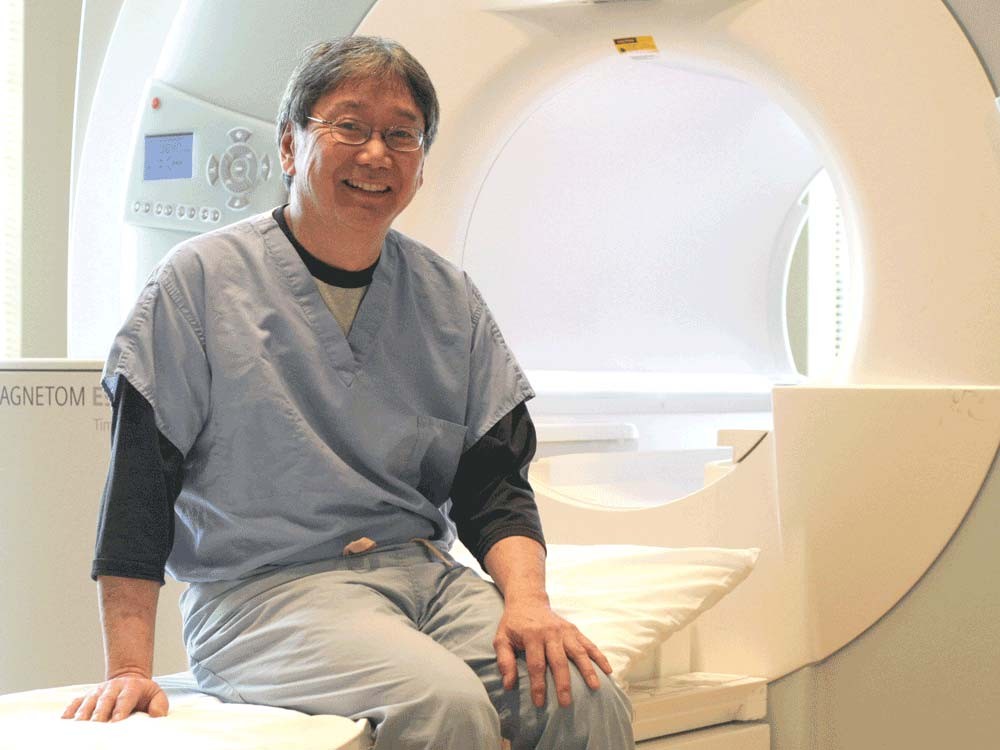

Dr. Arthur Watanabe leans back in a chair in his waiting room as he talks about a patient in his mid-20s who is so ridden with pain that he can’t use his left arm.

“Spinal-cord stimulators are his best chance for longterm improvement and relief, so he can get off narcotics and lead a meaningful, productive life,” Watanabe says.

Some patients have found spinal-cord stimulators (implanted devices that deliver slight electrical shocks) are able to mask their pain with tingling. It’s expensive and doesn’t work for everybody, but, Watanabe says, it can dramatically improve quality of life for some.

As of 2010, however, this patient’s Labor and Industries insurance stopped covering spinal-cord stimulators. And many of Watanabe’s other procedures, for that matter.

“From 2009 to now, my patient volume is down by 50 percent,” Watanabe says. “I used to do 25 [spinal-cord] injections a day. Now I do eight or 10 a day.”

The economy is partially to blame, of course. But Watanabe has another target, too: the Washington State Health Technology Assessment (HTA) committee. The committee assesses the effectiveness, risks and costs of medical procedures and devices covered by Washington for state employees, Medicaid patients and injured workers.

The committee has garnered scrutiny recently — even making headlines in the New York Times — because it explicitly weighs the costs in determining what state insurance will cover. Critics of national health care reform have held the program up as proof that federal reform could lead to rationed medicine and reduce options for patients.

For Watanabe, an interventional pain management specialist, that’s been true. “They’re eliminating my practice,” Watanabe says of the committee. “They’re reducing access for a lot of patients.”

In 2006, Watanabe opened Spinal Diagnostics, a small medical office in Spokane’s University District. That same year, the HTA committee was formed to analyze potentially wasteful or controversial procedures.

In the beginning, Washington’s insurance process had largely avoided controversy as it received praise for being transparent and innovative in assessing “evidence-based” medicine. But then a national spotlight was trained on the committee.

“Merely the spectacle of doctors [being] forced to justify their practices, if not yet their existence, to a government board is troubling enough,” the Wall Street Journal editorial board wrote last month. “We’re told that no one should worry because this future will be based on ‘evidence,’ but as Washington state shows, evidence and rationality will have to compete with the overriding political imperative to control costs.”

So far, HTA committee Program Director Leah Hole- Curry says, no decision has been made on cost alone. Efficacy and safety come first. But she also brags that the HTA has saved the state $31 million.

Watanabe, meanwhile, feels his sub-specialty has been unfairly targeted by the committee. Three times, he has unsuccessfully applied to be on the committee.

“There’s no intentional effort to bring those types of technologies forward,” former HTA committee chair Brian Budenholzer says. “But those technologies carry many concerns about safety. In many cases, you’re invading the space where your spinal cord is.”

In 2008, the committee ruled against covering discography, a technique that uses needles and MRIs to diagnose back pain. They eliminated spinal-cord simulators in 2010. This year, the committee recommended denying coverage for a large swath of spinal injections, some of which Watanabe uses to treat back pain.

Budenholzer adds that most studies about the stimulators had very low sample sizes and never used a placebo group. And no evidence exists, a committee report reads, on their “long-term efficacy or safety.”

Watanabe, however, is critical of the way the HTA committee makes its decisions.

“[The HTA committee] gives physicians just a few minutes to make a presentation,” Watanabe says. He believes that the committee assumes physicians are biased. “Just because a randomly controlled trial says one thing doesn’t make it true.”

His procedures, he says, are about finding what works for each patient. And each patient is different.

“The

catch phrase is they want to ‘improve care,’” Watanabe says. “But if

you drill down and look at the real agenda, they’re trying to contain

costs.”

Watanabe accuses University of Washington research professor Gary Franklin of trying to eliminate the interventional pain management specialty. But Franklin strongly supports the HTA committee, arguing medicine should be either based on randomized controlled studies or well-designed observational research.

It’s the only way, he says, to stop runaway health care costs. “We have to look at what we’re paying for,” Franklin says. “A lot of what we’re paying for is unproven.” Medical devices are often regulated under obsolete standards, he says, and surgeries aren’t regulated at all.

“Do you pay millions of dollars for something that doesn’t work, but not cover 10,000 people?” Franklin says. “You can always find someone who thinks something works ... [but Washington state] law says to look at the evidence.”

Watanabe, however, worries that with national health care reform, he’ll soon need to contact Washington, D.C., for recommendations in treating patients.

“Taking care of a patient is still more of an art,” Watanabe says.

“It’s not something you can cookbook like the government and insurance companies [believe].”

For proof, he points to the patients he’s helped — those who can bike again, run again, garden again. He asks each patient to write a pain diary, testifying to their improvement.

“One pain diary I got back said, ‘Thank you for giving me back my life,’” Watanabe