When it comes to paleontology, the most exciting discoveries aren't always made in the field. Sometimes, they're made in a windowless museum basement lined with cabinets full of bones.

That's where John Orcutt was around 2008, pursuing a Ph.D. at the University of Oregon and paying the bills with a job inventorying fossils at the university's Museum of Natural and Cultural History.

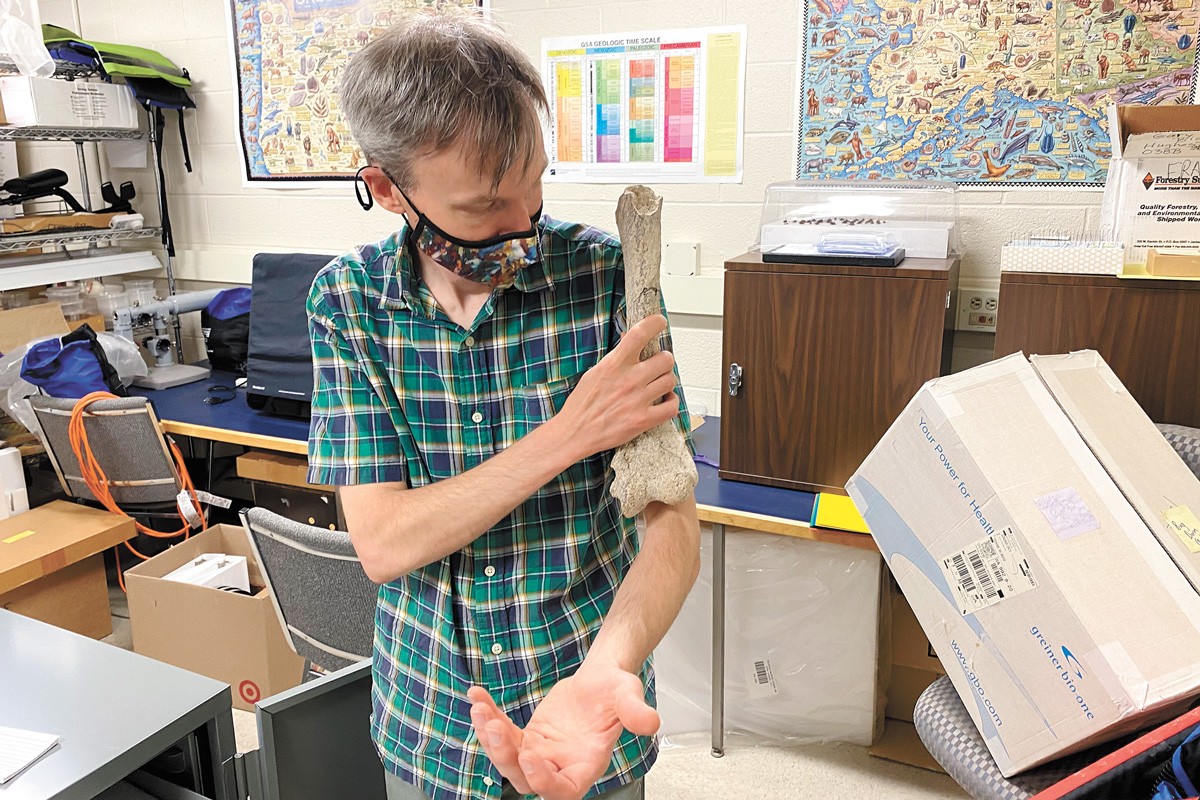

Orcutt, now an assistant professor of biology at Gonzaga University, was going through cabinets when he came across a lower arm bone labeled "felidae" — the scientific word for cat. The specimen was discovered in the 1950s and had been collecting dust in the basement cabinet for decades.

"John saw it and was like, 'No way. That's way too big, that's not right,'" says Jonathan Calede, Orcutt's office mate at the time who would later co-author a research paper about the cat with Orcutt.

Because of its size, Orcutt initially thought the bone might have belonged to a rhino or a bear. But upon closer inspection, Orcutt realized the bone might belong to a previously undiscovered species of saber-toothed cat.

Over the next few years, Orcutt found more large cat bones at other universities that further cemented his hunch. In 2017, Orcutt and a team of three graduate students revisited the field site in Eastern Oregon where the bone in the museum collection had been discovered. In a stroke of luck, the first bone they found was an arm bone that belonged to the same large cat species.

"I knew in a second exactly what it was," Orcutt says. "It's a dead ringer in almost every way."

Calede helped Orcutt run a quantitative analysis comparing the bones with other, previously discovered saber-toothed species. In May 2021, the pair published a paper outlining their findings and confirming Orcutt's hunch from more than a decade ago: There's a new cat in town, and it's name is Machairodus lahayishipup.

The first part of the name comes from the Greek word "dagger teeth" and identifies the genus that includes a half-dozen other saber-toothed cat species. For help coining the second part of the name, Orcutt turned to the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation upon whose traditional lands some of the bones were found. "Lahayishipup" is a compound of the words "ancient" and "wildcat" in the Old Cayuse language.

One of the most striking things about the cat is its size. The average M. lahayishipup weighed about 600 pounds. The largest bone analyzed by the pair belonged to a cat that was around 900 pounds, placing it among the largest cats in recorded history.

"When John was talking to me about where he was going with that project, even before I was involved in it myself, it was very clear: They're huge," Calede says. "You're like, 'Oh, that's a very, very large cat. It shouldn't be the size of a bear. What's going on?'"

Saber-toothed cats have been discovered before in North America, but the majority are from the last million or so years. The species documented by Orcutt and Calede is from 5 million to 9 million years ago.

Saber-toothed cats earned their name and reputation from lengthy, dagger-like front teeth, but Orcutt says there's debate in the scientific community about what those teeth were actually used for.

"The teeth are really long, but they're also really narrow and surprisingly brittle. So it seems unlikely that they were slicing into mammoth underbellies with those teeth, because you're asking for trouble if you do that," Orcutt says.

So instead of using their sabers to attack, Orcutt says saber-toothed cats may have instead used their beefy forearms to grapple with prey — sort of like how a modern house cat plays with a toy. Once the prey was restrained, the cat would have used the sabers to deliver the killing blow and slit the animal's throat.

"They are the final straw on the camel's neck," says Calede.

Camels were common in North America in M. lahayishipup's time, and these grazers had reason to fear the big saber-tooths. Rhinos and giant ground sloths were also probably on the menu, Calede says. Because of the cat's large arms, the scientists think the cat was an ambush predator who stalked prey until it was close enough to pounce.

Orcutt says that if he could travel back in time and see M. lahayishipup in person, he would be most interested in observing how the cat hunted. Did it roam in packs like the modern lion? Or was it more of a solo predator like a cougar?

Calede takes a more pragmatic view: If he were able to observe the cat in the wild, he would be most interested in finding a place to hide and not get eaten. ♦