The time was probably early summer of 1810 when a small group of strangers rode into the Spokane village on the flat point of land at the confluence of the Spokane and Little Spokane rivers. Summer salmon runs would have just begun, drawing families from many Plateau tribes to their traditional fishing camps. A wickerwork weir that jutted into the Spokane River diverted some of the salmon into eddies, where the men could spear them in great numbers; another weir stretched across the entire width of the Little Spokane. Women split the catch, then hung the red-fleshed halves on wooden racks to dry. The smell of salmon oil and the buzz of yellow jackets would have mixed with stick game songs in a variety of languages amid dust kicked up by ancient dances. The Spokanes called the confluence of the two rivers “the gathering place.”

No surviving account describes the arrival of these newcomers, but they had started from Lake Pend Oreille. Their leader, Jacques Raphael Finlay, was employed by the North West Company, a fur-trading conglomerate based in Montreal that was expanding into the Inland Northwest. Jaco and his small crew of French-Canadian voyageurs came bearing trade items such as tobacco, kettles, knives, wool cloth and fish hooks.

They were the first white men most members of the Spokane Tribe had ever seen.

In the 12 years they spent at the confluence — just north of the modern-day Nine Mile Dam — these men would mesh in important ways with local tribal culture, often wedding tribal woman. They had a hand in sending Spokane Garry — the middle Spokane chief who would spend his life trying to keep the peace between tribes and later settlers — off to Protestant boarding school. And though their presence was short-lived, compared with how long the Spokanes had been at Nin Chin Tseen — the Great Gathering Place — their impact is still felt today.

SIGNS

Long before Finlay arrived at their village, the Spokanes had felt the presence of Europeans. Spanish horses had reached the Plateau tribes at least half a century earlier; according to tribal tradition, the Spokanes traded their first animals from the Nez Perce. The horses thrived in the open pine prairies and nutritious bunchgrass, but even as Spokane families built up their herds, they would have known that the source of this new wealth could not be far behind. Tribal oral accounts tell of visiting Kootenais who escorted two French trappers into the area around 1800. The white men, whose balding heads and bushy beards sparked raucous laughter, were short of food, so the Spokanes fed them and gave them clothes. The men purchased furs and supposedly wintered in the Colville Valley before returning to the north.

A few years later, hearing of other white men to the south, the Spokanes dispatched two runners to the Snake River, where they met Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery and returned with a looking glass to show their families. After one more winter, stories filtered into the area of more fur traders in the Kootenai country. This was the party of North West Fur Company agent David Thompson, who crossed the Divide in 1807. During the next two years, Thompson built three trade houses in the drainages north of Spokane: Kootanae House at the source lakes of the Columbia; Kullyspel House on Lake Pend Oreille; and Saleesh House on the Clark Fork River.

In the fall of 1809, four Spokane men made an excursion to meet Thompson at a Kalispel encampment near modern Cusick on the Pend Oreille River, carrying gifts of a horse and several muskrat pelts. Thompson would have asked the Spokane emissaries about the geography and fur prospects of their homeland, and their answers must have convinced him to establish an outpost in their neighborhood,for in early May 1810, he gave his clerk Jaco Finlay “summer orders” that apparently involved the Spokane country.

JACO’S HOUSE

The son of a Scottish fur trader and a Cree mother, 42-year-old Jaco Finlay had worked most of his career in the Canadian Prairies as a clerk, interpreter and independent trapper. Beginning in 1806, he had scouted for the North West Company’s thrust across the Rocky Mountains. At the confluence of the two Spokane rivers, Finlay would have recognized that the variety of people and the trails converging from all directions created an ideal situation for a trade house. There was plentiful fish for food, horses to trade, bunchgrass for fodder and wood for building and firewood. Undoubtedly relying on tribal advice and approval, he chose a site and set his crew to building the first white settlement in present-day Washington.

Spokane elder Louie Wildshoe later recalled that his mother-in-law was a little girl when the first fur trade post was built at the confluence. She told him that the white people spoke French, and that they located their post halfway between the two rivers, near a long-established tribal village.

Jaco’s North West Company crew would have built many trade houses over the years, using one basic design: Three structures — men’s quarters, a warehouse and a store — were arranged in a U shape. According to Spokane tradition, the white men planted potatoes in their gardens; they also ate horse and dog meat. The whites traded with Spokane bands: flint and fire-starting steels; knives, axes and guns; pots and metal utensils; calico cloth and wool blankets. Soon, Jaco Finlay was living with a Spokane wife called Teshwintichina and had apparently settled in to a lifestyle that combined aspects of Plateau and fur trade culture. Their first child, a daughter later baptized as Marie Josephte, was born at the post.

At some point during the next year, Jaco was joined by another of David Thompson’s clerks, a strapping red-haired Scot named Finan McDonald.

Assigned to man the company’s Saleesh House on the Clark Fork River, Finan had joined a group of Flathead and Kalispel hunters bound for the buffalo country east of the Rockies in the summer of 1810. There he took part in a skirmish with territorial Blackfeet that resulted in several casualties. Fearful of reprisals, McDonald and his voyageurs rode west to Finlay’s new post. Thirty years old, full of both wild temper and good humor, McDonald traveled with a Kalispel wife he called Peggy and a young child.

Spokane House did not enter written history until chief agent David Thompson arrived there on June 14, 1811. He surveyed the pleasant flat of orange-barked ponderosa pine and made a brief entry in his field journal: “Thank Heaven for our good safe journey, here we found Jaco &c with ab[ou]t 40 Spokane families.” Since Thompson estimated seven or eight people in each family, his census indicated a village with about 300 inhabitants.

The next morning, Thompson produced his sextant and set about determining the latitude (47 47’ 4” N) and longitude (117 27’ 11” W) of the new post. After spending a day arranging the trade goods he had brought from eastern Canada (including two yards of wool cloth earmarked for Finlay) and trading for sucker fish and roots from the Spokanes, the surveyor headed north toward Kettle Falls to launch his historic run down the Columbia to the sea.

On the return trip the following spring, David Thompson made another brief stop at Spokane House. He feasted on fresh steelhead, then proceeded through the Colville Valley and up the Columbia. After crossing the Rockies and continuing on to Montreal, he used his meticulous observations to draw a series of large maps that detailed North America from Hudson Bay to the Pacific. These charts contained the first accurate depictions of the Spokane River, which he called the Skeetshoo, and the Little Spokane (Weir Brook). He also dotted in the network of tribal trails that led to the rivers’ confluence, where he carefully labeled “N.W Co. Spokane House.”

COMPETITION

For an entire year after Thompson’s departure, the North West Company enjoyed a monopoly on the fur trade at Spokane House and her subsidiary posts among Salish and Kootenai tribes. But competition was moving upstream in the guise of the Pacific Fur Company, founded by entrepreneur John Jacob Astor of New York City. The Americans had established Fort Astoria at the mouth of the Columbia and a post at the mouth of the Okanogan River in 1811. In August 1812, Astorian partner John Clarke led a party inland to compete directly with the Nor’Westers. Following a practice common among Canadian fur companies, Clarke chose a site in close proximity to Spokane House. By the onset of winter, the Astorians had constructed a four-room dwelling house for the “gentlemen,” a comfortable bunkhouse for the workers, and a capacious store for the furs and trading goods. Although the Nor’westers had always enjoyed amiable relations with the tribes who frequented the area, Clarke erected a pole stockade around his new post, with two corner bastions for defense.

Alfred Seton, a young American who was stationed at an outpost on the Clearwater River, arrived for a visit with the Spokane Astorians in October 1812. Hungry, cold and tired after an arduous trip, he wrote that Mr. Clarke “received me very kindly & treated me to the best his house afforded, which was but Horse.” Noting that the Astorians had already accumulated 15 packs (more than one-half ton) of beaver pelts during their short tenure, he observed that “the N. W. Co. did not much like the idea of our opposing them.” Another visiting clerk wrote of the “sly and underhanded dealings” between the posts, both parties making “the amplest protestations of friendship and kindness” all the while maneuvering to capture the most trade. To their credit, the managing partners of the competing companies agreed that they would not trade “spirituous liquors” to the tribes.

By late fall in 1812, Clarke’s “Spokan Fort” seemed on track for success. Then, sometime around Thanksgiving, the Nor’Westers’ fall supply run from eastern Canada arrived with the news that the United States had declared war on Great Britain the previous June, and that a British warship was en route for the Columbia. After a Pacific Fur Company messenger carried word downriver to Astoria, a cloud of uncertainty descended over the whole Astorian enterprise. The Americans realized that their small fort at the mouth of the Columbia would be defenseless in the face of the Royal Navy. After several rounds of negotiations, the Pacific Fur Company sold their inventory to the North West Company and prepared to return east, with the understanding that any of Astor’s employees who wished could transfer to the Canadian company.

In November 1813, the Nor’Westers moved their stock from their original house to the moreexpansive Spokan Fort. A young Irish clerk named Ross Cox found life at the Spokane headquarters quite agreeable. During the winter months, the river provided tasty sucker fish for sustenance, and spring steelhead were followed by rich runs of Chinook salmon; according to Cox, the residents “breakfasted on fish and dined on horse.” The traders planted a large garden of turnips, potatoes, cabbages, melons, and cucumbers. In the summer of 1814, bateaux ferried a rooster, three hens, three goats and three hogs upriver from Astoria. Someone captured a bear cub and housed it in the pig sty. There it was “fed daily by one of our Canadians, of whom he became very fond, and who in a short time taught him to dance, beg, and play many tricks, which delighted the Indians exceedingly.”

Summer at the post, Cox wrote, was occupied with “hunting, fishing, fowling, horse-racing and fruit-gathering; while reading, music, backgammon &c. formed the evening pleasures of our small but friendly mess.” Spokane House became known as a delightful place, a “centre of attraction” with handsome buildings and fine horses that the traders delighted in racing against Indian ponies on a nearby flat.

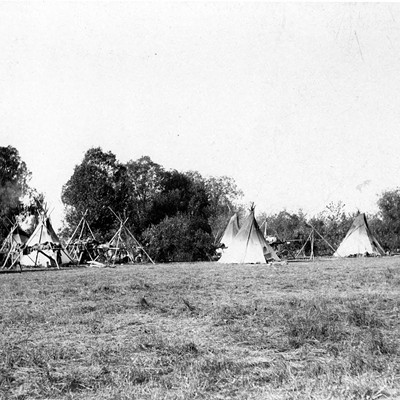

Ross Cox described meeting the headman of the Middle Spokane band, known to the whites as Ilum-spokanee, and visited their nearby village, noting that “some houses were oblong, others conical, and were covered with mats or skins, according to the wealth of the proprietor.” He learned of the ongoing barter for horses between the Spokanes and the Nez Perce Tribe while remarking that the Spokanes would never kill a horse for their own food, although they supplied animals for the fur traders’ table.

THE H. B. C.

In 1821, the North West Company merged with their primary rival, the Hudson’s Bay Company, headquartered in London. At first, little changed at Spokane House. A single surviving post journal, kept by Finan McDonald and another clerk from April 1822 to April 1823, provides a detailed look at everyday life at the post. A stream of different Plateau tribes visited from across the region. Relationships between these native people and the fur men were almost always amicable, and the gates to the stockade were only shut for a single night during that entire span. Many of the clerks and workers were married to Plateau women, who helped tend the gardens and prepare fish and hides.

The traders and the Spokane Tribe operated separate fishing weirs, and the tribal fishermen always seemed to catch more salmon, trout, steelhead and suckers in theirs. In one of the only tense moments recorded in the journal, a hot-tempered Finan McDonald wrecked the canoe of a Spokane man who dared to spear fish below the company weir. The canoe owner responded by tearing down a section of fence around Finan’s potato garden before cooler heads prevailed.

During the summer of 1822, workers at the post were busy with a major remodel of the 10-year-old buildings, including a new boathouse and defensive measures.

But the following fall, when Nicholas Garry, governor of Hudson’s Bay Company, visited Spokane House, he was not happy with the lifestyle he observed there: “The good people of Spokane District generally have shown an extraordinary predilection for European provisions without considering the enormous price it costs…. They may be said to have been eating Gold,” Garry wrote.

The next spring, after a consultation with Finan McDonald and other clerks, the governor decided to abandon the newly remodeled post and move its operations to a new location at Kettle Falls, to be called Fort Colvile. The logic was clear: The move would place the district headquarters on the Columbia’s main stem and eliminate costly horse brigades to the mouth of the Spokane; the salmon at the Kettle Falls were even more abundant than those at Spokane House; outposts in the Kootenai and Flathead country could be easily supplied. The only difficulty the governor saw in taking leave of Spokane House was that “it may give offence to the Spokan Indians who have always been staunch to the Whites.”

Before departing, the governor obtained permission from Ilum-Spokanee to carry his young son east to attend school at the Red River Colony (near modern Winnipeg, Manitoba), in order to help the transition of the Spokane people into the modern world. The youngster was baptized with the name of Spokane Garry. When the fur brigade left that spring, the lad was tucked in among the season’s fur packs, bound for eastern Canada.

By the spring of 1826, most of the trade goods and equipment had been ferried to the new Fort Colvile. The blacksmith and cook were collecting the last bits of iron from the place, right down to the door hinges. The clerk in charge of the move from Spokane commented that “the Indians much regret our going off,” but when he returned during the summer fishing season, he found most of the people working at their traditional fishing barrier — and taking in 700 or 800 salmon per day.

The abandoned Spokane House buildings were apparently bequeathed to Jaco Finlay. Over the next two years, Jaco, Teshwintichina and a variety of offspring greeted numerous visitors traveling along the trails near the post. Jaco died in spring 1828 at the age of 60. According to tribal accounts, he and his effects were buried beneath a bastion at the corner of the old stockade.

Eight years later, when a Protestant missionary stopped by the site, he reported “a very pleasant, open valley, though not extensively wide. The North-west Company had a trading post here, one bastion of which is still standing.” Apart from that single bastion, the confluence must have looked much as it had when Jaco first rode into the cluster of tule mat lodges in 1810.

NEW WAVE

When a new wave of white settlers began building the city of Spokane in the 1870s, many made the trek nine miles downstream to survey the old Spokane House site, and pioneer reminiscences and tribal oral histories about the fur trade era surfaced regularly in local newspapers. For three years beginning in 1950, archaeological explorations on the site confirmed some of that history. During the second year of research, the diggers — working on a tip from a local historian who had listened to tribal stories — uncovered a bastion on the northwest corner of the old post’s footprint. Beneath the square, the crew found a rotted coffin that contained human bones as well as a comb, a tin drinking mug, a hunting knife, part of a writing slate, three brass buttons, a pair of reading spectacles and five smoking pipes — one of them incised with the initials JF. The remains were declared to be those of Jaco Finlay, and were reinterred in 1976.

Today, a memorial brass plaque marking Jaco Finlay’s grave is surrounded by colored steel beams delineating the outlines of the posts built in 1812 by the Pacific Fur Company and later enlarged and remodeled by the North West and Hudson’s Bay Companies. The exact location of the original small trade house constructed by Jaco Finlay in the summer of 1810 has never been definitely determined.

Perhaps, however, the legacy of that first Spokane House lies not so much in its precise location as in its human impact. A large number of current citizens across the region count the men on the payrolls of the North West, Pacific Fur and Hudson’s Bay Company as their ancestors. In a very real sense, Jaco Finlay, Finan McDonald, and their Spokane House cohorts marked the beginning of the Inland Northwest that we know today.

The Spokane House Bicentennial “Living History Fur Trade Encampment” — complete with historical reenactors, flintlock shooting and a cannon salute — on Saturday-Sunday, June 19-20, from 10 am-5 pm at Spokane House Interpretive Center, Hwy. 291, Nine Mile Falls, Wash. Visit friendsofspokanehouse.com. Spokane author Jack Nisbet wrote more about David Thompson in his book Sources of the River.