Menashe tells the gentle, carefully observed story of a man caught between strict social constructs and his own paternal instincts. Its basic building blocks suggest the sort of plot we've seen many times before, but its vivid backdrop makes this one different: It's set in the bustling Orthodox Jewish community of Brooklyn's Borough Park, and like many of its inhabitants, it never steps beyond the perimeter of the neighborhood.

One of the great joys of going to the movies is experiencing worlds and cultures few of us have seen, though Hollywood rarely affords us such pleasures. Menashe is the narrative debut of director Joshua Z Weinstein, whose résumé thus far has been dominated by nonfiction features and shorts. Despite being scripted, Menashe has a documentary-like shagginess to it, and we sometimes get the sense that we're watching not actors but real people caught on camera. It's surprisingly tough to manufacture authenticity, but Weinstein pulls it off.

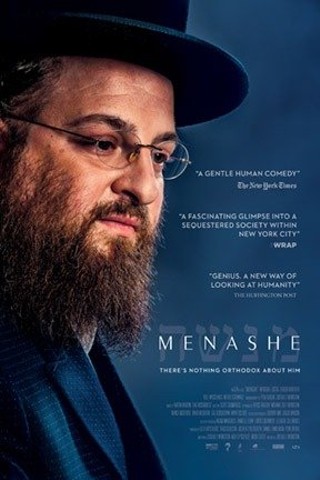

The film's title character, played quite well by first-time actor Menashe Lustig, is an Orthodox Jewish widower. He's rumpled, often harried, a bit impetuous, but no doubt well-intentioned. He works in a kosher grocery store, where he never seems to be on the manager's good side, and he spends most of his evenings alone in his sparsely furnished apartment. He's serious about his faith, but his own beliefs seem slightly at odds with those of his elders, though the film thankfully never defines or diagnoses his personal doctrines.

Menashe's young son is now living with his late mother's brother, and he will not be permitted to move back in with his father until he remarries, likely with the aid of a matchmaking service. ("Gentiles have broken homes," someone explains.) Menashe also balks at the strictness with which his former brother-in-law runs his household; the brother-in-law, meanwhile, argues that Menashe didn't adequately care for his wife while she was sick. Because we've only met Menashe in the aftermath of her death, this may very well be true.

When it comes time to put on a memorial for the anniversary of Menashe's wife's death, he demands it be at his place, even though doing so would deviate from custom. Whether Menashe's soft-spoken rebellion is a symptom of his personal hardships (or the other way around) remains something of a mystery, but the film itself is neither critical of Hasidic traditions nor Menashe's divergence from them.

You've no doubt seen elements of this film elsewhere — the notion of a somewhat hopeless single father attempting to win over his own child is territory that has been explored before — but the world in which it's set feels real, lived-in and genuine. And while there's an inherent fascination in documenting a world that's unfamiliar to so many of us, Menashe isn't exploitative of its central environment, nor has been made with the prying eyes of someone merely trying to make an anthropological study of Orthodox Judaism.

That's an important distinction, because Menashe is ultimately a film about personal empathy. This is a small film, played in a minor key, but it has something important (if not too terribly groundbreaking) to say. ♦