When Quentin Tarantino is good, he’s downright genius. When he’s good, he makes me say ridiculous things like: Is it possible that this nerdy white boy has made the most important, most un-missable film yet about slavery in America? Could only a nerdy white boy get away with making a movie that combines the fractious urgency of Pulp Fiction and the visceral gore of splatter movies and the unfettered ranginess of westerns and make it about a black man killing white people and riddle it with countless repetitions of the “N-word”... and after all of that leave us with a sense that this is in no way a racist film, and is in fact quite the opposite?

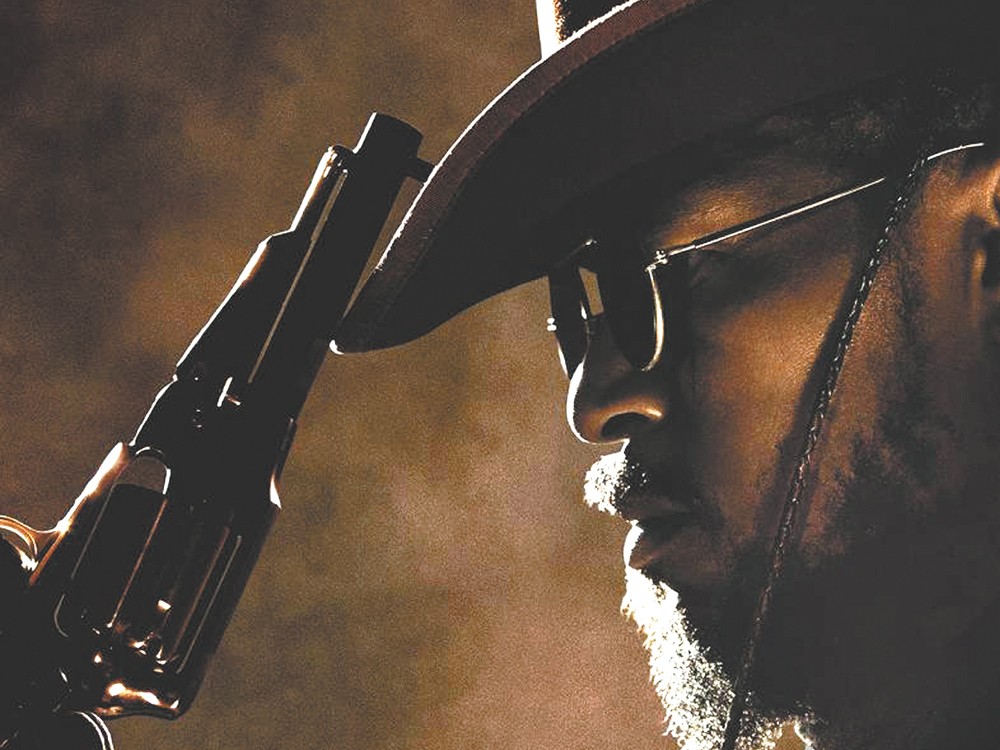

So many marvelous contradictions and astonishments to be found in Django Unchained. How is it that writer-director Tarantino can tell a story that could not be more about race and make it feel post-racial? Django is one of the juiciest, most complex, most intriguing, most human heroes pulp fiction has ever seen. As an unexpectedly freed slave in Texas in 1858, there couldn’t be a less color-blind role, but Tarantino treats the mere fact of his protagonist with a kind of offhandedness that might mislead you into suspecting there’s nothing particularly unusual about the story he has crafted around Django — and then he hands this role over to Jamie Foxx, who sashays into it with the same casual acceptance. It’s almost as if this is the product of some glorious future world in which black action heroes are as unremarkable in their numbers as white ones.

Tarantino spins a dark fantasia of the pre-Civil War South that is hilarious, ferocious, shocking and wise, sometimes all at once. This is Tarantino unchained, even more so than usual. He is unafraid to be pointed, as with the bounty hunter who frees Django: he is former dentist Dr. King Schultz, emphasis on the “Dr. King.” He is unafraid to be absurd, crafting for Django a wife still bound in slavery called Broomhilda (Kerry Washington), dubbed so by a German mistress... which creates in Schultz, also a German abroad, a sense of mythic obligation for him to help Django rescue her, what with Brunhilde, her namesake, being a German national heroine and all. And brilliantly, Tarantino dares to cast the indispensable Christoph Waltz as Schultz, in a very different role from the Nazi he played in Inglourious Basterds. Waltz is as deadpan funny here as he was chilling there, and in any other film that wasn’t so crammed full of awesome as this one is, you’d have to concede that he steals it. Here, what is one of the best performances of the year is just one more bauble to be dazzled by.

Tarantino plays with the power of myth on all sorts of levels, both overt and meta. It’s in the unexpected relationship between a brutal plantation owner (Leonardo DiCaprio) — to whose enterprise Django and Schultz trace Broomhilda — and his slave butler (Samuel L. Jackson), which undercuts literal and figurative black-and-white notions about slavery by exploring the complicity of some slaves in enforcing the servitude of others. It’s in the unexpected use of unlikely anachronistic pop music on the soundtrack, bringing together 20th- and 21st-century myths of open spaces and black power in a way that seems to slam open rooms in the American story that had been exclusionary of anyone not white.

Many filmmakers appreciate the mythic power of cinema, but few can so effortlessly whip up moments that create their own instant mythology, as Tarantino does with almost everything that Django does onscreen, while never being self-conscious about it. I don’t just love this film — I love that a film like this can exist and be this delicious and this smart and this daring and this kickass and take no shit from anyone.