On a cold February night, snow is falling in short spurts. A man lies bloody in the middle of the street.

Do you stop?

In Spokane last month, multiple drivers didn't. Not the first driver who hit him and not at least two others who hit him afterward. Neither, presumably, did any number of cars that passed by the scene until, at some point, a man finally did. A dozen officers arrived; someone covered the victim with a yellow tarp.

Just a year earlier, an 8-year-old boy fell into a frozen Spirit Lake during a town festival. A local high school student, Jason Cole, leapt in and pushed the boy up onto the ice. Cole left the scene without telling anyone what he'd done until his parents asked why his clothes were wet. A month later, when he was recognized at an awards ceremony, Cole said simply, "I didn't want to see him die."

The two cases raise a question: In our most desperate and vulnerable — bloody on a dark, cold roadway, or gasping in a frozen lake — can we count on each other?

It's a question that touches nearly every corner of our society. Should you help a stranger on the street? What separates the person who does from the one who passes by? What do we owe a neighbor, or a victim of a faraway war or famine?

What is worth setting self-interest aside and what is simply not compelling enough?

The idea of helping others is a particular paradox in a nation built on individualism, and it's resurfaced time and again in our national identity: Ralph Waldo Emerson's self-reliance, Ayn Rand's The Virtue of Selfishness, so-called "social Darwinism" as a justification for inequality, Milton Friedman's argument that any business' sole social responsibility is to "increase its profits."

There may be no universal answer for what we owe each other. It's a question rooted in your own personal code. But if our world is as brutal as we know it to be, how can we explain kindness?

And if we can understand the drive to help, can we also encourage it?

The police and medical examiner's reports paint a gruesome picture of the hit-and-run on Mission Avenue on Feb. 9. Paul Taylor, one of the officers investigating the death, says images like that stick with him "like snapshots" he can see long after he leaves a scene.

"I look at it like a bucket and more stuff gets piled in there, and there's only so much that that can hold," he says. "That snapshot is there, and it's not pretty."

Soon after his death, the identity of the victim was released: Don Foster, 55, homeless. But the police still don't know who hit him. (A recent suspect, a woman who lived nearby, was cleared.) Police say the investigation is still a top priority, but these cases can be hard to solve. In 2009, a Spokane woman was hit by a car and dragged 15 blocks near North Ash Street before the driver fled. Police have still not found her killer.

Hit-and-runs are not the norm — nationally, they make up about 5 percent of traffic fatalities — but they're not the only instances of seemingly cruel indifference. Indeed, there is a whole class of horrific crimes in America that have become case studies of our humanity — or lack of it.

Early one morning in 1995, a man dragged a woman from her car and beat her on a Detroit bridge after a minor auto accident. Two other men smashed her windows with a crowbar, as traffic backed up and onlookers stood by. (While early reports indicated the onlookers were cheering, police later disputed that claim.) Eventually, the woman fell from the bridge into the river below and drowned. Whether she was pushed by her attacker or leapt in fear of him remains hazy, but her body was later found, missing one leg, apparently severed by a boat propeller.

"I wanted to help her," one witness told the Associated Press, "but I was simply afraid."

In 1964, Kitty Genovese, an independent 28-year-old bar manager, was walking home from work in Queens, N.Y., when she was stalked and attacked by a stranger. He stabbed her multiple times over the course of a half hour as she stumbled down the sidewalk trying to escape him. For many, what was even more shocking was a New York Times report that 38 witnesses had watched from their apartment windows while only one had called police. One witness reportedly said later, "I didn't want to get involved." The story — told and retold — struck a nerve, begging questions about our own allegiances to each other and the coldness of big-city life.

In the years since Genovese's murder, it's become clear that it's likely only a few people actually saw the attack and at least one yelled at the man to leave. The 911 system didn't exist when Genovese was hunted through her neighborhood and relations between police and citizens were tense. It's likely the few who might have seen something weren't completely sure what was happening or how to help.

Yet the research born of Genovese's death has held up. Studies have shown that the more people are around, the less likely any one individual is to step in, a phenomenon known as the "bystander effect" or the "diffusion of responsibility."

We think "surely somebody is going to go take charge. I don't need to do it," says Craig Parks, a psychology professor at Washington State University who has researched helpfulness and cooperation. "The problem is everybody else is thinking the same thing."

So what separates the person who intervenes from the bystanders?

Parks says humans will consider four basic questions before they offer help.

1. Is the person clearly in distress?

2. Do I know what to do to help?

3. Am I physically able to offer help?

4. Does the benefit of offering help outweigh the risk to me?

"If any one of those is not met, the person is just not going to get in there," he says.

Once those questions are answered, the reasons we help vary and are, psychologists say, often self-interested: Another's suffering makes us uncomfortable and acting to help alleviates that discomfort; we'll feel guilty if we don't help; we anticipate the rewards, whether in recognition from others or self-satisfaction; or we simply want the vicarious happiness that comes with seeing another person happy. In contrast, pure altruism — if it exists — is helping solely for the purpose of another's well-being.

David Schroeder, a University of Arkansas psychology professor who's currently editing a "handbook on prosocial behavior," says nearly all instances of helping likely come from an egoistic place. It takes intense feelings of closeness and empathy to act truly selflessly, and those feelings are rare, especially toward strangers, he says. While some psychologists say the distinction between altruistic and self-interested helping matters, Schroeder says, "The nice part is whether or not it's egoistic or altruistic, the victim is being helped."

Of course, there's no way to know what went through the minds of the drivers who hit Don Foster. We don't know what they saw, how much they knew or what they perceived as the risk to themselves. Parks says it's not unlikely, in those types of situations, to try to rationalize what just happened.

"The notion that I just ran over a human in the road is pretty incomprehensible to a lot of people," Parks says. So the drivers may have thought, "It's so hard for me to fathom, it's so unbelievable, that that can't be what happened. I must have run over a pile of rags or something big that fell off of a truck. What happened was so unbelievable they chose not to believe it and came up with an alternate story for what happened."

Last year, the Pittsburgh-based Carnegie Hero Fund recognized a Florida woman who pulled a woman and child from a burning SUV just before the entire vehicle was engulfed in flames.

That same year, the fund recognized a man who saved a neighbor from a stabbing, a teenager who pulled a boy from a river and several others who saved people from burning buildings and cars.

"No, they are not hard at all to find," Carnegie Hero Fund Commission President Walter Rutkowski told NPR's Radiolab about nominations for the award, which recognizes people who "risk their lives to an extraordinary degree saving or attempting to save the lives of others."

"Regardless of what you hear elsewhere, we are fortunate to be living in a society where people do look out for others, even strangers."

The Eastern Washington Region of the American Red Cross gives out about a dozen awards a year to "Hometown Heroes." Some are recognized for dedicated community service over the long term and others are first responders expected to act to save others on the job, but others are "everyday" citizens who take lifesaving action. In the past few years, the awards have gone to people like Jason Cole, the teenager who pulled the boy from Spirit Lake; a man who chased down and tackled Avondre C. Graham, who had attacked a woman on the Centennial Trail; and a woman who, after two sheriff's deputies were shot in North Spokane, held pressure on one of the officer's severed arteries, keeping him from bleeding to death.

The Spokane Fire Department awards the Citizen Community Life Saving Award and has in recent years recognized a man who pulled an elderly woman from a burning house, a high school student who pulled an unconscious woman from traffic and citizens who've performed CPR on strangers.

"I couldn't generalize why each one feels the need to help," says local Red Cross spokeswoman Megan Snow, who helps find nominations each year, "but it's just something, and it's pretty amazing to see."

Even the bravest among us don't necessarily know why they help.

After Tomi Wheeler held pressure on the sheriff's deputy's wound in 2012, she told KXLY she saw "no other option."

"You may think I'm a brave person," she said. "I was just doing the right thing at the right time."

The question of whether altruism can be pure has persisted at the junction of science and morality, and tortured its share of scientists and philosophers.

In a life detailed by writer and professor Oren Harman in The Price of Altruism, George Price is a tragic example. A scientist whose work ranged from the Manhattan Project to cancer research, Price began in the 1960s to ask a question others were wrestling with at the time: If the world is truly explained by survival of the fittest, why does anybody help anybody else?

He developed the so-called "Price equation," which built upon other scientists' work to explain how altruism evolves, driven by the desire to preserve one's own genes. When Price presented the equation to a University of London professor, he was given an honorary professorship and office. But he wasn't satisfied. If kindness could be reduced to a survival instinct, then nothing could ever be true altruism. It is all, in the end, in the interest of the self, and what kind of world does that leave?

In hopes of proving his own math wrong — of proving true kindness could exist — Price took on a life of "radical altruism," giving his money away to homeless people on the street and inviting them into his home. Soon, he had given away all of his cash, but was still unsure whether he had actually been altruistic. Is there any way to escape the self-satisfaction of doing good for others?

In the end, Price remained unconvinced, according to Harman. Price saw little change in the behaviors of the people he helped, and he remained far from his daughters, whom he had abandoned at a young age in search of a grand discovery. He was homeless and unwell, physically and mentally. At 52, he cut his own carotid artery with a pair of small scissors.

On a slip of paper found with his effects was this:

"Men and women have always yearned for understanding, compassion, forgiveness, and deeds of loving kindness from their fellowmen, but often they've been sadly disappointed. And today more than ever in a world torn by strife and dissension, the crying need is for a real demonstration of love. You see, love would pour the oil of quietness upon the troubled waters of human relationships, heal the ugly wounds of strife and contention, and bring together those separated by hatred, jealousy and selfishness."

First comes the call for help. The splotches, like raindrops on a windshield, wiggle and gyrate until they're all in a big mass, wiggling as one.

Meet Dictyostelium discoideum, a single-cell, bacteria-eating amoeba that's known to sacrifice itself for the greater good.

When food is plentiful, dictyostelium acts completely independently, but when it's scarce, things change. A group of dictyostelium morphs into a slug and finds a place that's warm and sunny. There, it sprouts a stalk with a bulb on top — picture a lollipop — which allows those amoebae that make it to the top of the stalk to catch an insect or gust of wind to somewhere with more to eat.

But those who make up the stalk, about 20 percent of the group, die, having sacrificed themselves for the rest. Dictyostelium seems to beg the question: If an amoeba can act selflessly, shouldn't we be able to as well?

First, a note of caution. Altruism among amoebae is not the same as altruism among humans. With no brain or central nervous system, an amoeba cannot make the conscious decision to be helpful. It is not willfully sacrificing for others.

Still, the presence of altruism in organisms like dictyostelium — which cooperate and can be easily manipulated in a lab, unlike most other social insects or animals — allows us to explore old questions in a new way. While biological findings about amoebae won't explain human kindness, there are "philosophical implications," says Gad Shaulsky, a genetics professor at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston who has studied, among other things, "cheating" in those dictyostelium that avoid death.

"We can infer that in the human condition, we will never have a perfect altruist because the perfect altruist will eliminate itself. We will always have this struggle between selfness and selflessness," Shaulsky says.

"The analogy to the cell deciding, 'Am I going to be spore or a stalk?' is the same principle, just a lot more exaggerated and easier for us to experiment on. It's a great way to start conversation."

While some scientists argue we're hard-wired to be kind, others believe that even our tendency toward helping evolved to preserve our own genes and true altruism doesn't really exist. The two may not be mutually exclusive.

Frans de Waal, a well-known primatologist, argues that the reasons behaviors evolved don't necessarily dictate how they're used. Just because kindness may have evolved in self-interest doesn't mean all kindness today is self-interested.

In fact, working together in communities is ancient and deeply ingrained, de Waal writes in his latest exploration of the issue, The Age of Empathy. Like fish swimming in schools, we know we're safer in cooperative groups, so violence and a disregard for others may not be as inevitable as we may think. Take the behavior of chimps and bonobos, two of the primates to which we are genetically closest. Chimps violently raid their neighbors and kill their enemies. But when confrontation begins among bonobos, females rush to the enemy camp and begin having sex.

"Since it's hard to have sex and wage war at the same time, the scene rapidly turns into a sort of picnic," de Waal writes. "It ends with adults from different groups grooming each other while their children play."

Empathy may begin not in our minds, but in our bodies, according to de Waal. Laughter and yawning are contagious. We're physically connected to other humans before we ever begin to consider their plight. It explains why we wince when we see someone else slam their finger in a car door or teeter precariously on a tightrope.

Even mice seem to feel each others' pain. When placed in clear tubes (so they could see each other) and injected with an acid to give them a mild stomachache, mice who could see a fellow mouse stretching from the discomfort would express more discomfort than one who was blocked from seeing others or whose companion wasn't given the acid. The reactions were also stronger between mice who were cage mates than strangers.

The usefulness of all this, outside of furthering research, is in finding ways to encourage more selflessness.

Researchers disagree about how much our motivations for helping matter if the person in need receives the help either way. But if we can understand our reactions and impulses, can we make ourselves more helpful?

For Ken Applewhaite, another officer investigating Don Foster's death, the appeal is the call for empathy we've been making for generations. Helping is the price we all pay to belong to a community.

"My thought on not getting involved is this: It's something that's easy to say until you are the one that needs it," he says.

In the research, there's more nuance. WSU's Parks has found we may be discouraging others' kindness. When research participants were given descriptions of fictitious strangers who were generous and involved in various community activities, they were asked to describe what they would expect if they were to meet the people. Nearly half of the participants used negative descriptors: arrogant, naive, know-it-all. When Parks published the study in 2010, he says he got dozens of emails from people who said they'd experienced similar reactions in their workplaces.

"That's too bad if you think about it," he says. "These are the people we shouldn't be trying to squelch."

In Spokane, city leaders are pushing citizens to step up.

In an announcement at Riverfront Park this month, Mayor David Condon called on the city to step up its volunteerism, announcing a new website to pair citizens with volunteer opportunities. People in Spokane want to help, the mayor said, and the city would now make it easier for them to do so.

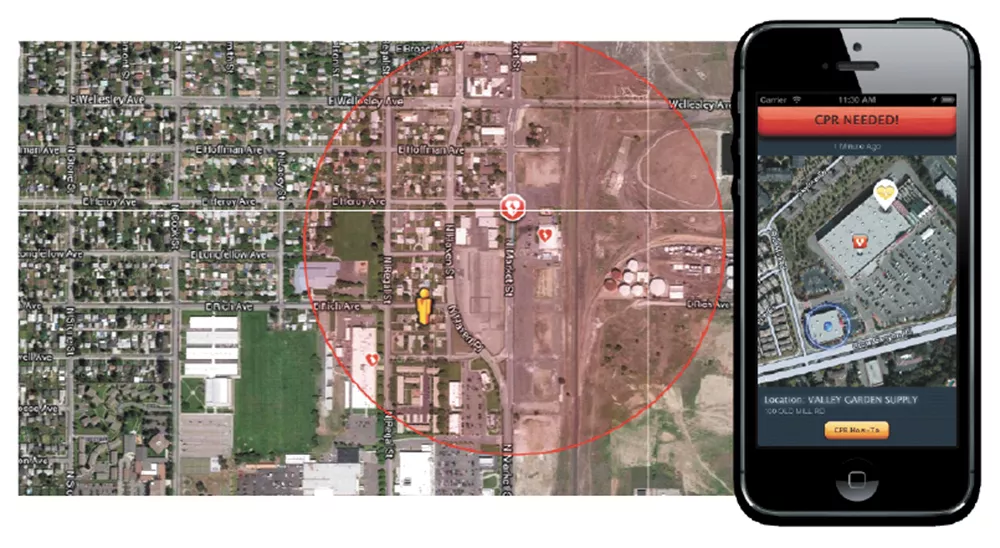

The Spokane Fire Department's call is even more urgent. The department has begun using a national app, PulsePoint, which notifies people who are CPR trained and have the app when someone nearby is experiencing cardiac arrest so they can respond. (The app's catchphrase: "Enabling citizen superheroes.") It's at once an effort by the department to save lives and a bigger social experiment. So far, about 1,100 people in the area have installed it, and a few have responded to calls, says Assistant Fire Chief Brian Schaeffer.

"I wish everybody had this app — every high school kid who carries a phone in their pocket, every Avista driver — so the system would be saturated with responders," says Schaeffer.

Emma Seppälä, associate director of Stanford's Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education, says the power to spread kindness is not out of our reach.

She doesn't shy away from the benefits we can receive from helping others. Selfishness in that regard is not necessarily a bad thing. Stress can be one of the main reasons we ignore others, she says, so relaxation like meditation can push us to look outward, making us more social and caring. And seeing someone else who's social and caring may be all we need to change ourselves.

"It's a ripple effect," she says. "Others learn from seeing you. It can be shocking to people sometimes to see an act of compassion. They'll say, 'Why are you helping?' but shocking people in that way is educational. It shows you have a choice." ♦

If you have information about the Feb. 9 hit-and-run on Mission Avenue, call Crime Check at 456-2233.