In a Southern drawl, homeowner Richard Tennant reels off the long list of medical travails that put him on disability. “It’s pretty complex,” Tennant says. “Thirteen stents, had a heart attack, had open heart surgery, 10 knee surgeries, two botched back surgeries, prostate cancer, and breast cancer.”

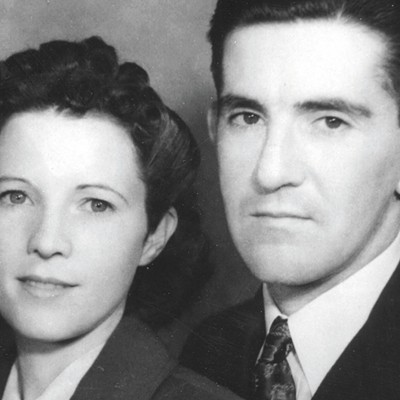

Blame genetics, blame his parents, blame the string of car accidents he had during the ’70s. But whatever the causes for Tennant’s many medical woes, the fact remains: He can’t work. And despite her experience raising six kids, his wife hasn’t found a job either. “Housewives are just not considered viable employees,” Tennant says. So instead, they scrape by on his disability check, carefully choosing what to go without and which bills to pay.

They still have their split-level house on Northwest Boulevard, left over from his wife’s divorce. But during winter, their power bill soars. A $168 power bill can be devastating on a tiny budget. “What are we going to do?” Tennant recalls thinking. “Pay the electrical bill? Pay for food?”

In some winters, they’ve put on long underwear and sweaters, shut off the heat in every room but the living room, and dialed down the thermostat. Yet the temperature in the house, he says, can only go so low before his “heart goes wacko.” Instead, for the past two or three years, Tennant and his wife have relied on energy assistance funds dispersed by the local nonprofit SNAP. Several times a year, low-income residents like Tennant have an opportunity to apply for the funds, which are automatically credited to their Avista account. “It’s been a godsend,” Tennant says.

But the energy assistance program only serves about a third of the families who are eligible — and this winter, 3,400 families will no longer receive SNAP’s energy assistance funding.

The culprit is the sequester, that slew of intentionally unappealing budget cuts designed to punish Congress for failing to reach a better compromise. They’ve impacted both federal programs, like Head Start, and the array of nonprofits that receive federal funding.

The Inland Northwest is no exception. With the sheer number of nonprofits in the area and their complicated funding streams, it’s difficult to fully assess the damage, but many, from Idaho’s Meals on Wheels program to Spokane’s NATIVE project, have been impacted.

Volunteers of America saw a Health and Human Services grant cut by $20,000, directly impacting Alexandria’s House, a home for teenage mothers, and Flaherty House, transitional housing for young men. “You can’t cut staff, because you have to have 24-hour staff,” says Marilee Roloff, president of Volunteers of America of Eastern Washington & Northern Idaho. Instead, the organization has had to examine options like buying fewer groceries and turning down the heat. The sequester’s cuts would have been easier to budget for, she says, had it not come in the middle of the year.

Nadine Van Stone, director of Catholic Charities’ St. Margaret’s Shelter for homeless women and children, says that thanks to the sequester, the shelter is only receiving about 35 percent of the federal funding it did the year before. Starting July 1, the shelter had $50,000 less for the next six months. With shelters across the city seeing increased demand and growing wait lists, that lack of funding hurts.

Lutheran Community Services Northwest lost $10,000 for its crime and sexual-assault victim advocacy service programs.

“We had to make a tough choice,” says Erin Williams Hueter, director of advocacy and prevention. “What was most important? Preventing crime or being available for victims coming forward? We had to choose to be there to help.” Ultimately, they laid off a staff member, and cut back on the amount of the sexual-assault prevention education they provided.

Local agencies in charge of disbursing funds to nonprofits also were affected. Aging and Long Term Care of Eastern Washington, which covers five counties throughout the region, lost $150,000. That’s impacted a number of nonprofits, including the East Central Community Center’s adult day care program, Spokane Mental Health Elder Services, and the Greater Spokane County Meals on Wheels Program. Aging and Long Term Care dipped into its reserves in order to blunt most of the impact, but that’s a one-time fix. If the sequester hasn’t been overturned by next year, Inland Northwest nonprofits that deployed band-aid fixes will have even more cuts to make.

For the people served by area nonprofits, things look uncertain as ever.

“I’m just like, ‘What else can they cut?’” Tennant says. “They’re cutting people’s throats.”

This November, he plans on applying for SNAP’s energy assistance again. He’ll call them and apply online, hoping he gets in.

“I could complain all day long, but it’s not going to change the government’s opinion about what they’re doing to save money,” Tennant says. “You argue about it, and you complain about it, then you accept the fact that it’s happening. Then you’ve got to get a plan. As far as our plan, it’s up in the air.”

*The original version of this story misstated the number of stents Richard Tennant had received.