On kennel doors, sidewalks and throughout other pet-friendly spaces, deadly viruses may be lying in wait to infect the next cat or dog that comes their way.

Physical contact isn't necessary for transmission of these viruses. The health and lifestyle of the animal often doesn't matter. That's why the American Animal Hospital Association (AAHA) classifies vaccines used to treat these viruses as the "core vaccines" for dogs and cats.

For dogs, these deadly viruses include adenovirus, distemper virus and parvovirus.

Even with veterinary care, the American Veterinary Medical Association estimates that canine parvovirus kills about 10 percent of dogs that contract the virus. The virus affects the gastrointestinal tract and may be spread through contact with other dogs, contaminated feces, environment and people.

Canine distemper virus is just as deadly. The virus attacks the respiratory, gastrointestinal and nervous systems of dogs, usually puppies, and is spread by sneezing and coughing dogs or via contaminated spaces like water bowls. The virus can be shed for months and passed on to puppies from their mother.

Canine adenovirus is a deadly infection of the liver largely spread by contaminated dogs through their urine and feces. The virus can lead to liver failure and death.

Calicivirus, herpesvirus and the feline form of canine parvovirus known as panleukopenia make up three of the core vaccinations for cats.

Panleukopenia was once a leading cause of death for cats until an effective vaccine was developed. The virus can easily kill a cat, and even with proper veterinary care, it can be more difficult to save a cat from panleukopenia than a dog with parvovirus.

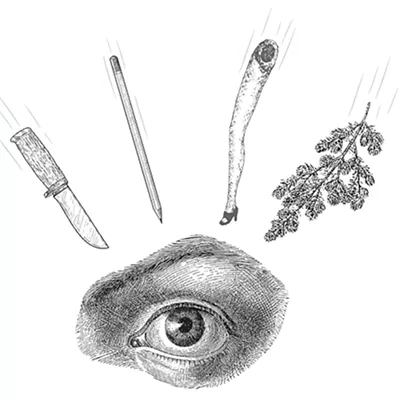

While calicivirus and herpesvirus are rarely fatal on their own, these infections may cause symptoms that lead to death. Feline herpesvirus causes severe respiratory disease and feline calicivirus is characterized by painful ulcerations in the mouth that deter a cat from eating and drinking.

Due to the prevalence of these viruses in cats and dogs, it is best for owners to fully vaccinate animals at eight, 12 and 16 weeks of age. For animals in undervaccinated regions or where feral animals may reside, an extra vaccine at 20 weeks is often recommended by AAHA, as well as boosters for each of these vaccines every one to three years.

The rabies virus, which rounds out AAHA's core vaccinations for dogs and cats, can kill an infected human, dog or cat in as little as a week.

Rabies virus can infect all mammals, including humans. It is only treatable in people with early intervention and is fatal in all other mammals. Due to the severity of the rabies virus, most states, including Washington, require all dogs, cats and ferrets to be vaccinated.

Jessica Bell is an assistant professor at WSU College of Veterinary Medicine and a small animal veterinarian in community practice at WSU's Veterinary Teaching Hospital.