbling, white-hat-wearing oligarchy — led by Lord Portley-Rind (Jared Harris), whose neglected daughter Winnie (Elle Fanning) winds up befriending Eggs — provides the perfect launching pad for Snatcher's disgruntled sense of entitlement. While The Boxtrolls never pushes the point very hard, there's an effective undercurrent of the scapegoating that emerges in a culture where there seems to be no way to move up, leaving the inevitability of crap rolling down a very tall hill.

Yet the greatest pleasures in The Boxtrolls come in the way this world is realized physically. The characters are remarkable creations: the whimsically grotesque Boxtrolls themselves in their name-identifying package clothing, including Eggs' surrogate father, Fish; the snaggle-toothed, pot-bellied Dickensian villainy of Snatcher; and the trio of henchmen who assist Snatcher, occasionally questioning whether they're the good guys. The animators imbue these weird little creatures with genuine performances and personality, more than ably assisted by great vocal work — particularly from Kingsley, who prowls deliciously around every one of Snatcher's elongated utterances.

It's even more remarkable absorbing the detail in the sets, from the aboveground world of Cheesebridge to the cavern where the Boxtrolls light the "sky" with purloined bulbs, and craft massive machines with rescued gears, springs and scrap metal. Directors Graham Annable and Anthony Stacchi move their characters around those sets with a precision that indicates the value of every micro-millimeter motion. Filmmakers choreographing live-action set pieces would do well to take a few lessons from The Boxtrolls on how to take advantage of the space in which action is occurring, and the value of knowing the arc of a sequence before you start trying to find it in the editing room.

There's a demented side to The Boxtrolls that's bound to be a little off-putting for some viewers, whether it's the Boxtrolls' gleeful eating of bugs or the unfortunate fate of some of the characters. At times, it feels like an Edward Gorey version of one of those vintage Rankin-Bass stop-motion Christmas specials, with a few wickedly witty verbal asides, like the incongruous chant of one of Snatcher's henchmen when a mob gets worked up. But there's just so much imagination in every frame that it's hard not to feel the joy of its creation. Maybe something special happens to a movie's world when someone has held it in the palm of his hand. ♦