As in 1864, when Chief Black Kettle led the skeletal remains of his bands of southern Cheyenne in the direction of Colorado’s Fort Lyon, and into Sand Creek, where he flew an American flag and a white flag above his tent and was still cut down by a killing squad of 700 men.

And at the frontiers, too, in 1845, when the explorer Sir John Franklin set sail from England with two refitted bomb ships — bearing the dread-laden names HMS Erebus and HMS Terror — to search for the Northwest Passage. Franklin’s expedition was seen by two whaling ships, sailing into waters no one had sailed before, and then never seen again.

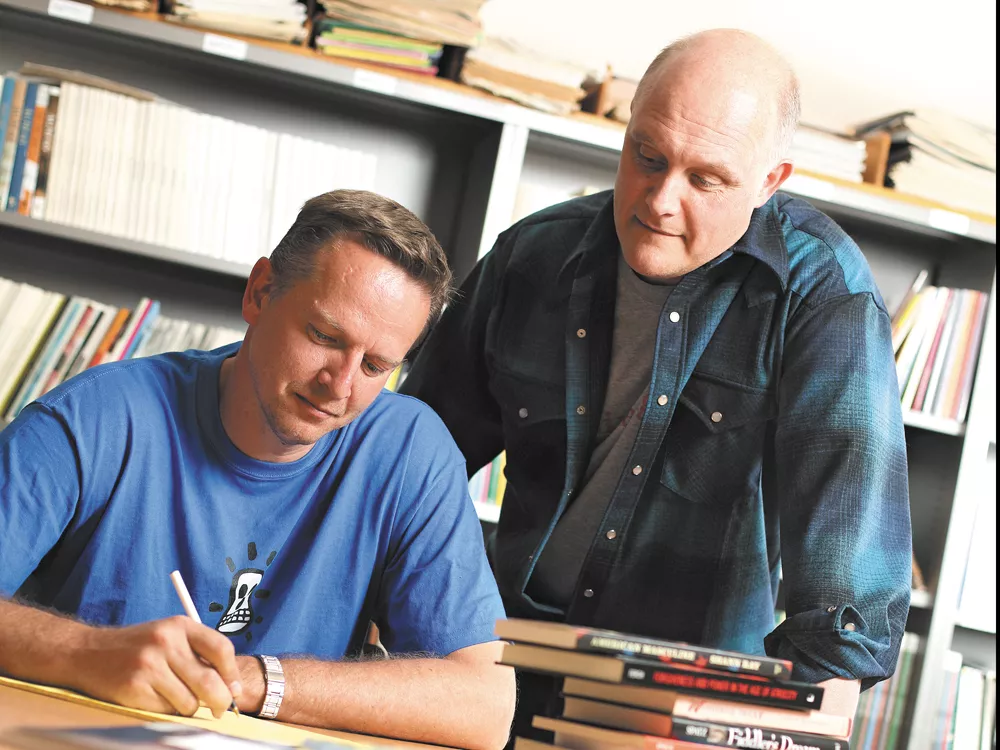

Local authors Greg Spatz and Shann Ferch (he writes under Shann Ray) say it is also at these frontiers that history, the naked circumstances that befall great men and women, has an opportunity to become literature — a force for drawing, from specific lives, a portrait of our universal humanity.

Spatz’ Inukshuk, already on bookstore shelves, follows a father who watches his son become more isolated and increasingly obsessed with making a film about John Franklin’s disaster. Ray’s Blood, Fire, Vapor, Smoke — a novel in progress — uses the Sandcreek Massacre, along with period correspondence of white copper barons and freed slaves to imagine the lives of three people — one Native American, one white and wealthy, the other white and poor — on the frontier at the turn of the 20th century.

For their toil, Spatz and Ray were both awarded fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts this year — one of the most prestigious grants in literature. More than 1,100 people applied and only 37 fellowships were granted. It’s rare for a town Spokane’s size to land two winners in a single grant cycle, says the NEA’s Victoria Hutton. Seattle and Portland, for example, had none.

But Spatz, 48, and Ray, 44, are even closer than that. When Ray was a creative writing student at EWU, Spatz was his thesis advisor.

It’s late June. Greg Spatz and Shann Ray settle into club chairs in the expansive lobby of Gonzaga’s Tilford Center, and they work their way into the hesitant rapport of people who have shared intimate moments, but aren’t close.

Spatz mentions how much nicer Ray’s accommodations are here (Ray teaches in GU’s leadership studies department), than EWU’s creative writing offices. Ray talks about the great light that comes in from the large old warehouse windows of this remodeled paint factory. Spatz says he works out of a cubicle in EWU’s Riverpoint Campus and has to take meetings with his advisees in a conference room. The men laugh about this.

Talk turns to Ray’s application to Eastern’s creative writing program. They go back and forth about the date. 1999? 2000? Either way, Spatz says, it wasn’t good. Ray smiles a pained smile and agrees. Spatz says Ray was the last person to be admitted to the program that year, and even then, it wasn’t because of the quality of the writing. The faculty thought that, maybe, since he lived in Spokane, Ray could come on short notice.

“He was a real question mark,” Spatz says.

Ray snorts. “I was a question mark to myself,” he says.

Both men say they began writing fiction alone. After college, Spatz paid the rent as a professional musician who wrote when he wasn’t playing fiddle. Spatz says he wrote a lot, but felt like the work was leading to dead ends. “I couldn’t get any perspective on my own work,” he says. “I was getting more and more stuck.”

He got a masters in creative writing at the University of New Hampshire and then an MFA from the prestigious Iowa Writers Workshop, after his friends told him that a masters alone wouldn’t cut it. He landed his professorship at EWU in 1998.

Ray was born to a working-class Montana family. He says his parents “cherished education, but in the utilitarian way of wanting to have more opportunity.” Ray didn’t think about pursuing writing in school because he hadn’t yet learned to love reading. He began writing and had a mind to explore the morality of human life, our kindness and our brutality. His first work, though, showed “too much rigidity, too much linearity,” he says.

Ray was in his early 30s — a doctor of psychology, teaching at GU and handling a full client load, writing fiction and poetry late into the night. He began wondering if there were ways to learn the craft of fiction.

“I’d read 30 books on writing, but I wasn’t just getting to what I hoped for. I knew I needed some sort of apprenticeship,” he says, but he didn’t even know things like MFA programs existed.

What Ray found at Eastern was a place to write and discuss writing and to understand what it meant for him to be a writer. “For me it was the conversations about voice and style,” he says, learning as much from authors they studied as in contrasting his personal voice with that of his classmates. “I think it took me a while to settle into, ‘Yeah, this is my style, and it’s not those other 10 styles,’” he says.

Spatz says he believes finding one’s voice and solidifying one’s perspective is the point of a writing program. Equally important is the opposite: “understanding audience, understanding who [a story] is directed to and how an audience will respond,” Spatz says. “It teaches you, ‘How do people read? How do you communicate with them?’”

And when we know how to communicate, what do we say?

Spatz and Ray are very different writers. They’ve spent the last few years looking at different dark and bright parts of the human soul. Both men say they’ve found in our history clues to our present.

When Franklin went into the wild, he carried 1,000 books with him, Spatz says, “his entire civilization.” The impulse that leads us into Canada’s tar sands and into wars abroad, Spatz says, “is the same impulse that led [Franklin] to look for the Northwest Passage — the same notion of conquest. The desire, not to understand, but dominate.”

Ray saw similarities, too, in the way different oppressed groups spoke about their oppression. “What was being said by Native Americans — especially the peace chiefs — was very similar to what I read in Frederick Douglass’ letter to his slave owner,” Ray says.

We are explorers, after a fashion, carrying our civilization with us as we go. And we are butchers of a sort, too. The impulses that drove men to massacre still drive them to control and degrade and subjugate.

But Spatz and Ray also believe, in their ways, that the common thread of humanity that keeps us making the same mistakes, is the thing that keeps us seeking reconciliation with one another and the thing that, through centuries, keeps us recognizably ourselves.

“Whatever morality we have [in writing] is the morality we have earned in our lives,” Ray says. “That was one thing the [MFA] program taught me — your writing shows whatever you have.”