On Aug. 12, FBI agents executed a search warrant to hunt for missing top secret government documents in former President Donald J. Trump's Mar-a-Lago resort and home in Florida. The unsealed warrant revealed that a federal judge determined that the FBI had probable cause to initiate a search of Trump's property as part of a criminal investigation into the mishandling of government documents, which includes possible violations of the Espionage Act of 1917. The search revealed 11 sets of secret documents that allegedly touched on highly sensitive subjects from nuclear weapons to the president of France. Trump, however, claims that the investigation is politically motivated.

While an FBI raid of a former president breaks new ground in U.S. political history, Trump is certainly not the first member of the executive branch to stand accused of posing a risk to national security. Edmund Randolph, who served as the second U.S. secretary of state in President George Washington's cabinet, resigned in disgrace in 1795 when he was accused of sharing Cabinet secrets with the French.

The two cases are not the same. The FBI is not investigating Trump for deliberately handing over documents to a foreign power; Randolph was not prosecuted for his malpractice. But the political responses to these two scandals point to strikingly different cultures of accountability in 1795 and 2022. Trump has made political capital out of the FBI investigation by raising funds from his supporters in preparation for running for president again in 2024. Randolph's misbehavior, by contrast, killed his political career and ensured that he is a largely forgotten figure among the Founders.

Trump and Randolph couldn't be more different. Randolph was a member of one of the oldest and most powerful planter families of Virginia. Trump is a nouveau riche New Yorker. Trump ran for president as an outsider; Randolph was governor of Virginia, a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, and the first U.S. attorney general. When Thomas Jefferson stepped down from George Washington's Cabinet in January 1794, the president appointed Randolph to replace him as secretary of state.

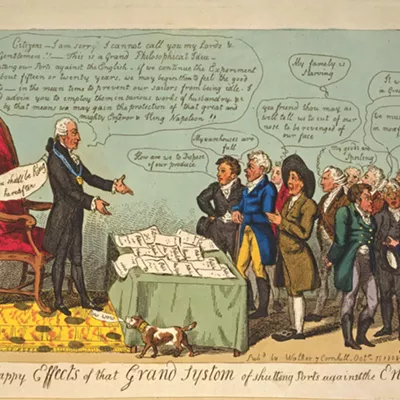

Randolph joined the State Department at a moment of global crisis and bitter domestic partisanship. The outbreak of the French Revolutionary War divided the globe between supporters and opponents of the French Republic. This divide put the United States in a bind. Should it support a sister republic and old ally, France? Or should it try to stay out of European affairs. This question polarized American politics in the 1790s. The nascent Democratic Republican party favored France, while the fledgling Federal party supported Great Britain — France's inveterate enemy. Washington's support of neutrality aligned him more closely with the Federalist members of his Cabinet, while Randolph was a Francophile Democratic Republican.

Popular protests rocked American cities in 1795 in response to the Jay Treaty. The agreement, negotiated between John Jay and the British government the previous year, hoped to avoid war between the two countries. But Democratic Republicans saw the deal as pro-British and a betrayal of America's French allies. As the Senate prepared to ratify the agreement, Jay quipped that he could walk the length of the United States from New England to Georgia by the light of his burning effigy. Shocked by the vocal opposition to ratifying the treaty, Washington decided to cut short his summer at Mount Vernon to consult his Cabinet in person to plot a path forward in August 1795.

Washington could not have imagined what he would find on his return to Philadelphia. Secretary of War Timothy Pickering, a Federalist, informed the president that Edmund Randolph was a "traitor." Pickering had laid his hands on a dispatch to Paris from a French diplomat in Philadelphia. While the note was incomplete, it was clear to the reader that Randolph had, at the very least, relayed confidential policy disagreements within the Washington administration to a foreign power. This revelation encouraged Washington to abandon Randolph's advice and forge ahead with ratifying the Jay Treaty. Moreover, he confronted his errant secretary of state with the dispatch in front of the whole Cabinet. The stammering Randolph began by claiming that he could not remember the particulars of his meetings with the French diplomat. He ended the meeting by resigning in disgrace.

Randolph was never charged with any crime, but his political career was over. His actions, most likely naïve indiscretions, had nonetheless violated the accepted norms of political behavior in the founding era. Historian Joanne Freeman has explained how early U.S. politicians, most of whom met in Philadelphia as strangers from the different states, embraced an honor culture that provided strict boundaries of political behavior to create the trust necessary for the fledging government to function. Limiting partisanship was essential to the survival of the republic. Even in 1795, at the height of partisan struggles from Congress to the city streets, Randolph discovered that there were limits to legitimate political action. Democratic Republicans did not reflexively leap to his defense with "whataboutisms" or cries of partisan witch hunts.

Thinking about the political fate of Edmund Randolph should lead us to reflect on the failings of our own political culture. In this age of hyperpartisanship, are there certain acts that ought to disqualify someone from public office? Could Trump really shoot someone on New York's Fifth Avenue and still be a force in U.S. politics? Has he erased all of our political norms so that there are no longer any limits to the ruthless pursuit of power in 21st century America? The GOP's response to the FBI investigation might suggest that he has, but the ultimate decision is up to the voters. It is our job to hold our leaders accountable when political norms prove unable to do so. ♦

Lawrence B.A. Hatter is an award-winning author and associate professor of early American history at Washington State University. These views are his own and do not reflect those of WSU.