Aaron Burr's pistol blasted into Alexander Hamilton's body, shattering ribs, perforating his liver and lodging into his spine. Bile in his abdominal cavity caused agonizing peritonitis. Opium was administered to relieve Hamilton's excruciating pain.

Washington State's recent $518 million settlement with opioid distributors and the federal government's paltry $3.5 billion criminal fine of Purdue Pharma for its culpability in 500,000 OxyContin deaths are reminders of an insidious scourge. With a $1.3 trillion economic gut punch, a record 107,000 overdose deaths in 2021 and 841,000 deaths since 1999 (along with nefarious profits for Big Pharma and illicit dealers), the opioid epidemic is a massive, far-reaching tragedy.

This epidemic has roots in past medicinal uses of opium to relieve pain and treat common maladies. The history of opium and its derivatives (morphine, heroin) and synthetic opiates (hydrocodone, oxycodone) reveal a pernicious circle of legal use, addiction, prohibition and criminalization, leading to new, legal drugs marketed as safer and less "habit-forming."

Homer extolled opium for "banishing painful memories." Ancient Romans venerated Morpheus consuming an opium-based wine inducing the god's gift of sleep and dreams. Queen Elizabeth I chewed opium gum. Queen Victoria took opium in her Earl Grey.

The British East India Company — the Sacklers of the 19th century — exchanged Indian opium for Chinese tea, addicting millions of Chinese. The original "hipsters" might have been Chinese who smoked opium reclining on a hip; in the 1950s it became a reference to jazz musicians and Beat writers who used heroin.

In the mid-19th century's Opium Wars, English "foreign devils" subjugated the Chinese. Chinese history is defined by this humiliation and China's subsequent fracturing by French, German, Japanese and American imperialists. Perhaps there is a dark avenging reciprocity as the fentanyl that inundates our streets is manufactured with ingredients made in China.

Queen Elizabeth I chewed opium gum. Queen Victoria took opium in her Earl Grey.

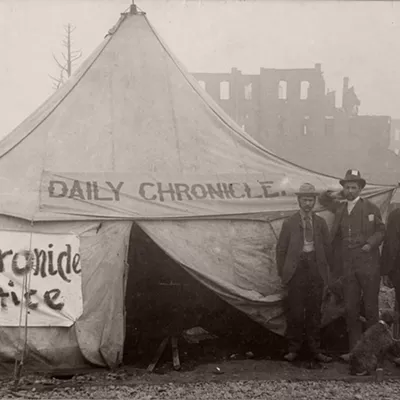

The Civil War Union issued 10 million opium pills to soldiers. Injured veterans were requisitioned unlimited supplies of opium and hypodermic needles, introduced in 1856. In 1888, opiates constituted 15 percent of prescriptions written in Boston. And in the antebellum South, Whites had one of the highest opium addiction rates in the world.

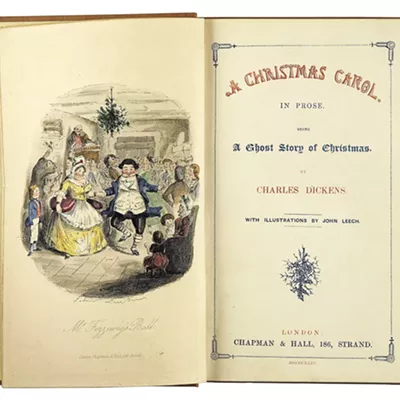

By the early 19th century, opium's addictive properties were well known, as illustrated in Thomas de Quincey's 1821 Confessions of an English Opium Eater. Legal and pervasive, vogue in artistic circles, opium inspired Mary Shelly's Frankenstein and Berlioz's hallucinogenic "Symphonie Fantastique." And recall the Wicked Witch's poppies that impeded Dorothy's passage to the Emerald City and the eccentric, morphine-addicted Mrs. Dubose in To Kill A Mockingbird. Today, Afghanistan supplies 75 percent of the world's opium.

In 1905, five years after the publication of The Wizard of Oz, Congress outlawed opium, by which time morphine (called "God's own medicine") and heroin, both more potent than opium, had become common household remedies. Following World War I, morphine addiction was called "soldier's disease." Nazi Hermann Goring was a morphine addict.

A chemist working for the German company Bayer in 1874 synthesized heroin, twice as powerful as morphine and 10 times stronger than opium. Heroin was marketed as a nonaddictive substitute for morphine and a cure for alcoholism.

Early 20th century heroin was used for many ailments. Dorothy's Aunt Em could go into any rural Kansas pharmacy and without a prescription acquire a heroin-based medicine. For the addict, nonmedicinal heroin offered a delusional escape from beige Kansas to kaleidoscopic Oz. In 1924, the U.S. government banned heroin.

When OxyContin was introduced in 1996, the medical mantra was "pain management." Purdue engaged in a marketing blitz, incentivizing reps who pushed the most pills with bonuses, one year totaling $100 million. Some physicians, pliant from rep gifts, made Faustian bargains with Purdue and overprescribed. The company claimed that only 1 percent of patients would be addicted. A CDC study suggests the real figure was 16 percent.

Initially OxyContin addiction was a "disease of despair," afflicting mostly working class, rural Whites. OxyContin was even called "Hillbilly Heroin." In one tiny, rusting West Virginia town, like the one eulogized in Iris Dement's lament "Our Town," Big Pharma dumped 9 million hydrocodone pills into its single pharmacy. In 2012, United States health care providers wrote 255 million opioid prescriptions, an average of 81.3 prescriptions per 100 persons.

Statistics show that physicians tended to more cautiously prescribe the drug to African Americans, perhaps believing that Blacks were more prone to addiction than Whites. Eventually OxyContin infested even affluent White communities, as prescription drugs are socially acceptable and less stigmatized than something bought on the street like heroin. White suburban addiction, overdose casualties and denial proliferated. For bourgeois America, OxyContin gentrification was like the hissing, rapacious insects under David Lynch's halcyon Lumberton manicured lawns in Blue Velvet.

In 2014, when OxyContin was belatedly changed to a more restrictive classification, heroin became the default drug. Then illicit OxyContin hit the streets, and dealers diluted the product to increase revenue. Then addicts needed more cash to buy more, more often resorting to crime to get it. Public policy prioritized criminal penalties not recovery. Consequently, 60 percent of the federal prison population was serving time for mostly nonviolent drug offenses.

If history is instructive the OxyContin epidemic will dissipate, but the cycle will repeat. Then a new favorite opioid, perhaps Soma, will be hustled as a safe pain panacea. For some Americans, the blue spark of the dopamine pleasure surge will be doggedly chased by the braying black hounds of addiction. ♦

John Hagney is a retired history teacher, spending 45 years at Lewis and Clark High School. He was named a U.S. Presidential Scholar Distinguished Teacher and published an oral history of Mikhail Gorbachev's reforms that has been translated into six languages.