The Olympics are just under two months away. That means that right now, in gyms and stadiums, on tracks and fields around the world, thousands of athletes are punishing their bodies to whip themselves into the best shape humanly possible by the time the torch is lit in London.

But that also means that right now, in gyms and stadiums, on tracks and fields around the world, countless athletes are tearing muscles, cracking bones and snapping ligaments as they fight for a spot on their country’s team.

That’s where Jeni McNeal comes in. An exercise science professor at Eastern Washington University, McNeal is working on new ways to detect injuries in athletes, and to help them recover from the rigorous training necessary at such high levels of competition.

McNeal knows the tragedy of injury hampering a young athlete’s dream. She got into gymnastics at age 15 and quickly ascended to the level just below elite competition. But within a year, she injured her knee and spent the remainder of her career in constant rehab. Since then, she’s had 11 surgeries on that leg.

So McNeal wondered: What if there was a way to check for such injuries before it was too late?

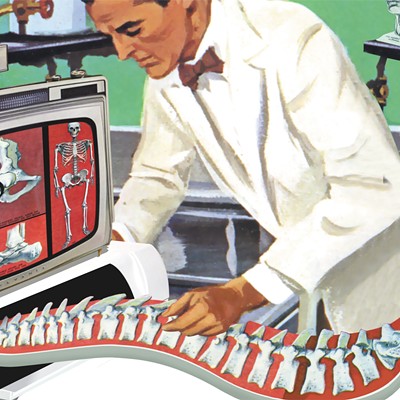

Until now, athletes, their coaches and their teams have simply had to wait until an athlete said “ow” — or, worse, until catastrophic injury took them out of competition — before they could diagnose an injury. But in research she chronicled in a new paper this year, McNeal and a colleague from the Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs used thermal imaging to see weak spots that naked eyes and X-rays could never detect.

“It’s something that’s been used in trying to early-detect breast cancer,” McNeal says. “It’s the same kind of technology that they use when they’re doing an energy audit of your house. Maybe a little souped-up version of that. They also use it in engineering, when they’re assessing fatigue in bridges and other structures, leaks in pipes, things like that. Anything where there’s a temperature differential.”

At the Training Center (where she works with the U.S. Dive Team), McNeal put several Olympic athletes in front of her camera.

The pictures were clear. In areas where an athlete had been injured, you’d see lighter-colored marks, indicating that it was a little warmer there than in the surrounding area. That’s because the body is trying to heal itself, sending more blood to the area and otherwise acting like a busy reconstruction site.

In her office in Cheney, McNeal wrenches her computer monitor around to show off the results.

“So this is a gymnast right here, and there are definitely areas that you would normally find as hot, but lower here on the back, you can see this is where the back of the hip bone is on either side, and then this right here is a lower-back problem that he’s been having.

“And then this is one of our Olympic sand volleyball players, a very famous one, who’s had a lot of back problems through the years. In this case, it’s an SI [sacroiliac] joint problem, rather than a lumbar spine problem.”

In another image, a male athlete sits flat on the ground, thrusting the bottoms of his feet into the foreground of the image. The one on the right is a normallooking gray. The one on the left is pure black — the result of poor circulation or nerve damage.

The thermal imaging technology, McNeal says, is helping to solve cases that had fallen through the cracks, leaving the athletes’ trainers and doctors at their wits’ end.

“The physicians we’ve worked with … get really into it and enthusiastic about it, because it gives them just another way of seeing that they can’t see with their other tools,” she says. “And of course we don’t charge them for anything, so that’s a free diagnostic.”

Of course, there’s still more work to be done. So far, McNeal’s work has been mostly qualitative. What she needs now, she says, are quantitative surveys of injuries — showing, say, what a sprained ankle looks like in the thermal camera on Day One, Day Two, Day Three — so that they can better track and diagnose injuries as they happen.

And the information can also be a double-edged sword. What if you were an aspiring Olympic diver, a month away from the Olympics, and one of McNeal’s images showed a strange abnormality in your back? Your coach might sideline you, to prevent injury and to strengthen the team. But what if it was nothing?

McNeal says it would take culture changes at the highest level of sport.

“It’ll require buy-in,” she says. “And there has to be some sort of protection for the athlete, so that just because an injury has been identified doesn’t necessarily preclude them from being chosen for things. It has to be encouraged and promoted by the administration as a good thing.”

McNeal’s research on thermal imaging was only one of two projects she published papers about this year. She’s even more excited about her “squeezy pants.”

McNeal explains that when athletes are recovering from difficult training, their muscles and other tissues, in the process of rebuilding, slough off cellular debris. Luckily, our bodies have natural pumps that squeeze those byproducts up toward our guts, through the filters of our kidneys, and out into the toilet.

High-performing athletes, however, need to accelerate that process. Thus, the wealth of compression socks, compression pants, compression everything on the market.

But McNeal believes such apparel doesn’t go far enough, because it only holds everything in, statically, and it eventually wears out.

Enter McNeal’s “squeezy,” or “peristaltic pulse compression,” pants.

To demonstrate, McNeal slips on one leg of what looks like a pair of giant black puffy ski pants — “just to give you kind of an idea of how funky they look.” She throws the swaddled foot up on her desk, along with a chunky compressor the size and shape of a car battery. Using the compressor, she can control the pressure of each of five compartments in the leg of the pants, which squeeze in succession from heel to hip.

The pants squeeze considerably harder than any masseuse could, she says. “I can’t liken it, really, to anything. But what is interesting is when it partially decompresses, you feel an immediate rush. I mean, you can feel the sensation of warmth and flow, from wherever it was just released.”

In studies at the Olympic Training Center, McNeal would have athletes wear the pants (or a set of squeezy arms) for 15 minutes after each of their two workouts for the day, then she’d test their resistance to pain in the areas where they were the sorest (so, say, the quad and calves of an Olympic sprinter). Those who had gotten the squeezy treatment, she reported, showed far greater resistance to pain than those in a placebo group, who had worn the pants without turning on the compressor.

Both the compression pants and arms have been commercially available for years (Lance Armstrong has championed them, and some professional cyclists swear by them), but as she did with thermal imaging, McNeal was among the first to apply their strengths to athletic training and recovery.

She says there’s a lot more research to be done, but as a regular entrant into extreme adventure races, she’s just happy to have a pair of her own for now.