On a shelf behind me is a naturally laminated cobble about the size of a door knob. It's a beauty, a sedimentary mudstone geologists call argillite, in which the "g" is pronounced as a "j."

I plucked it from a pile of loose rocks along the Spokane River bank in late August. Among its layers is a swollen varve that brings to mind the Great Red Spot of Jupiter. It's a rock that looks like it has stories to tell. And it does, on a timeline that connects to the very deep past, when multicellular life forms were just beginning to propagate.

At first glance, you wouldn't think the Spokane area and the Inland Northwest offer a compelling geologic history. There is, to be sure, an oversupply of basalt — the gnarly, black lava rock that underlies and channels the thundering waters at Spokane's signature falls. Yet compared to the Cascade volcanoes and Idaho's Sawtooth peaks, it all seems rather subdued, a burlap expanse, rimmed with pines and sage, drifting off into the bare rolling hills and flatlands of the lower Columbia Basin.

But the boring surface is a disguise. The deeper truths are sometimes in plain sight, sometimes well hidden and, for the geologically curious, they're fascinating. It's always hard to choose, but here are a half-dozen of these places I love to visit, and the stories behind them.

DEEP CREEK RAVINE

The first thing to notice about Deep Creek is what a marvelously strange place it is. For starters, the ephemeral creek is minuscule in proportion to the dramatic gorge it passes through as it approaches the Spokane River 9 miles west of Spokane. Water has been in the Deep Creek drainage for millions of years. But the ravine's grandeur and depth were naturally bulldozed by Ice Age floods inundating the Spokane area less than 20,000 years ago.

Hiking south on the creek bed below the State Park Drive parking area (see below), you're likely to notice unusual, obsidian-like pieces of glassy rock among crumbly, tan-colored knobs along the right bank. As you head downstream, look for a pair of ancient lava tubes, and then a massive cliff of "pillow" basalt and colorful palagonite — where the lava encountered an ancient lake or large stream and, in violent flashes of steam, was transformed into rich yellow, orange and even bluish colors. It's a stunning display, created 16 million years ago when the Grande Ronde lava flow — the largest of the lava flows responsible for the Columbia River basalts — arrived in the Spokane area from vents well to the south.

As you walk the creek bed you'll also notice quite a bit of rock that is not basalt, including large pieces of granite and chunks of metamorphic rock. It's all part of the debris — plucked from mountains in Canada, Idaho and Montana — deposited in the creek bed by the great floods. After a half mile — be careful crossing remnant pools of water — you'll see on the left bank a tall outcrop of whitish blue clay, streaked with orange stripes. This is the so-called Latah Formation where, in relatively calm periods between the ancient lava flows, sediment slowly collected in still water bodies. It's a good place to introduce children (and yourself) to fossil-hunting as the clay can easily be split horizontally, sometimes to reveal fossilized insects and leaves.

The towering basalt cliffs above Deep Creek are a destination spot for skilled rock climbers, so don't be surprised if you hear voices echoing above you. If you hear a high-pitched, descending series of notes, you're in the special company of one or more canyon wrens, an uncommon bird in the Spokane area.

Getting there: My favorite route to access the ravine is to drive west, cross the Spokane River at the Seven Mile Bridge, then go upgrade to State Park Drive, near the crest of the grade. Turn right there, and follow the dirt road to the parking area perched above the creek. (You'll need a Discover Pass to park here.) Just to the south — to your left, as you face the creek — you'll find a steep but manageable trail that takes you down to the creek bed. Once you reach the creek bed, turn right (north) and carefully work your way through a few narrow passages between basalt outcrops.

DISHMAN HILLS NATURAL AREA

There are two images from the Dishman Hills Natural Area that delight me. One is in plain sight. The other inflames my imagination.

I'll start with what we can see just driving east through the din of the commercial sprawl along the Sprague Avenue couplet in Spokane Valley. What emerges into view is an unexpected green tongue of pines and ancient rock reaching right down to the road. It invites you into a completely different world — a stone's throw from the urban expanse of car lots and traffic.

Such is the north gateway to the Dishman Hills Natural Area, which Spokane geologist Michael Hamilton aptly describes as "a jewel in the crown of Spokane's open spaces." The 3,200-acre natural area has its own advocacy and nonprofit management entity — the Dishman Hills Conservancy — to promote and protect the undeveloped green spaces extending southward to the Iller Creek Conservation Area on Tower Mountain's eastern flanks.

The spectacular scene requiring my imagination would have come from a day 17,000 years ago that Hamilton — an emeritus conservancy board member — describes in one of his online geology tutorials: the day the massive Purcell Trench ice dam holding back glacial Lake Missoula suddenly gave way, releasing a 65 mph flood heading south over what is now the Rathdrum Prairie.

In the 1920s, the famed scabland geologist J Harlen Bretz coined the term "the Spokane Flood" to describe this very torrent. Bretz wasn't yet sure of the cause or source of the epic flood, but he knew it had roared through Spokane before it branched out to carve a network of broad canyons and braided channels throughout the lower Columbia Basin.

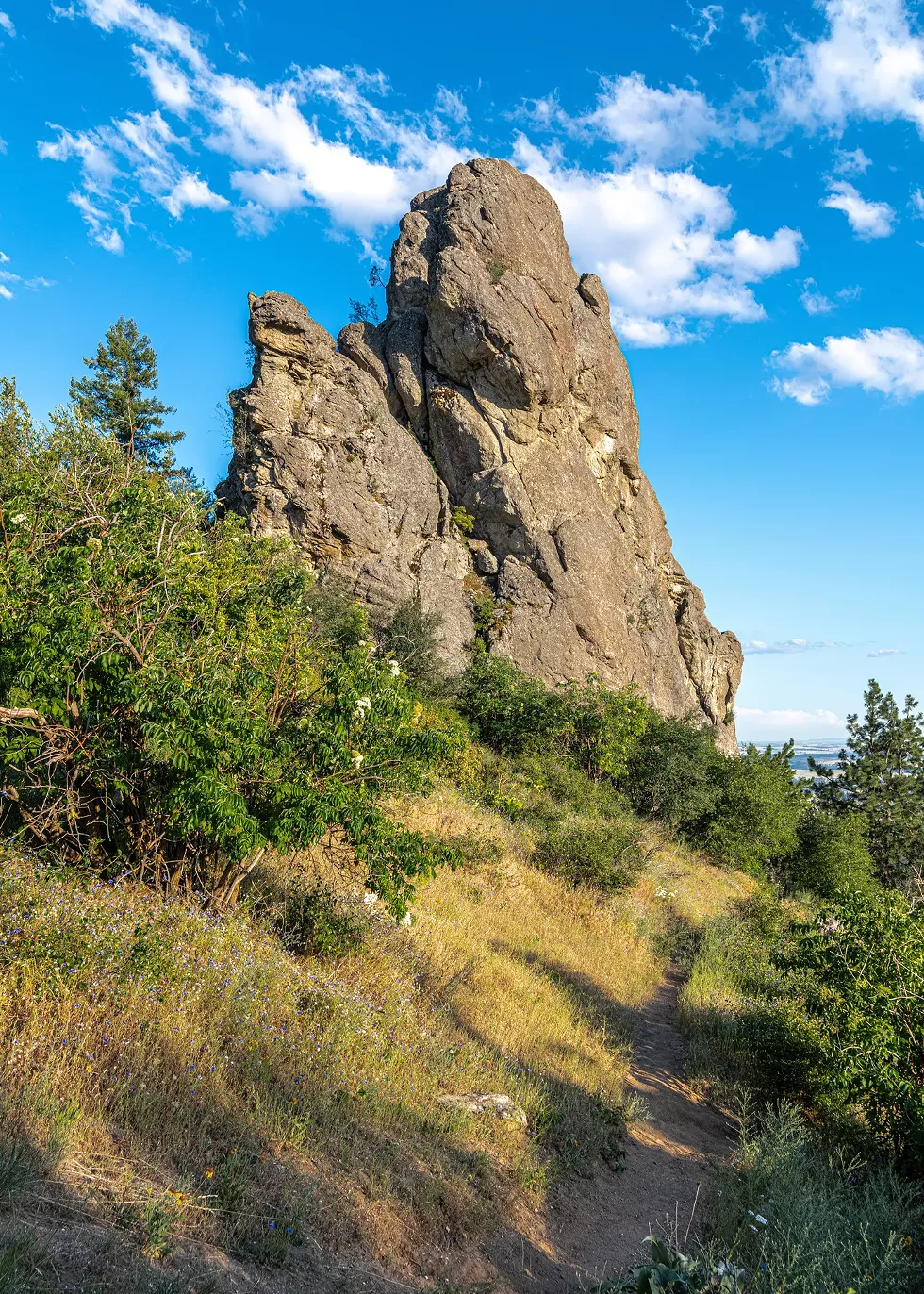

As Hamilton describes, the Dishman Hills absorbed a direct hit from the floods, and shunted the bulk of the inland tsunamis farther eastward into what is now the Spokane River gorge. The evidence from the exposed, weathered rock — much of which is well over a billion years old — is that the floodwaters also overflowed the crest of the ridge that separates the Spokane Valley from the Palouse at around 2,800 feet. The massive wave then thundered into the deep valley below and continued its liquid-riot journey, ultimately to the Pacific Ocean. Among the rocks that survived the floods are the very ancient Rocks of Sharon on the ridge just east of Tower Mountain. The highlight of the Rocks of Sharon is the aptly named Big Rock, which tops out at over 3,500 feet and is a prime destination for local rock climbers.

The view from the ridge near Big Rock is well worth the stout hike, as is the opportunity to imagine what it must have looked like when the Ice Age floods breached the crest of the surrounding hills.

Getting there: There are many entries to Dishman Hills, but the most stunning is from the south. From I-90, take the Thor/Freya streets exit and head south toward the Palouse Highway. Once on the Palouse Highway head past Valley Chapel Road toward Valleyford, and turn left on South Stevens Road. The Rocks of Sharon/Big Rock parking area is about 2 miles up the road.

ESCURE RANCH RECREATION AREA & FRENCHMAN COULEE

Not everybody would link these two sites (100 miles apart) into one story. But hear me out. It's worth the trips.

Let's start at the remote but publicly accessible Escure Ranch property along Rock Creek about 15 miles south of Rock Lake. To be sure, it's out there a ways, in one of the most remote corners of the state. Escure is a former sheep ranch, turned recreation area, that's now a favored hiking, horseback riding and camping venue far from urban anxieties and amenities.

There's quite a lot to see at Escure Ranch, including the preserved ranch buildings, a bridge over the creek and a cinematic view of the Rock Creek valley south of the parking area. But it's on a steep hillside a quarter mile north (upstream) of the parking area that you can find mounds of some most unusual rock, in colors of brick red, gray and dark blue. This is magmatic spatter—the remains of lava ejected high into the air, 15 million years ago from a vent that gave fiery birth to the Roza member of the Columbia River basalt flows. The vent is several miles long and, in its time, extended northward toward Ritzville, passing beneath what is now I-90 near the Tokio exit.

The Roza lava didn't reach Spokane to the north, but to the west and southwest it reached present-day Pasco and The Dalles. The word "reach" doesn't begin to convey what that would have looked like — a fiery, broiling, hissing brew of lava flowing steadily westward as far as any eye could see. Its most spectacular display, in present time, is at Frenchman Coulee on a high bench east of the Columbia River 7 miles north of where I-90 crosses the river at Vantage. It's a stunning arc of enormous Roza basalt columns known widely as The Feathers. Of course, Frenchman Coulee was excavated by Ice Age floodwaters millions of years after the Roza basalt was already in place. So what you're seeing is a highly improbable, toothy jaw of surviving basalt — literally one column wide, and high enough to be extremely popular for rock climbers who flock to it, by the dozen, in decent weather.

Getting there: If you're coming from Spokane, take I-90 west to Sprague and exit 245. It will link you to state Route 23, turn left and head south toward Sprague and St. John. After 8 miles, take Lamont Road on your right. Follow it through Lamont, to where the pavement becomes gravel, then turn left onto Revere Road, which climbs over Palouse uplands and then down to the Revere grain elevator. There, turn south onto Jordan-Knott Road, which crosses Rock Creek and, in 4 miles, brings you to the Escure Ranch turn-off. The turnoff will be the first road on your right after you pass the sign for Breeden Road. Drive slowly, it's bumpy.

WILLOW LAKE AUREOLE

The challenge with the deep earth story at Willow Lake is that it looks and sounds too outlandish to be true.

At first glance, what you see from a rise on I-90 appears to be a typical scabland lake just north of the freeway. The water is surrounded by dark rock that can easily be mistaken, from afar, as basalt — the familiar lava rock that outcrops in low buttes and road cuts for well over 100 miles south and west of Spokane. But the rocks at Willow Lake are not basalt. Rather, they're the gray-greenish rock of the 1.45-billion-year-old Wallace Formation.

What's stunning about the Wallace rocks, here, is that in many places they're swirled together — like chunks of pistachio in dispensed frozen yogurt — surrounded by granite and sparkling, black amphibolite. This is the natural art of what geologists call the Willow Lake aureole — a ring of transformation where subsurface molten rock (the relatively young granite) has intruded into older rock layers, in this case the Wallace Formation. Whether you're a rockhound or not, it's quite a sight.

In less spectacular form, you can expect to see rock like this in the mountains and road cuts of the Idaho panhandle and western Montana. The Wallace Formation is one of the major layers in the so-called Belt Basin. Named after the Big Belt Mountains south of Great Falls, Montana, the Belt is an enormous sedimentary basin that formed over a 90 million-year period ending approximately 1.38 billion years ago. During the uplift and folding of the northern Rockies, the Belt strata were lifted skyward from an astonishing depth of 10 miles.

You can find outcrops of Belt rock in Eastern Washington, but generally they're very close to the Idaho border. The outcrops include a huge wall on East Trent Avenue, and several outcrops near Liberty Lake. You just don't expect to see Belt rock on the plains west of Spokane. Or at least I didn't.

I visited Chad Pritchard, a geologist at Eastern Washington University in Cheney, to find out why. On two large computer screens in his cramped office, Pritchard brought up a topographic display to show me what happened. Willow Lake and Granite Lake (just southwest of Spokane) were created by powerful direct hits from the Ice Age floods.

The floodwaters overflowed what is now the Spokane River gorge and moved at freeway speed exactly down the path I-90 follows now, obliterating what used to be a ridge connecting Wrights Hill to the south and Riddle Hill to the north. In doing so, the water-hammer floods carved out the lakes, exposing the granite at Granite Lake and the earth magic of the Willow Lake aureole.

The Belt rocks at Willow Lake shed light on a deeper and fascinating question. Where's the very ancient edge of North America?

Although it's no longer news to geologists, it may surprise many that most of what is now Washington, Oregon and California was added as lumps and ribbons of terrain — generally traveling at the pace of a growing fingernail — arriving from the south and west on oceanic plates. They were essentially scraped off as the oceanic plates (like today's Juan de Fuca Plate) slid beneath the North American Plate over the past 200 million years.

But where was the continent's west coast before then?

There are three visible outcrops of Belt rock that offer a clue. The first is in the Chewelah Valley some 50 miles northeast of Spokane. The second is on an island in Bonnie Lake about 35 miles south of Spokane, where there's a 1.5 billion-year-old outcrop of metamorphic rock, also associated with the Belt Basin. With the Willow Lake aureole in the middle, the three outcrops are on a nearly straight line, slightly tilted to the southeast, spanning 80 miles. In short, it posits the boundary of the very ancient edge, at least in Washington state.

Pritchard smiles and nods as we discuss this.

"Yes," Pritchard says between chuckles, "so you can imagine seeing the waves of an ancient ocean lapping to a shoreline near Medical Lake."

Getting there: Willow Lake is easily accessible (and easy to spot) from I-90. Take the Four Lakes exit as if heading to Medical Lake. Once on the north side of the interstate, head west on Silver Lake Road. Willow Lake is on your right, and I-90 will be on your left.

SPOKANE RIVER

On a map, or from the air, it's plain to see that the river primarily gathers its water from its headwaters at Lake Coeur d'Alene. Yet, for most the year, an unseen river is vital to sustaining the flow in Spokane's signature watercourse. The geographic name for it is the Spokane Valley-Rathdrum Prairie Aquifer, and it lives and flows in what is essentially an underground coulee. It is a U-shaped trough, more than 600 feet deep in places — filled to its brim with saturated boulders and cobbles. It's where Spokanites get their drinking water.

To be sure, there is plenty of photogenic basalt attached to the river, not just the signature falls in downtown Spokane but the handsome pillars that my parents posed with, at the Bowl and Pitcher, on their honeymoon. But what most interests me are the myriad billions of cobbles, essentially all of which were delivered by the catastrophic outwash from glacial Lake Missoula at the end of the most recent ice age. The flood cobbles are not just in the river and on the shore. They're ubiquitous in Spokane but largely hidden by a thin layer of silty topsoil.

I recall driving up a hill in east Spokane a few years back in the wake of a thunderstorm. Stormwater had overflowed a ditch and spewed on to Altamont Street with such force that it had dumped a large batch of wet cobbles, glistening in the post-storm sunshine. The colors were so vivid that it looked as though someone had emptied a chest of jewelry onto the roadway. The beautiful cobbles are more noticeable in and along the river because the rushing water exposes them and helps to clean the algae off their surfaces. Which brings me back to where I started — the beautifully layered knob of argillite I picked up in late August.

Like so many other Spokane cobbles, it's all but certainly from the very ancient Belt Basin. For example, the colorful rock exposed in the heights of Montana's Glacier National Park is predominantly from the Belt Basin, lifted skyward by what geologists call the Sevier orogeny — a period of mountain building in the West ending about 50 million years ago. Think of the Lake Missoula floods as very dirty ice water, in which the lion's share of the dirt was Belt Basin rock.

I've saved the jaw-dropping part for last.

Just in the past few years there is solid and accruing evidence (radiological, chemical and paleomagnetic) that the Belt Basin formed at a time when the Inland Northwest — including the Spokane area — was docked against parts of what are now Australia and Antarctica. This would take us back into the times of ancient supercontinents Columbia and Rodinia. Thus, when the Belt Basin was gathering its countless grains from eroding mountains, it was collecting sediments from both the east and the west — not just from highlands in what is now the northern Rockies, but from highlands in Australia and eastern Antarctica as well. What this means is that Belt Basin cobbles — like the one I picked up in August — contain not just grains of long-ago mountains in Montana, but mountains from lands now on the other side of the planet.

It's quite a handful. ♦

Tim Connor is an award-winning journalist and nature photographer based in Spokane. His latest book is Beautiful Wounds.