Just $50 stands between David Hill and his freedom. From the third floor of the Spokane County Jail, on the other side of a thick glass window marred with scratches, the 48-year-old shakes his head. He believes he's innocent, but knows that if he wants to get out, he will have to plead guilty.

His eyes droop with fatigue. This is the longest he's been locked up, five days and counting. He had worked as a janitor and a prep cook in restaurants around Spokane until a few years ago when, he says, he burst three discs in his back delivering washers and dryers. Now, Hill collects aluminum cans and discarded car batteries to pay for bus passes and food. He camps out wherever he can, usually in Airway Heights behind a movie theater or the Zip Trip on Garfield Road.

Hill's troubles can be traced back to May, when an Airway Heights police officer found him sleeping on a sidewalk and searched his duffel bag. It was full of aluminum cans and trash, including, it turns out, a dirty plastic baggie that tested positive for methamphetamine. He was booked on a felony drug possession charge and initially was released. But Hill struggled to keep up with all of his court appointments — "I didn't have enough for a bus pass, so I had to walk," he says — and he was arrested again on Aug. 23 for missing court.

Hill tugs at his bright-yellow jail scrubs, with folded court documents peeking out from his breast pocket. A judge set Hill's bail at $500. Using a bondsman, who usually charges 10 percent to post bail on someone's behalf, Hill would need $50.

Penniless, he instead sits in jail, presumed innocent in the eyes of the law, costing taxpayers about $120 per day.

"It seems ridiculous that they're spending the money to have me in here when $50 gets me out," Hill says.

Monetary bail, by its very nature, allows people with money to walk free while their cases slowly wind through the system, while people without money accused of the same crime are trapped behind bars.

In a country that incarcerates more people awaiting trial than any other in the world — about 500,000 people on any given day, according to the National Institute of Corrections — the consequences of lockup, even for a few days, are well established. People lose jobs and the ability to pay back their debts. They're kicked out of their homes. Parents lose custody of children. Their mental health deteriorates. Some die.

In an often-cited case out of New York, Kalief Browder was charged with stealing a backpack when he was 16 years old. He was held on $3,000 bail for three years on Rikers Island. Browder spent two of those years in solitary confinement and suffered beatings from corrections officers and other inmates. It would have cost him $300 to secure a bond to get released, but Browder's family couldn't afford that. Prosecutors eventually dropped the charges in May 2013 when they lost contact with the only witness, and Browder was let go. He committed suicide at his parents' home in the Bronx in June of this year. His family says Browder's mental health deteriorated while he sat in jail, and he never recovered.

Sandra Bland is another example. Authorities say Bland committed suicide in the Waller County, Texas, jail in June, three days after she was arrested and held on $5,000 bail. A Texas state trooper originally pulled her over for failing to signal a lane change. According to news reports, Bland attempted to contact a bail bondsman to secure her release. It's not clear why the bondsman didn't help her.

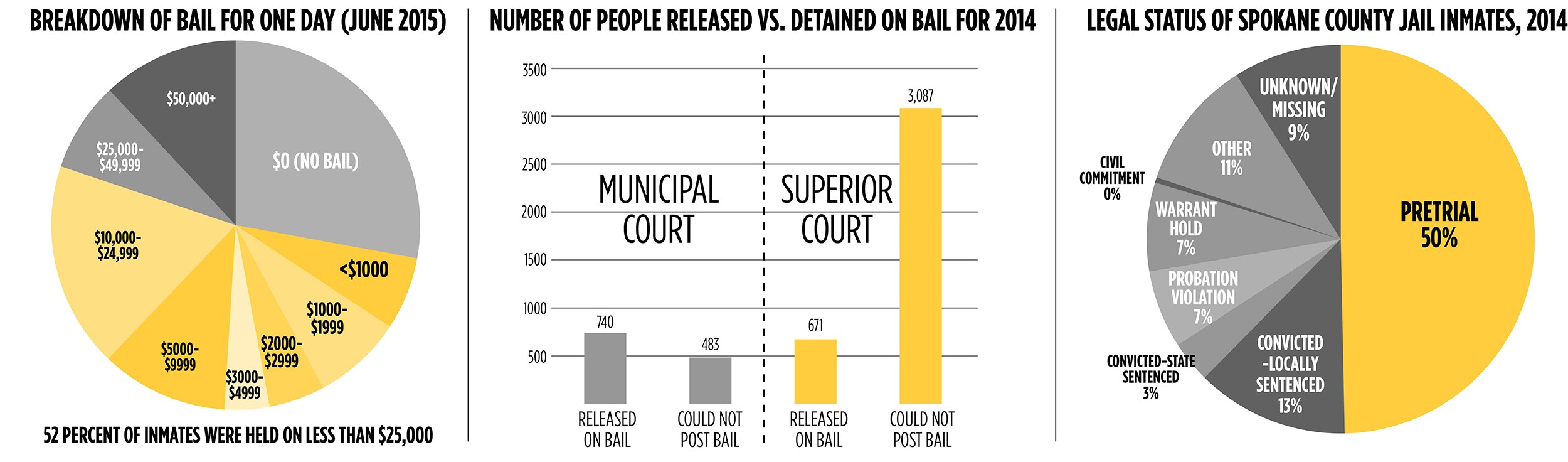

The Inland Northwest is no exception to the national trend. Half of the Spokane County Jail's population in 2014 was people awaiting trial, and a one-day snapshot in June of this year reveals that 440 out of 610 inmates — 72 percent — were held on bail. Similarly, a one-day snapshot of Kootenai County's jail population reveals that 74 percent were accused, but not convicted.

Since May, four people have died in the Spokane County Jail. The most recent, Tammy Heinen, was held on $2,500 bail. She was arrested on a parole violation while on her way to the hospital to have a leg infection treated. (A medical examiner later ruled she died from health complications.)

John Everitt spent four days in the jail after he was arrested on warrants in early May. He was held on $1,000 bail and hung himself with a bedsheet despite being on suicide watch.

Even short stays in jail can have dire consequences. According to a Bureau of Justice Statistics report from August, 40 percent of inmate deaths in local jails occurred within the first seven days of incarceration, and more than a third of all jail deaths in 2013 were suicides — the leading cause of jail deaths since 2000.

In the Spokane jail, the most common length of stay in 2014 was between one and seven days.

"Bail is the norm across the country," says Breean Beggs, a local attorney and leading advocate for criminal justice reform. "But for anyone who's concerned about equal protection under the law, government spending and public safety, they should want a different bail system. The current system is not equitable or effective."

The concept of putting up cash on the promise of returning to court to face allegations originated in medieval England. In 1689, the English Bill of Rights outlawed "excessive bail," meaning an amount so ridiculously high that it guaranteed detention. The same language was later adopted in the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which included three principles: Bail should not be excessive; all non-capital cases are bailable; and bail is meant to assure the appearance of the accused at trial.

In Washington state, a set of criminal rules guides judges' decisions whether to release people accused of crimes, though they're allowed wide discretion. The rules tell judges to consider violent criminal history and missed court dates, but also employment, enrollment in school, volunteer work, financial assistance from the government and housing. The idea is to prevent bail from keeping poor people locked up simply because they're poor. The rules also say that cash in exchange for release is a last-resort option, says now-retired Spokane County Superior Court Judge Jim Murphy, who had a hand in revising Washington's rules in 2002.

Nevertheless, says Murphy, "I think the inclination in this community is to set bond without careful considerations of factors in the rule."

Indeed, in 2014, when judges in Spokane decided on bail or release, they set bail 76 percent of the time. In 55 percent of those cases, defendants remained in jail.

Local judges say they'd consider releasing more defendants if there were more aggressive monitoring programs. Early efforts show promise. In 2013, the county's Office of Pretrial Services started monitoring people released on felony charges through daily check-ins. That year, out of the 502 people on monitored release, 76 percent made it to all their court dates, and 81 percent weren't charged with any new crimes. Since that expansion in 2013, Pretrial Services estimates it saved the jail $12.3 million.

Being released before trial can impact the ultimate outcome of a case. A recent study from the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that pretrial detainees pled guilty and were convicted more often than those who are released. Similarly, a 2012 report by the New York City Criminal Justice Agency, a nonprofit in charge of pretrial supervision in Queens and Manhattan, found that non-felony defendants held in jail before trial were convicted 92 percent of the time; of those released before trial, only 50 percent were convicted.

In other words, people behind bars are more willing to cut a deal, often when it may not be in their best interest. Their final sentences can vary greatly, depending on how long it takes their case to make its way through the system. In fact, a recent study showed that pretrial detainees receive sentences three times as long as those released before trial.

"The unfairness in the whole system is sometimes people plead guilty to a charge that they maybe would have fought," says Kathy Knox, a Spokane public defender. "But they didn't, because they didn't want to wait until trial. They wanted to get out right away. They have no leverage, they have nothing."

It's a quarter past 10 on a Monday morning, and a public defender passes out questionnaires to people arrested for minor crimes over the weekend. Some people booked into jail are immediately released if there's not enough room, but this group was held for one reason or another: Their crime was too severe; they missed too many court dates; their initial bail was too high. They answer questions about employment, income, school enrollment, medical issues and food stamps. The attorney stands in the front of the room like he's starting class. Some people raise their hands to ask questions.

From tiny Courtroom D in the Spokane County Courthouse Annex, a commissioner, who takes the place of a judge for first appearances on misdemeanor crimes in the city, reads the group their rights through a video camera. All in-custody first appearances are done through videoconference. The commissioner calls the first name, and a man with a red mohawk takes a seat beside the public defender. The prosecutor rattles off a police officer's summary of the incident, attempting to establish probable cause to charge the defendant. The public defender says "Not guilty."

Next, the commissioner will decide to release or set bail — possibly the most important decision in the entire case. The prosecutor launches into a familiar pitch.

"Your honor, the defendant has another assault charge from last year and missed a prior hearing for that. He's also failed to appear three other times this year. We recommend maintaining the bond set over the weekend to ensure his appearance in court."

The public defender rebuts: "Judge, my client asks to be released on his own recognizance. And he has something he'd like to say."

"Your honor, I realize I missed my last court date, but before that I went to the past four or five," the man says. "If I don't get out before the first of the month, I'm not going to be able to pay my rent, and I'll get kicked out. I been homeless for five years, and I just got off the streets. I'm begging the court. I promise I will not miss again. It was because I was moving that I missed my court date."

The commissioner furrows his brow as he studies the computer screen in front of him.

"Given your history of not showing up, I'm just not confident you're going to come back," he says. "So you do have a stable residence now, and what kind of income do you have?"

"SSD and SSI," says the man, indicating Social Security benefits.

"Alright, the concern I've got is this is the second warrant on this case and there's allegations of noncompliance with probation. That doesn't lend a lot of confidence in you getting to court next time around."

"I understand that, your honor, but I'm begging the court to give me one last opportunity to prove that I can do what I need to," he says.

"Well, I'll give you a better chance," the commissioner says. "I'll reduce bond to $1,000 and authorize GPS monitoring if you're able to come up with the money. You're looking at about $100 with a bondsman."

The man lowers his head into his hands. He can't afford that. "If I'm not out by the first, I won't be able to pay my rent, and I'll be back on the streets," he says.

The commissioner sets his court date for Sept. 11. At the time of publication, the man was still in jail.

The rest of the cases result in similar outcomes. Recently missed court dates, warrants or violent crime convictions almost guarantee a bail of some kind. As the prosecutor petitions the commissioner to maintain bail set over the weekend, he glances at each person's history — flagging the words "violent," "warrant" and "failure to appear," often even if the record shows that previous charges were later dismissed.

Defendants' last resort is a bail bondsman. For a premium, typically 10 percent of the total amount, a bondsman will put up the money. However, even this doesn't guarantee release. Bondsmen take into consideration the same factors as a judge, including income. People with no income and no way to pay the premium or secure the remainder return to their cells to wait.

Spokane County has dipped its toe into the bail reform waters. This month, the Spokane Regional Law and Justice Council, a group of law enforcement officers, judges, prosecutors, public defenders and elected officials, compiled data from every corner of the criminal justice universe as part of a competition to receive up to $2 million a year for two years from the MacArthur Foundation. The goal is to reduce the jail population and recidivism rates. Pretrial decision-making, including the use of monetary bail, is high on the list of anticipated reforms.

"It's about moving from an offense-based system to an offender-based system of decision making," says Jacquie van Wormer, the Law and Justice Council's administrator.

She's talking about a program that will provide law enforcement, attorneys and judges with an individualized picture of each defendant, and highlight factors contributing to their crimes, including homelessness, substance abuse or mental health issues.

"It's a huge decision whether to hold or release someone," says Spokane County Superior Court Judge Maryann Moreno, a proponent of pretrial reform. "And right now there are lots of things we don't know."

That information means nothing unless judges have options for supervised release. Sending a person who is in court for crimes of poverty back to the streets with a court date is like setting them up for failure, Moreno says.

"There's a whole plethora of conditions we could impose that we don't, because the infrastructure will not support it," she says.

More aggressive pretrial release supervision such as home visits and electronic home monitoring are among the ideas being thrown around. But they cost money.

Spokane County Sheriff Ozzie Knezovich isn't confident that the grant from the MacArthur Foundation will be sufficient to fund these initiatives long-term, nor does he think that releasing more people before trial will effectively decrease the jail population.

"The bottom line is it's time for the city of Spokane and Spokane County to put their money where their mouth is and fund programs [like pretrial services]," he says. "You're not going to have an extreme drop in jail population unless you actually build a Community Corrections Center."

He's referring to a new 24-hour receiving center to replace Geiger Corrections Center. The proposed facility would provide offenders with transitional housing, drug treatment and employment services. It's one recommendation that came out of the Blueprint for Reform, a report with suggestions to improve the criminal justice system in Spokane County.

Community Court is another effort already in place that could prove an effective way to reduce the jail population. The diversionary court is an option for less serious crimes like trespassing or disorderly conduct. It's held every Monday in the Spokane Public Library downtown and offers a more regular schedule for people struggling to make sporadic court dates. Service providers attend every week, making it a one-stop shop for people whose crimes stem from other issues.

Bail reform is hardly a novel idea. Eliminating monetary bail is one way to ease the system's grip on poor people, says Cherise Fanno Burdeen, executive director of the Pretrial Justice Institute, a nonprofit advocacy workgroup within the Department of Justice. She points to Washington, D.C., as a model example.

In D.C., monetary bail is illegal. No person accused of a crime can be detained because they're too poor. Instead, judges can hold people they believe are too dangerous through a preventive detention statute. That means about 85 percent of defendants are released on their own recognizance or to a monitoring program. Only 15 percent are held in preventive detention.

"Money cannot be used in a fair and equitable way," says Clifford Keenan, director of the Pretrial Services Agency for the District of Columbia. "It will not assure community safety or return to court, and ends up penalizing persons who don't have the resources."

Of those people released to pretrial supervision in 2013, 90 percent did not get re-arrested during the pretrial release period; 88 percent made all of their scheduled court appearances. According to the D.C. Department of Corrections, about half of detainees in D.C. are locked up pretrial, the average population has trended downward since 2010.

Then there's Multnomah County, Oregon, including Portland, where most low-level offenders are released pending trial. The rest see an officer with the Recognizance Unit to determine if they qualify for a jail bed. The Recognizance Unit acts as a 24-hour gatekeeper to the jail. If, based on the assessment, a person is determined to be too dangerous or too much of a flight risk to qualify for pretrial supervision, they're held until they can see a judge.

Oregon also has done away with commercial bondsmen. Instead of paying a nonrefundable fee, defendants can pay the court 10 percent of their bail, which they'll get back when they return for court.

And in New York City, Mayor Bill de Blasio recently announced an initiative that includes $17.8 million to expand supervised release pilot programs in Queens and Manhattan to the rest of the city. In addition, the New York City Council earmarked $1.4 million for a fund to bail out low-level offenders.

David Hill walked out of the Spokane County Jail into the blustery night on Sept. 2, just in time to catch the last bus to Airway Heights. Earlier that morning, he pled guilty to a gross misdemeanor in exchange for his release. Hill got credit for the 11 days he spent in jail, two years on probation and now owes $700 fines.

During a phone conversation last week, he was working on stripping copper out of two scrapped air conditioners. He doesn't know how he's going to scrounge up enough money to pay back his fine. Starting in February, he'll owe the court $10 a month.

If he misses a payment or violates any conditions of his parole, his criminal record will continue to build, and it's back to jail, where the revolving door could close a little tighter this time.

"I don't know what I'm going to do now," he says. "I just want this all this to be done with and to move on with my life." ♦

Glossary

Bail: A promise to return to court, most often in the form of money. The right to be released from jail on the promise of returning for trial is guaranteed in the U.S. Constitution.

Bail bond: Typically a written promise from a bondsman to the court that the defendant will return when asked in exchange for release from jail. If a defendant doesn't show, the bondsman is on the hook.

Secured vs. unsecured bond: A secured bond is backed by money or property; an unsecured bond is not. A defendant released from jail on an unsecured bond did not pay any money up front, but is liable for the whole thing if he or she misses court.

Bondsman: Someone who writes a bail bond on behalf of an insurance company. Also known as commercial sureties, bondsmen typically charge 10 percent of the total bail amount as a fee for their services and might require collateral.

Bounty hunter: A person tasked with tracking down those who missed their court date after they were released on bond.

Habeas corpus: From the Latin "that you have the body." The phrase refers to a legal order to bring a person before the court to justify detention.

First appearance: The initial time a defendant appears before a judge. A judge will inform defendants of their rights and what charges they face before determining whether there is enough evidence to formally charge them. If there is enough evidence, the judge will then decide to release or set a bail.

Plea bargain: A negotiation between a prosecutor and a criminal defendant. Typically, the bargain includes credit for time already served in jail in exchange for release and possibly conviction of a lesser charge.

Warrant: An order authorizing a law enforcement officer to arrest, search or seize. If a person misses a court date, a warrant is typically issued for arrest.