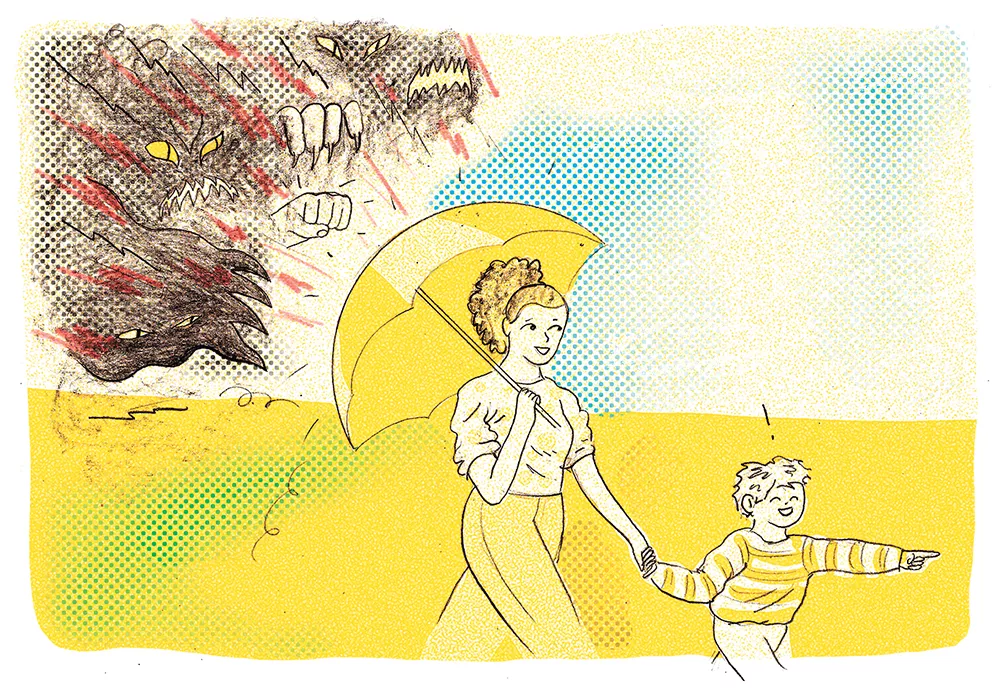

I'll admit it. I avoided reading the Spokane Regional Health District's "Confronting Violence" report for months. The last thing I expected to find in its pages was a compelling message of hope regarding our ability to end violence together. The more we learn, the more we see that the tools to eliminate violence are already in our hands. To start, we need to face the dynamics of the problem head-on, while learning from and committing to the power of the solutions that are already around us.

Violence is a clear health equity issue in Spokane County. Frequently, race or economic standing is disproportionately associated with various violence and health factors. Two harrowing examples are that black teens are six times more likely to be homeless than their white peers and that there is nearly a 90-fold difference in violent crime between Riverside, the highest violent crime, highest poverty neighborhood, and Five Mile, the second-lowest violent crime and lowest poverty neighborhood.

In reading about the different forms of violence in Spokane County, you'll notice a blurring of the line between victims and perpetrators. Statistically, being one makes you more likely to become the other, and many risk and protective factors are predictive for both. Perpetrators are often victims of forces beyond their control, and accountability measures that fail to see this can actually perpetuate the cycle of violence, instead of breaking it. For example, research shows that incarceration fails to serve any rehabilitative purpose and children with parents in jail are more likely to commit violence themselves later in life.

The report pulls apart the four levels on which violence factors operate. This "socioecological model" shows why comprehensive approaches are better than narrowly focused ones. By understanding the ways that "systems of violence" combine and operate, we can build counter-systems of resilience, such as stronger neighborhoods where people are available and willing to help each other out.

My cousin Luke stopped violence in its tracks with the help of family, some professionals and publicly funded social supports. As a high-functioning autistic student who experienced bullying in school, multiple risk factors culminated in fights and a chair being thrown through a window. The situation was compounded by expulsion and being sent to a program for kids with criminal records. Fortunately, a social worker recognized that Map High School would be a better fit, and from there Luke was able to connect with a series of resources that helped him secure employment and learn to live free of violence.

Half the battle is believing that change is possible. Fortunately, the data show that our circumstances aren't inevitable. The numbers of Spokane County teens reporting being in fights, wanting to harm someone, or being arrested has actually gone down over the past 10 years. Too often we focus on shocking stories, rather than understanding the power of prevention in effective strategies and programs.

So don't turn away in defeat and allow violence to spread. Let's stand together and create the conditions for the safety and prosperity we all want and deserve. ♦

Mariah McKay is a fourth-generation daughter of Spokane and a community organizer campaigning for racial, social and economic justice. She has worked in biotech and government and currently serves as a public health advocate.