Six decades ago, at the very start of the Swinging Sixties, around 13 percent of married American adults were in a second or subsequent marriage.

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, that figure has shifted. These days, the proportion of married adults who've been married before is closer to one-quarter, according to a 2014 study by the Pew Research Center based on U.S. Census data. Of new marriages, 40 percent now involve one or both partners tying the knot for a second or third (or more) time.

What does that translate to in practical terms? Well, if you're part of a married American couple under the age of 55, the chances are good — more than six in 10, in fact — that you have step-kin in your immediate family.

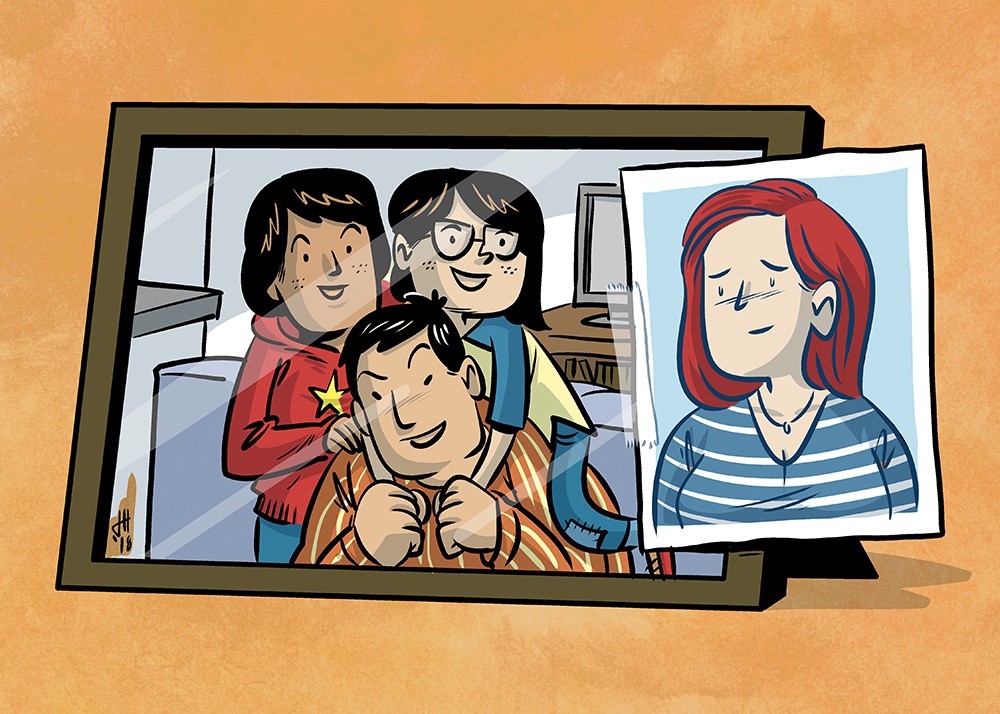

Even as increased exposure to divorce, remarriage and step-kin have softened societal attitudes, the act of bringing together, or blending, a stepfamily remains as challenging as ever. Stepparents have to negotiate an established family structure, with all its quirks and unspoken rules. Stepchildren have to contend with a new authority figure in addition to their biological parents.

Add to that the pressures exerted by the doubly extended family, potentially fraught relationships with ex-spouses, the general tumult of personalities and life and the mammoth task of blending becomes painfully clear.

"The hardest thing is figuring out your role in the family and coming to terms with it," says Andy Woodhull. "When you're the new person in the family, the kids are like, 'Who are you? You just got here.' I don't know what the rules are. They can say, 'Kids normally stay up till midnight,' and all I have to go off is that I don't think I got to stay up until midnight when I was a kid."

Woodhull is a nationally touring comedian who married into a family of three in 2013. As a way of coming to terms with his own abrupt transition from bachelor to stepfather to two young daughters, he started channeling his experience into his popular stand-up act as well as comedy albums like Step Parenting 2: The Teenage Years.

While Woodhull's self-professed "coping mechanism" as a stepparent dovetails with his career, many stepfamily experts consider humor an absolute necessity when trying to fuse individuals or existing families into a larger blended family.

"I'm a huge proponent of having a sense of humor," says Barb Goldberg, who maintains a blog with the tongue-in-cheek title The Evil Stepmother Speaks. She remarried as a single mom after "misplacing" her first husband, only to learn that her three stepchildren had dubbed her The Wicked One, something she says isn't helped by the archetype — think Cinderella and Hansel and Gretel — of the stepmother as villain.

It was her ability to find the lighter side that helped Goldberg roll with emotional setbacks instead of succumbing to fear, which she sees as a serious threat to remarriages.

"A stepfamily is almost rooted in fear from the start," she says, citing potential issues like financial uncertainty, emotional and practical expectations, sibling and partner rivalry, residual divorce guilt and exes' varying and sometimes unpredictable levels of involvement.

"Like many things in life, most of us go into [remarriage] believing that we're the exception. When you're dating someone, some of these things may not necessarily show themselves until you're in it. You love this person and this child or children, it's great, and then things start to come up," Goldberg adds. "That's really what drives a lot of the drama."

According to Ron Deal, an internationally recognized expert on blended families and author of Daily Encouragement for the Smart Stepfamily, among many other related books, Goldberg and other stepmothers often have a steeper hill to climb.

"Moms still expect of themselves — and society tends to expect moms — to be the emotional hub of the home. When stepmothers try to step into that space with children who have a biological mom who's very much involved in their world, there's no room for the stepmother, and the biological mother feels highly threatened by the stepmother's efforts. Now there's this battle over territory in the child's heart," Deal says.

However, stepmothers certainly aren't alone in dealing with complex emotional dynamics. Just as with biological families, territorial battles and jealousy are common points of contention. That's why both Goldberg and Deal say that holding out hope for a "full blend" while accepting the far more demanding reality is the first step when forming a stepfamily.

"Most stepfamilies honestly do not ever arrive at a full blend," Deal explains, "but my contention is that they're still a family. They're a family on day one, but they're a family in process. What they might not understand on the front-end is that it's very much a journey to arrive at [a full blend]. It requires a great deal of time and effort."

Forcing the matter — and the inevitable frustrations that entails — is typically what causes the most pain.

"You cannot demand or insist on love," he says. "What you can do is create an environment where love can happen. Now, that can be a little hard to swallow, because the stepparent is paying for everything, taking the kids to school, making tons of sacrifices. You can do everything right and they still don't let you in. Part of the trick is embracing who you are today, knowing that time and energy and love will deepen those relationships tomorrow."

Deal draws a comparison between slow cookers and smoothie blenders. The former allows the ingredients and flavors to mingle with time over a low heat. The other uses sharp blades to puree everything quickly into a homogenous whole. He advocates for the "slow cook" approach to stepfamilies.

The barriers to family blending can sound numerous and daunting, but patience and perspective pay off, Woodhull says. His now-teenage stepdaughters might not share his genes, but he sees his own idiosyncrasies reflected in their behavior — such as when they order Chinese food after being told not to order out for pizza, or when they circumvent the "no TV before homework" rule by sitting on the sofa in front of a blank screen.

"They are becoming incredibly literal smartasses," he chuckles. "That kind of stuff is infuriating, but I have to laugh because I like to think they get a little of that from being around me."