Out of context, it could sound downright barbaric — drilling into a patient’s skull and electrifying tissue — but deep brain stimulation (DBS) has been a godsend for many people suffering from Parkinson’s disease. It’s been shown to ease their tremors and other motor symptoms related to the chronic brain disorder.

“It’s hope for them,” says Dr. David Greeley, founder of Northwest Neurological in Spokane, which has handled most local patients opting for DBS. “Even getting on the waiting list [for the procedure], people get better. For the first time, they’ve had an opportunity for stabilization and improvement.”

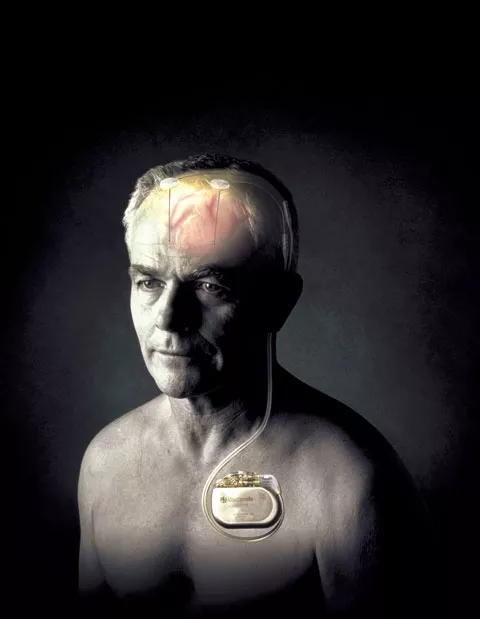

The procedure takes two operations. First, a surgeon opens a patient’s skull and snakes tiny electrodes into particular areas of the brain. A week or so later, a second surgery is needed to run wires beneath the skin from the electrodes to a pacemaker implanted near the collarbone.

When connected, the device sends low-level electric current to the part of the brain used in controlling movements. For many with Parkinson’s, it’s meant fewer tremors and less stiffness and slowness. For 74-year-old Jim Williams, who had the procedure done in March, it’s helped him stay more active. “All in all, it was very good,” he says. “It’s still good. And I’d do it again.”

After the initial surgeries, the DBS devices will need to be adjusted periodically, according to a patient’s responses, says nurse practitioner Jamie Mark, who works with Greeley at Northwest Neurological.

A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2006 found that DBS patients had a 41 percent improvement in motor skills and a 25 percent improvement in quality of life. The study concluded that DBS was notably better than conventional drug treatment. “It’s huge,” says Greeley. “People get better sleep, which means they’re more active, which means they get better sleep. It’s cyclical.”

But while Greeley and others agree DBS has demonstrated its effectiveness, it’s not entirely clear why it works. There are theories — the electric impulses seem to block the electrical signals that cause physical symptoms — but in the end, the brain and brain stimulation are still somewhat of a mystery.

“It’s the last frontier,” Greeley says of the brain. “It’s like a PC has been dropped in the world of cavemen, and we have only just learned that pushing a button makes a line.”

Still, it doesn’t work for everyone. Because it involves an invasive procedure, doctors tend to consider DBS only after medications have lost much of their effect in controlling symptoms. Good candidates for the procedure also must be strong enough for surgery.

In 1997, the Food and Drug Administration approved DBS for treatment of Parkinson’s and essential tremor, a more common disorder that causes trembling. It’s also been approved for dystonia, which can cause debilitating muscle spasms. But while it’s been around for years, it’s only now beginning to catch on, says Greeley, who estimates that nationally about 1 percent of Parkinson’s patients have undergone the procedure although 10 to 20 percent might be solid candidates for it.

Now, DBS is being studied as a treatment for all sorts of afflictions, including Tourette’s syndrome, obesity, traumatic brain injury, epilepsy, chronic headaches, depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

“If you look at the research,” Greeley says, “the potential is huge.”

DID YOU KNOW?

Parkinson’s disease affects 1 in 100 people over the age of 60, with the average age of onset being 60 years, according to the National Parkinson Foundation. An estimated 60,000 new cases are diagnosed every year in the United States.