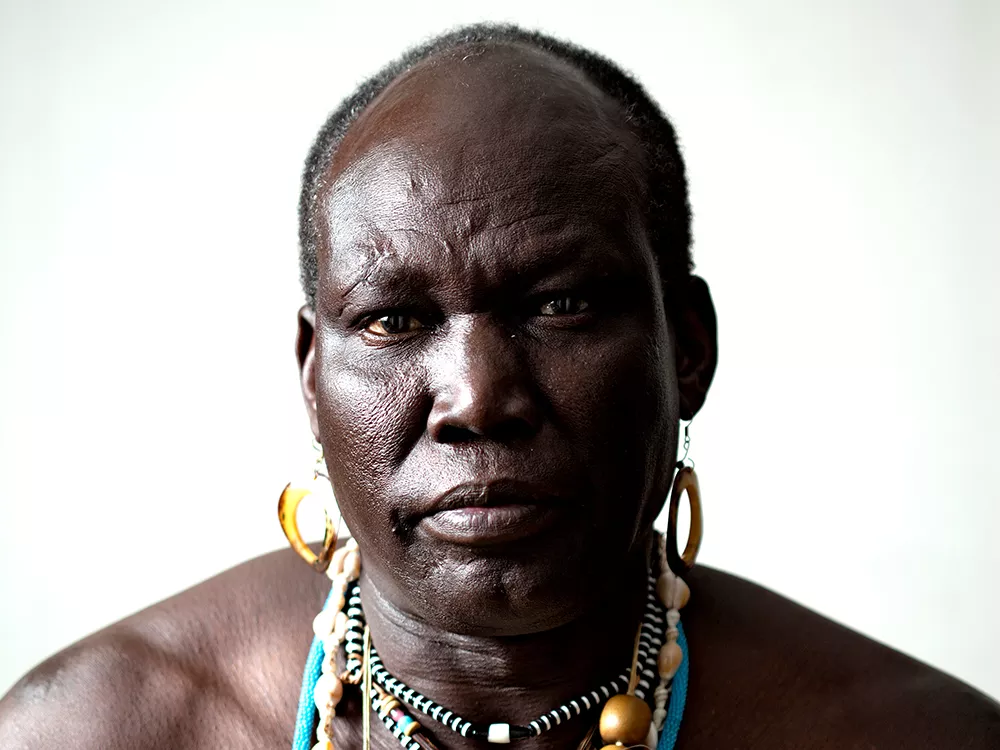

By all rights, Agwa Taka should be dead.

If starvation didn’t get him as a kid in Ethiopia, then disease, three wars, childhood slavery and a year in a hellhole prison certainly should have done the job.

But here he is, up at 1:30 every morning, drinking a cup of coffee, the snow melting outside his kitchen window and cars passing in the distance on Grand Boulevard. Agwa (“AWG-wah”) listens to the news on the radio. He pets his dog Rosco, filling his bowl with kibble as the mutt looks back at him with a tonguey grin. He pulls on a pair of jeans, hiking boots and a polo shirt.

In the dark, he maneuvers his bright red pickup truck down the South Hill, up Division, through East Spokane, past car dealers and grocery stores and taverns. At a gate, he swipes a card and parks behind a warehouse.

Inside he punches a timecard, stashes lunch in a fridge and walks onto the warehouse floor.

By all appearances, an average man with an average American life.

But in a place of big dreams where men are considered exceptional for what they have or what they’re known for — for their wealth or their power — for some it is enough to have simply survived the ordeal.

As Agwa stands on a factory line, the memory of what he’s been through will sometimes come rushing back. He thinks about how the people he works beside each day have no idea. He wonders then: Does the world see him as just a man with a truck, a dog and a warehouse job?

If it were only that simple.

I

No one knows how old Agwa Taka is.

He comes from a place that tracks the number of times the moon has risen with knots on a rope.

As a boy, Agwa watched his mother scan the night sky for a full moon. When she found it, she would tie a small knot in a thin rope hanging from the back of their hut. She checked the rope when Agwa, the youngest of five, asked how old he was. As she counted the knots, she recalled that he was born a few days before a famous man was murdered. Even in this remote corner of Ethiopia, she had learned of JFK’s assassination, but she still could not say definitively what day Agwa had come into the world.

She named him Agwa, a word meaning “identity.” It was a common name for village children who had lost a parent. Agwa doesn’t know which disease killed his own father, just that he was dead before Agwa’s birth. And by his mother giving him the name, she was telling other villagers: This boy needs your care.

Agwa comes from that Ethiopia, the one Americans know from heartrending TV commercials and National Geographic — the land of bloated bellies, a place that swarmed with malarial mosquitoes, a village where poisonous snakes hid underneath the thatched grass roofs of tiny mud huts. The Ethiopia where water was caught in plastic rain buckets, and food was hunted with sharp sticks.

His people are called Anuaks — a tribe of lowlanders populating the hot, jungle-bordering lands of western Ethiopia. In Agwa’s homeland, it was not good being Anuak. They were seen as dogs by highlanders, whose skin was just a shade lighter than that of the Anuaks.

During Agwa’s childhood, Anuak men who strayed from the villages were often abducted. Women were made into concubines, children were taken as slaves. Even now, Ethiopia remains a “source country for men, women and children” who end up in forced labor or prostitution, according to a 2010 U.S. Department of State report on human trafficking.

By age 6 or 7, Agwa hadn’t quite learned to be wary of strangers when a highlander teacher — a man named Melcamu — brought a chalkboard into his village of Gambela and gathered Anuak children under a tree to watch as he drew the letters of the alphabet. Agwa stared with wide eyes. The young boy followed his teacher like a shadow.

He doted on Melcamu like he was the father he never had — washing his teacher’s clothing, gathering his firewood. He prepared his tea. In his young mind, he thought that the more time he could spend with him, the more of the teacher’s vast knowledge he could absorb.

When time came for Melcamu to leave Gambela, he asked Agwa’s mother if he could take Agwa along. In exchange for Agwa’s service, the teacher promised to educate the boy. Agwa’s mother refused. She knew what highlanders did to Anuak boys.

But on the day his teacher was to leave, young Agwa walked from the village on a long dirt road, waiting for his teacher’s car to pass. When it did, Melcamu opened the door, and Agwa jumped in.

As the car carried him 300 miles away from the only place he’d ever known, Agwa had a feeling that this man was a magician of some kind, someone who could teach him things he never would learn in Gambela.

He remembers feeling like this man was a bright light, a beacon shining into this forgotten corner of the world.

II

On a snowy winter afternoon, sitting in a Starbucks high on Spokane’s South Hill, it’s so clear to Agwa that his life could have been cut short then.

Of course it’s easy now to see what a highlander man wanted from a little Anuak child. Hindsight is 20/20.

But then, tempted by a teacher’s promises, how would he have known?

As a boy, Agwa’s naïveté deceived him. It made him follow Melcamu. It made him believe in people. And it made him think he was an exception to the tales he’d heard of Anuaks being plucked like low fruit on a tree — snatched out of villages to be slaves.

Of course, today Agwa knows the reality of child slavery in Africa. When families send their young children out to work in fields or homes to supplement the household income, they’re often exploited because of that naïveté. A 2005 United Nations report found that more than 58 percent of Ethiopian boys between the ages of 5 and 14 were child laborers. “Child domestics work long hours and are vulnerable to sexual abuse,” the report reads. “Many are unable to attend school and are unpaid, receiving only room and board.”

But back then, it took years for Agwa to realize he was one of those statistics. At first, his teacher kept his promises. In his home on the outskirts of the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa, he’d teach Agwa to read. In exchange, the young boy would make him tea. He showed him to write, and then Agwa would cook.

One day after Agwa learned to read, he found a letter in his teacher’s clothing from Agwa’s own stepfather. It begged the teacher to “bring my child back to me.” The boy ignored it.

As the weeks turned to months, and months to years, his lessons became less frequent and his work — cleaning, sweeping, washing, serving — became more and more grueling. It wasn’t until some six or seven years after Agwa got into his teacher’s car that he realized he was indeed a slave. He was chatting with a neighbor. She mentioned that other people talked of stealing him to be their own slave, jealous of Melcamu’s doting young Anuak.

At that moment, Agwa pictured another neighbor woman he’d met. She lived behind a building holding cows and horses, in a closet-sized space — her bed sandwiched between a stove and a large grindstone. There she lived and worked, never moving more than a few steps. Agwa noticed then that her knees were bound with rags, and scars crisscrossed the backs of her heels, where her Achilles tendons had been sliced.

Still, a part of Agwa, at only 13, wanted to believe he was an exception — that his teacher saw him as extraordinary. He pressed Melcamu for more education. After he did, he overheard his master laying out plans for the boy to be moved to a farm. In hushed voices, Melcamu said the boy was getting too smart. He must be tricked. Once they got him to the farm, they would cut Agwa’s Achilles tendons.

The next day, on his usual trip to buy food for his master, Agwa escaped. He just kept walking, for miles and miles, deep into the center of the bustling capital city. Alone, he would hide in the crowds.

III

Penniless, the teenaged Agwa slept in building corners and alleyways where no one could sneak up on him. When the sun rose, he went from door to door, begging for food and water. He offered to split wood for pocket change.

They looked at the boy’s inky black color and told him he should be a slave with skin like that.

When he had begged for enough money to buy a brush and a tin of shoe polish, Agwa crouched at the knees of travelers at the city bus station, buffing their leather shoes.

He had no idea what would come next. Would he see his teacher again? Could he find his way back home? How long would it be until someone else tried to make him a slave? He tried to be invisible. He trusted no one.

After months of polishing shoes at the bus station, Agwa overheard a word he knew: Gambela. A man had caught the wrong bus and was asking a driver when the next one was leaving for the small Ethiopian village.

Before he could think, Agwa rushed to the man’s side and begged to go with him to Gambela. The man, shocked at Agwa’s desperation, agreed to help.

After so many years away, when Agwa returned home to Gambela, he didn’t feel the sense of relief he thought he would. The village had changed. Maybe he had just changed.

As he hugged his mother — tears running down her face as she looked over the grown boy who stood before her — Agwa had the feeling that, while he was away, he lost something. Anuak words seemed jumbled, and hard for him to understand. The village didn’t look like he remembered.

He felt like a stranger in his own home. A bird that can’t find its nest.

IV

For someone who doesn’t like American coffee, Agwa drinks a lot of it. On an icy Friday afternoon at another Starbucks, by Gonzaga University, he sits at a corner table and talks over the scream of a nearby espresso machine and the chatter of college kids studying for final exams.

He says that back in his village, it was as if survival was always on his mind — like he was programmed to always think about the ways a situation might go bad, and how he might escape it. It guided everything, even when he was the age of these kids studying here today, he says.

As a student at Gambela’s high school, he remembers sizing up the female students, assessing their potential as his future wife. A good match, he explains, wasn’t about pretty smiles or a good personality. It wasn’t about who made you laugh. He needed a woman with tenacity — someone who could endure through the toughest droughts and protect their future children from the dangers of the jungle.

Still, he’ll never forget the first time he met Ariet Oman — a pretty Anuak girl. At their high school, everyone knew Ariet. She was the girl who’d been raised and educated from a young age by American missionaries. She could read. She could write. She could speak English. She walked with her head high. Ariet was not like other Anuak women — she was confident, outspoken, rebellious.

Though he liked Ariet, today he recalls thinking that her missionary upbringing wouldn’t make her a good wife. While so many Anuak had endured famine and disease, Ariet had been raised in a different world — one driven by American, not Anuak, values.

At the coffee shop, Agwa turns conversation to his own American-raised daughters — 19 and 21 years old — and what he had survived by the time he was their age.

“My kids, the age they are right now, it is the age I already experienced some of the reality and tests. And [made it] through,” he says. “When I look at them, I see that they haven’t gotten there yet. And they still are wandering.”

V

Agwa remembers being in class at his high school — a room with desks and books, not unlike an American high school — when soldiers barged in, asking for students to go to the warfront. Agwa looked around the room and was surprised when some of his friends hesitantly raised their hands.

Each week, more soldiers would come, and more students would leave. No one would return.

Unrest in Ethiopia was nothing new — the country had been in some conflict or another for most of the 20th century, fighting in the east against Somalia, in the north against the Eritrean Liberation Front, and within its own borders with its own people.

In 1974, the Ethiopian emperor was deposed by a Soviet-backed revolution, and a new dictator, Mengistu Haile Mariam, assumed power. At the same time, a civilian group called the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party (EPRP) was vying for control of the country. Mariam declared war on these counter-revolutionaries, ordering soldiers to do house-by-house searches across all of Ethiopia in search of EPRP members. When found, they were executed. This period became known as the Red Terror, and Amnesty International estimates that as many as 500,000 people were murdered.

Agwa recalls how the government tried to divide his own people, the Anuaks, telling them to fear those among them with education, and to resist against anyone who refused to fight.

Refusal alone came with consequences. Some were dragged by soldiers from their homes in the middle of the night and executed in front of their families as warnings to others.

But from the day he saw soldiers taking his friends to the warfront, Agwa refused to go — insisting to recruiting officers that he could not leave his mother to fend for herself.

Perhaps that was his first mistake. Or maybe it was that Agwa told his friends to use the same excuse.

One day, as Agwa returned home from fishing, he was told that a friend was being held at the Gambela police station and needed his help. Agwa, then 20, ran as fast as he could. At the police station, Agwa told the officers his name and who he was looking for.

“Agwa Taka?” one officer asked, glancing down at a list of names. Agwa nodded, unknowingly walking into their trap.

Agwa spent the next three months in a tiny jail cell before being moved to a larger prison — a long, narrow warehouse packed with criminals and other suspected rebels. The place reeked of urine and sweat, and Agwa’s new bed was the ground next to the one large pot that served as the prison’s toilet — a vat that would get so full that urine would splash on Agwa as he was sleeping.

Each day, Agwa and the other suspected rebels had to empty the pot, carrying it on their shoulders through the crowd, shit and piss splashing down their bare backs.

Twice a day, the prisoners shuffled outside in shifts to cook their own food over an open fire. Machine-gun-wielding guards would lead the men to a large, flea-infested pile of waste, where they could squat in a circle to defecate. Starving prisoners would sometimes scavenge food from that very pile, picking moldy plants that sprouted.

For a year, Agwa lived like this, surviving disease and criminals and prison uprisings. Then he felt his last hopes drop when the guards told him that a Communist leader would be there later in the day. Agwa was certain the man was coming to shoot them all. He would die in filth.

But when the leader arrived, he posed one question to the suspected rebels: Did they want to die in this prison, or die at war?

Agwa did what he had to do to survive: He lied. He said he’d fight.

He was briefly released from prison, allowed to go to Gambela to see his family before going to war. Instead, Agwa quickly set off on foot through the jungle, heading to Sudan — a haven for Ethiopian refugees at that time.

Agwa had no weapons, no food, no water. He wore a thin T-shirt, jeans and old, gray Converse All-Stars. In his pocket he carried a tiny bag of gold dust — something he could exchange in Sudan for refuge if he needed to.

He had no compass, but looked high up to the tops of the towering jungle trees for signs of moss. Moss meant shade. Moss pointed north. That and the sun would guide him to Sudan.

VI

In Sudan, he again slept on the streets as he had done as a teenager. As Ethiopia’s violent conflicts showed no signs of slowing, Agwa obtained his legal refugee paperwork, and soon heard that American social workers were offering refuge for Ethiopians in the United States.

He’d also soon hear from other Ethiopian refugees that the girl he once knew — that smart girl Ariet Oman from the Gambela classroom — was set to arrive in Sudan any day. She, too, had been recruited to the warfront, refused to conform and like Agwa paid for her dissent, in a women’s prison. When she was released, she fled the havoc of Ethiopia.

When Agwa’s chance came to file paperwork to emigrate to America, he wrote a name under “spouse” — the name of a woman he once would have never dreamed of marrying: Ariet Oman. When she arrived in Sudan, Agwa told his old high school friend of his plan. If they married, they could go to America together. They could escape. They could support each other, watch out for each other.

Agwa and Ariet didn’t have a wedding — just a simple justice-of-the-peace ceremony.

Americans wouldn’t understand their marriage, Agwa says now. He loved Ariet, but theirs was never a romance. It was a love grounded in a place — the village where they’d felt the same hard dirt under their bare feet, the place where they swam in the same warm river as children.

That day, they pledged that they would always be there for one another, no matter what befell them.

With each other — wherever they went, as far away from Ethiopia as they flew — they could always be Anuak.

VII

On a blue-sky afternoon after his regular Sunday church service, Agwa sits in the living room of the tiny South Hill cottage he shares with his youngest daughter. The room’s yellowing white walls are sparse: paintings of flowers and lions, a depiction of The Last Supper. Bookshelves are lined with stacks of National Geographic magazines.

When Agwa talks about those first days he and Ariet lived in Spokane, he sometimes is in hysterics, laughing at everything they had to learn. Life sped up.

Garbage disposals. Dishwashers. Answering machines.

Birthdays. Agwa had to make one up — Nov. 15, 1963.

Ariet liked America. She realized that they would never want the way they did in Africa. She used credit cards. She drank beer. She loved pizza.

Agwa marveled at the enormous supermarkets, with gleaming vegetables and cartons upon cartons of beautiful eggs. He cooked an egg at home. It tasted like nothing.

Agwa wanted to be nothing but Anuak. And he saw that Ariet wanted to stay Anuak, but to feel American. The tension began.

Two baby girls came along. First, Gilo. Two years later, Abang.

Ten years after they arrived in the United States, Ariet and Agwa couldn’t agree on anything. They hurt each other. They fought. They separated. They came back together. They divorced.

Their vicious, public ire for each other made their American friends uneasy. But behind it all, Agwa and Ariet clung to each other.

When Ariet got a job taking calls for a local bank, she turned to Agwa. Across town, he called her, pretending to be different angry customers so she could practice.

* * *

On Gilo’s 13th birthday — Dec. 13, 2003 — soldiers and highlander militias destroyed Gambela. They used automatic weapons and grenades, machetes, axes and clubs. They killed 424 Anuaks. They dragged the bodies into the streets and ran over them with trucks, according to a Genocide Watch report.

Schools were invaded. Soldiers put guns to the heads of girls and told them that their race would be raped into extinction.

When it all happened, Agwa was at an all-you-can-eat pizza joint in Spokane. He watched his daughter blow out candles on a store-bought cake. A friend called: He told Agwa his people had been murdered.

Agwa wondered: Was this a sign? He had survived so much, and was God now calling him to save his people?

Agwa launched a local campaign to build an orphanage in Gambela for kids whose parents had been killed. Abang, his 10-year-old daughter, filled an oversized pickle jar with $625 from her elementary school classmates.

But Americans were skeptical of Agwa’s efforts. They wanted more information. More time. More money. More planning. Agwa made demands. His passion was interpreted as rage.

In 2007, he boarded a plane for Ethiopia alone. Under the hard sun, survivors of the genocide looked as if they’d been working for hundreds of years. They told Agwa he looked like he was born yesterday.

Agwa wasn’t a part of them anymore.

* * *

Decades before, when he fled from Africa with the strongest woman he’d ever met, Agwa never would have predicted that one day she would wither, too.

By 2012, Ariet had become a shut-in, wrecked by the bottle. She fell and hit her head. Doctors repaired her brain. They called it a miracle.

But her liver and intestines were shot. She bounced from nursing home to hospital. With Agwa at her bedside, Ariet asked if he could forgive her. The squabbles. The court fights, the gossip, the pain.

“Ariet, I forgave you years ago,” he said.

He told her he had dreams of her future: She was old and in a wheelchair, grandchildren playing at her feet. He told her to hang on.

In a room last October at Sacred Heart Hospital, Agwa sat by his old friend. In her final moments, as their eyes connected, Agwa could see her fear.

In her eyes, he also saw that smart girl from the Gambela schoolhouse. He saw everything they’d been through together — the pain that they’d caused each other, the things they’d survived. He saw her pleading in his eyes, begging him to stay by her side, just like they’d promised each other in Sudan.

VIII

On recent a Saturday afternoon at a Hillyard warehouse, Agwa — now in his late 40s — loads a five-foot-tall stack of thin cardboard sheets into a large printing machine. On the other side it spurts out packaging: brightly colored applesauce and beer boxes, and tiny packages for bullets. He works the graveyard shift — 3 am to 1 pm. Sometimes he’ll work through the weekend.

As he walks around the warehouse floor on a break during his shift, he can’t say whether this is what he thought his life would become when he dodged slavery, homelessness, prison and war.

He says he feels like a man suspended in a void between his broken homeland and the place he’s rested his head for the past 27 years — like a man without a country.

He still listens to BBC Radio to hear snippets of news from Africa. He tries to remember what it was like back home. The way the warm water of the Baro River embraced his body as a boy. The chatter of the village on market day.

On some nights in Spokane, he spreads a bedsheet on the floor of his living room. It reminds him of the animal skin he had as a child, and he can feel the hard ground underneath him as he sleeps.

For a moment he’s home again.