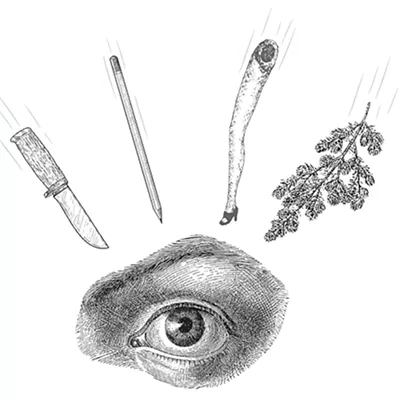

Ah, the toilet! If it is disgusting, flush it away. Dead goldfish? Flush them. Old antibiotics for that long-gone strep throat? In the commode. Unused birth control pills? Whoosh!

Those things you send down the toilet, and down all the other drains in your home, have to go somewhere — and nearly always, that somewhere is a wastewater treatment plant that filters out or neutralizes contaminants and releases the cleaned water.

University of Idaho environmental toxicologist Greg Moller says wastewater plants have done a remarkable job with natural waste. “But in the ’60s we learned ‘better living through chemistry,’” Moller says. In the years since then, new drugs, hormones and other chemical compounds have been made, ingested and excreted. “Micropollutants,” Moller calls them.

In March, the Associated Press reported that bits of these “micropollutants” have been detected in the water supplies of some major U.S. cities. “In the Hudson River,” says Moller, “trace levels of Viagra and antidepressants were found.”

Moller says scientists have found that some of those “micropollutants” harm aquatic life — fish particularly, messing with their reproductive systems. But do they harm people?

“It’s difficult to show a cause and effect,” says Jim Hudson, a senior engineer for the Washington Department of Health. “Caffeine has been found in some watersheds that are used as water sources,” but no resulting health problems have been reported.

That may be because there hasn’t been much testing for things the Environmental Protection Agency calls “PPCPs,” pharmaceuticals and personal care products. The list of PPCPs is long and diverse; it includes drugs for human use (both legal and illegal), drugs for animals, fragrances, cosmetics, vitamins and sunscreens. Municipal water systems aren’t required to look for these things.

The problem may lie in knowing where to begin. “There are tens of thousands of synthetic organic compounds. Which do you test for?” asks Dr. Remy Newcombe, the chief technology office at Blue Water Technologies in Coeur d’Alene. “It wasn’t until recently that we even had the tests to detect some of these things, and they tend to be pretty expensive.”

For Greg Moller, a good place to start would be banning triclosan, a compound used in liquid antibiotic soaps. “It’s really unnecessary,” he says. “It cleans your hands no better than soap and water. And we’ve documented the damage it does to fish.” Some of the water purveyors surveyed in the AP investigation were cautious about disseminating information about “micropollutants” in their water supplies, saying they worried the public would panic.

“It bothers people to hear that there are trace chemicals in their water,” says Moller. “There will be calls for more monitoring. The problem is there is no clear and present danger. Where does the risk lie? What can we do to mitigate the risk?”

Two Inland Northwest projects are working to reduce the risk by diverting pharmaceuticals from public water supplies. Group Health, the Department of Ecology and several environmental groups encourage people to bring their unused, unwanted drugs to Group Health clinics in Washington.

“We designed a secure box — like a mailbox — with a chute where people could drop their old drugs into a five-gallon bucket inside,” says pharmacist Shirley Reitz, Group Health’s assistant director of pharmacy clinical services. “We started in seven clinics and now we have the boxes in 25 of our Washington clinics. We’ve collected about 7,000 pounds of pills of all colors, shapes and sizes, sometimes in very large bags.” Group Health also has plans to put boxes in its Coeur d’Alene facility, once Idaho state hazardous waste rules allow it.

In the second project, WSU pharmacy students and the Spokane County Solid Waste System are distributing brochures to pharmacists, showing the proper way to dispose of unwanted drugs. The target audience isn’t the pharmacists — it’s the customers who ask about drug disposal.

“We want to discourage people from flushing drugs down the toilet,” says WSU pharmacotherapy professor Bill Fassett. If people don’t want to take their old drugs to one of the Group Health drop boxes, they can take them to the hazardous materials area at the Waste-to-Energy plant. “The only good way to get rid of them is to incinerate them,” says Fassett, “and we’re in a unique place here where we can do that.”