"The strongest reason for the people to retain the right to keep and bear arms is, as a last resort, to protect themselves against tyranny in government."

Except Jefferson never said that.

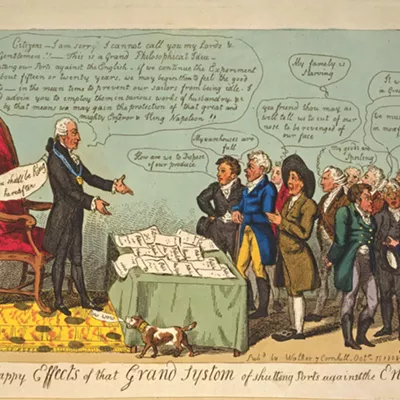

Politicians, pundits and angry uncles all enjoy sharing quotes from the Founders. But they often don't particularly care if Jefferson, Madison or others actually wrote what they claim they did. Invoking the words of key figures from the Founding period is a rhetorical strategy that aims to mobilize the intellectual giants of American history to support modern-day political positions.

It is the very opposite of what history should be. Serious scholars begin with questions and then seek answers in historical sources. Politicians (both the professional and the amateur variety) do the opposite. They begin with answers — their preferred political positions on an issue of the present-day — and then seek out a short, pithy quote from the Internet to help bolster their argument.

The Internet, I think we've all learned over the past few years, is not the most reliable source. Cyberspace is awash with bogus quotations from the Founders and other key historical figures, like Abraham Lincoln. You can easily shop around to find Washington or Theodore Roosevelt espousing a 21st century political cause that would have been completely unimaginable to them in their own time; Alexander Hamilton did not go on the record about his views on cryptocurrency. The danger to our political discourse, though, is that many of these fraudulent quotes are all too easy to believe when you're looking to confirm what you've already decided.

How do we guard against the spread of historical misinformation? First, be suspicious. If a politician invokes an authority from the past, be skeptical. Second, do some homework. There are bona fide resources that are easily accessible online that track false quotations. A librarian at Thomas Jefferson's Monticello, for example, has maintained a website of "spurious quotations" attributed to Jefferson for well over a decade. The false quote above, for example, first appeared in print in 1989 and took on a life of its own in the 1990s. (You can read the entry about it here: monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/strongest-reason-people-retain-right-keep-and-bear-arms-spurious.)

Why do we care so much about what the Founders said over two centuries ago? Hot button political issues are usually wrapped up in questions about the meaning of the Constitution. One legal philosophy in constitutional law is the concept of "original intent" — what did the Founders mean when they wrote the Constitution? Original intent draws a straight line from the founding period to the present in ways that invest the Founders' words with significant power to shape the future.

Cherry-picking quotes to work out the original intent of the Founders is a different kind of historical misinformation. One of the potential pitfalls of original intent is that it can view ideas as timeless and unchanging. Historians, however, are all about context. We see ideas as the product of their time and place. While there is both continuity and change over time, historians tend to agree with the writer L.P. Hartley who wrote (honest!), "the past is a foreign country; they do things differently there."

It is important to understand quotes in their historical context. For example, a quote from Washington in 1754 is likely to be different to one from 1789. In 1754, Washington was in his 20s, fighting in the Seven Years War as a loyal subject of King George III. In 1789, he was 57, a global celebrity, and the first president of the United States. So, the question is, which Washington should we listen to in 2022? The one from 1754, or the one from 1789? Sadly, the answer, all too often, is the one who agrees with us.

It is important to understand quotes in their historical context. For example, a quote from Washington in 1754 is likely to be different to one from 1789.

Quotes, then, offer a very narrow window on the past. So what can we do to try to understand the views of the Founders? Do some research in primary sources. While the Internet has created serious problems for finding reliable information, it has also provided unprecedented access to verified historical documents. You can access the papers of Washington, Jefferson and others for free through the Library of Congress website. The National Archives "Founders Online" does the same for over 185,000 documents from figures like Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison.

That is a lot of reading. So the second-best thing to do is to read the work of historians, who have dedicated decades of their professional lives poring over these documents. Bona fide historical writing goes through a rigorous blind, peer-review process to ensure that scholars adhere to ethical and professional standards in their use of evidence, but it is always a good idea to be a critical reader. While quotes represent a moment, frozen in time, the best historical studies offer a broader picture of the past that helps to explain how and why the Founders' differed in their interpretations of the Constitution and, importantly, why these ideas changed over time.

Last, never trust a politician quoting Jefferson. ♦

Lawrence B.A. Hatter is an award-winning author and associate professor of early American history at Washington State University. These views are his own and do not reflect those of WSU.