In a state that likes to think of itself as committed to social justice, how we funded schools before 2017-18 gave kids in school districts with high property values access to an education that kids in districts with low property values often didn't get. Not only is that shameful, but in a 2012 decision called McCleary, the state supreme court found it unconstitutional. New funding was provided, but simply spending more money hasn't solved the problem.

The court warned us it wouldn't.

In the McCleary case, the court ruled that our state constitution requires the state to pay for all basic education costs, and found that too many school districts were instead covering basic education costs using local levy dollars to do that.

That meant in high-property-value school districts, where people were OK paying more taxes, kids received not only basic education including continuing and technical education, bilingual services, and special education, but also sports, drama, special academic programs, field trips and events. Some property-value-poor districts struggled to pass levies and to fund the basics, while some of those districts that did pass levies still could not raise enough money to cover basic education costs.

The court ordered the Legislature and governor to begin passing budgets that amply funded basic education for every child regardless of where they grow up.

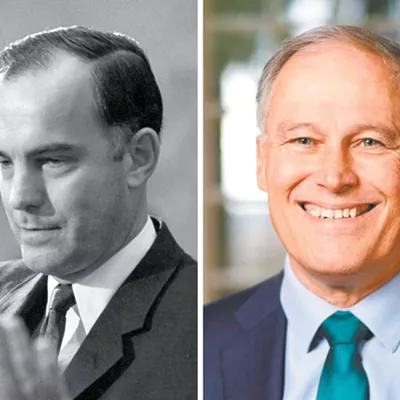

In 2017-18, the state spent billions of new dollars on education. Gov. Jay Inslee celebrated, saying "at long last, our Legislature is providing the funding necessary to cover the basic costs of our K-12 schools." But barely five years later, districts are once again needing local levies to fund basic education.

Central Valley, for example, spends $4.5 million and Cheney about $1.7 million of their own money on special education, which should be fully funded by the state. Local districts use levy funds to pay for transportation, food service and transitional bilingual instructional programs.

How did we spend billions more on education, then end up in nearly the same spot?

The new billions the Legislature appropriated were expected to fill shortfalls in transportation budgets, fully fund special education, fund reduced K-3 class sizes, fund remediation services for struggling students and bilingual teaching, and bring some salaries up to a market rate. School levies were to be used for programs not covered by the state's definition of basic education.

But the state agreed the new money could also be spent on raises, and once that happened, teachers' unions demanded it. I have absolutely zero problem paying teachers well, and the unions were just doing their job. Additionally, the contracts resulted from collective bargaining.

So what's the problem? Well, we should understand in these salary negotiations that school superintendents and largely volunteer school boards sit across the table from negotiators who are fully aware that if they drag out talks until August, the school board will be under pressure to open classes on time. In the summer when the new money flowed in, strikes, timed to coincide with the start of the new school year, were authorized and discussed across the state, including districts in and around Spokane.

To avoid strikes, some districts on the West Side agreed to raises of more than 15 percent. As the new state funds flowed in, the Mead School District agreed to a new contract in 2018 with a 15 percent increase. The bar was set.

In the end, the teachers' union boasted its "members in school districts across the state negotiated historic pay increases."

The problem is, after the "historic pay increases," money that was to have amply funded all basic education programs and salaries overwhelmingly went to salaries.

But simply blaming the current situation on pay raises is too simplistic. The court had warned that "Pouring more money into an outmoded system will not succeed." It cautioned "...fundamental reforms are needed for Washington to meet its constitutional obligation to its students." But fundamental reform is hard, spending more money is easier, and that is what the Legislature did.

The Legislature can claim it sent sufficient money and if the districts didn't spend it as the state model suggests, that is not on the Legislature. There is a point to be made there, but the state distributes funds based on student and school needs calculated from 1970-2010. Districts trying to meet the needs of 21st century students must rely on local levy dollars.

By the end of September, a committee is supposed to advise on how to fix this. It's recommendations need to be blunt and bold. Voters in November need to elect legislators who have the spine and spleen needed to ensure that state funds are spent providing a basic education to all children.

Here's three simple but politically tough recommendations that would go a long way toward achieving a more equitable funding system.

The state should provide each district with the same, fixed amount of dollars per student. That amount must be considerably more than what's needed to sufficiently fund basic education.

Limited upward adjustments to the per student amount should be made for special education, and for areas with high remediation needs, and with high housing costs. However, the cost of housing adjustments should be based on large, metropolitan areas, not on a district-by-district basis.

The Legislature must cement the maximum amount per student that may be spent on basic education salaries, and restrict the use of local levy dollars to only funding programs and positions not covered by the state's definition of basic education.

In its McCleary decision, the court wrote that "...the legislature has an obligation to review the basic education program as the needs of students and the demands of society evolve." Reevaluating basic education to meet modern needs, and adjusting funding systems to ensure funds are spent where they are needed and ample enough to meet basic education costs will require considerable legislative effort. But that effort is the Legislature's paramount responsibility. Complying with McCleary may be a box many legislators think they've checked, but their work is not yet done. ♦

Bill Bryant, who served on the Seattle Port Commission from 2008-16, ran against Jay Inslee as the Republican nominee in the 2016 governor's race. He is chairman of the company BCI, is a founding board member of the Nisqually River Foundation, and was appointed by Gov. Chris Gregoire to serve on the Puget Sound Partnership's Eco-Systems Board. He lives in Winthrop, Washington.