Though we might not always want to admit it, journalists don’t have superpowers. Being a reporter doesn’t give you more access to information than anyone else. Requesting public records, talking to business owners, or diving into archives — these are all things that everyone can do. It’s just that journalists make it our job to gather information. We dedicate our time to it because other people are usually too busy to sit through hours of meetings or sift through stacks of documents.

But I think it’s also our job to share the skills we learn so anyone can do their own research, if they want. The more we can share our experience, the more the whole community is empowered to learn new things. Information is power, and you can go find it, too.

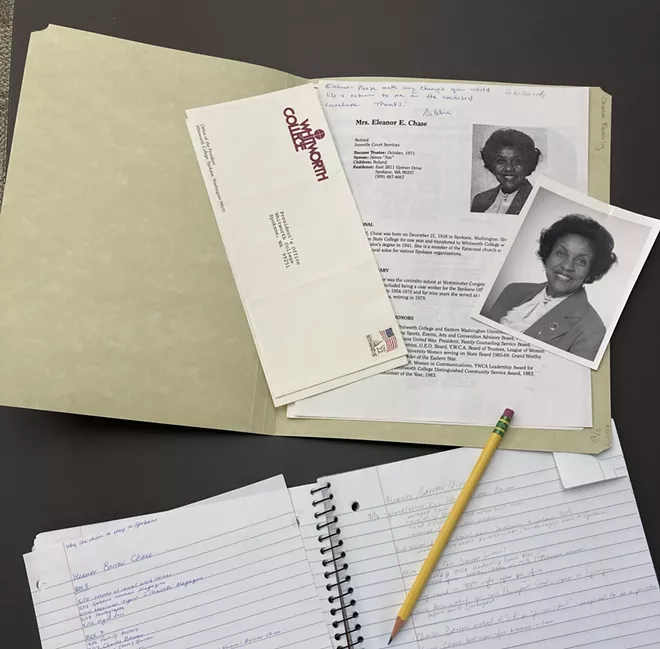

I just finished a story on the life of Eleanor Barrow Chase. Most of the research I did was in Eleanor’s collection at the Joel E. Ferris Archives at Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture, but I also found some great information in the Inland Northwest Special Collections at the downtown Spokane Public Library.

Both archives are available to the public, with archivists who are passionate about preserving and sharing knowledge. But if you’re not a trained researcher, you may not be familiar with how or where to start your own project.

Here are some tips on how to do your own archival deep dive to uncover stories on your own. It doesn’t take superpowers, but it’s always helpful to know what to expect.

1. Talk to the archivist. I promise you, the archivist is the most valuable resource in the entire collection by far. They have the most in-depth knowledge of the archive, and it’s their job (and joy!) to share it. If they want to, they might suggest files or folders that you wouldn’t have thought to ask for. So please, make their life easy. Follow the rules of the archive. Be punctual to your appointment. Show them that you’re grateful for their work. You might be there to research the past, but remember how important the people right in front of you are.

2. Learn what to ask for. Archives are generally organized like this:

Archive ⇾ Collection ⇾ Box ⇾ Folder ⇾ Primary Document

For example:

Joel E. Ferris Archive ⇾ Chase, Eleanor ⇾ Box 5 ⇾ Folder 17 ⇾ photograph of Eleanor and her parents

The whole trick of using archives is eventually finding the primary documents that will answer a question. Archivists can help at any stage of the research process, but you need to make it clear what kind of help you need.

If you’re starting from square one and don’t know what a particular archive has, ask for a small tour of their resources. You might discover that the archive has a special niche, or you might be able to skim a guide to see what’s in the archive. Sometimes resource guides are digitized, sometimes not. If you’re having trouble just finding a list of collections, ask the archivist. The list exists somewhere.

Need help choosing a collection to peruse? It may help to come up with a question or topic that’s broad but specific, and ask the archivist if they have any suggestions. I first learned of Eleanor Chase by emailing an archivist at the MAC to ask if she knew of any lesser known important female figures in Spokane. I had no idea that the MAC actually specializes in regional women’s history. (It’s embarrassing to admit how much serendipity affects my work.) The archivist invited me to come to the archive to chat about a few possibilities. She had great recommendations, and I could have written about any of the women she suggested. You don’t always hit the nail on the head that quickly, but it’s amazing what an email and a conversation can do.

Okay, let’s say you’ve narrowed down your research to one collection. Next, ask for the finding aid. This is often digitized, but not always. A finding aid lists the boxes that are in the collection, how many folders are in each box, and a summary of what each folder contains. This is where the rubber hits the road. You’re going to need to choose which boxes you want to look at. You’ll probably need to narrow your research question in order to choose the boxes that you think will be most relevant. Choosing the best boxes takes some prep and a little luck. When in doubt, ask the archivist for suggestions. But it’s up to you now to put on your detective hat and decide where to look for clues.

3. Make an appointment. When you’re finally ready to start your research, make an appointment. (This is true for most archives, but if you’re headed to the INSC at the library, no need! Walk-ins are allowed anytime during INSC hours.) In your appointment request, specify which boxes you would like to see. The archivist will pull those boxes and have them waiting for you when you arrive, so be on time and definitely don’t ditch.

4. Overestimate how much time you need. Archive appointments are usually up to four hours long, with good reason. It takes most people over an hour to go through an entire box, and I personally wouldn’t recommend trying to go through more than two boxes in one sitting. Also, you’re bound to get sidetracked by something interesting but ultimately irrelevant to your quest. Give yourself some margin for curiosity, but also learn to restrain yourself from endless rabbit holes you’re sure to discover.

5. Follow the rules. Like I said before, do everything to make your archivist’s life easier. Typical rules at archives are: No food or drink. Pencils and notebooks only, no pens. Keep everything you touch in order — that means looking at one folder at a time, one document at a time, and putting it back in the same place you found it so someone can find it again. Rules vary on laptops and phone cameras, so check with the archivist before you arrive. Typically, bags and backpacks will need to be left at the door.

6. Stay curious! Walking into an archive is like walking into any library — there is far more information around you than you’ll ever be able to learn. But let that be exciting and wonderful. The more time you spend asking questions and looking for answers, the less exhausting and more invigorating it can be. Archives are some of the best places to realize how much information and history are not online. So empower yourself with some new research skills and give us journalists some friendly competition.